Introduction

- Histoplasmosis is a systemic fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can exist as a mold in the environment and as a yeast in human tissues.

- The infection primarily affects the lungs but can disseminate to other organs, including the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

- Histoplasma capsulatum is commonly found in areas with soil contaminated by bird or bat droppings, especially in regions of the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

- People acquire the infection by inhaling airborne conidia (spores) released from the environment.

- Although the infection is often asymptomatic or mild in healthy individuals, it can cause severe, life-threatening disease in individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or other immunosuppressive conditions.

Etiology

The causative agent of histoplasmosis is Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus, meaning it can adopt two different forms depending on environmental conditions:

- Mold form: H. capsulatum exists as a mold in the environment. It forms characteristic conidia (spores) released into the air when disturbed, especially in environments contaminated with bat or bird droppings. The conidia are inhaled by humans or animals, initiating infection.

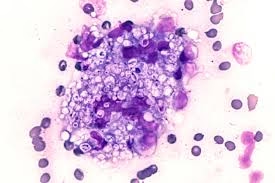

- Yeast form: After inhalation of the conidia, the fungus transforms into its yeast form at body temperature (37°C) inside the host. This yeast form is the pathogenic form of the organism. It is characterized by small, oval, intracellular yeast cells that reside within macrophages, and it causes tissue damage and inflammation.

Specimens

Various clinical specimens can be collected for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, depending on the nature and severity of the infection:

- Respiratory Specimens: The lungs are the primary site of infection, and respiratory specimens such as sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid are commonly collected for testing. These samples help identify the presence of H. capsulatum.

- Biopsy Samples: In cases of disseminated histoplasmosis or severe disease, biopsy specimens from affected organs such as the bone marrow, liver, spleen, or lymph nodes may be obtained. These specimens can provide definitive evidence of infection.

- Blood Samples: Blood cultures may be taken to detect systemic infection, especially in immunocompromised patients, although H. capsulatum is often difficult to isolate from blood. Serology can be used to detect antibodies or antigens.

- Urine: Histoplasma antigen detection can be performed on urine samples, especially in cases of disseminated histoplasmosis, where antigen levels may be elevated.

Direct Microscopic Examination

Direct microscopic examination plays an important role in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis:

- KOH (Potassium Hydroxide) Preparation: Respiratory specimens, such as sputum or bronchial lavage fluid, can be prepared with a KOH solution to dissolve cellular material, making it easier to detect fungal elements. In the yeast form, H. capsulatum appears as small, oval, intracellular organisms within macrophages.

- Histopathology: A biopsy specimen can be processed for histopathological examination, often using stains such as Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS), Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS), or Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). H. capsulatum appears as small, oval yeasts, often inside macrophages or other phagocytic cells. Granulomatous inflammation may also be observed.

- Lactophenol Cotton Blue Staining: This stain is used to observe the mold form of H. capsulatum when cultured from environmental specimens. It reveals the characteristic conidia and hyphal structure of the fungus.

- India Ink Staining: While more commonly used for diagnosing cryptococcosis, India ink preparation may sometimes be used with other methods to highlight fungal structures in clinical specimens. However, this is not a primary diagnostic method for histoplasmosis.

Culture and Identification

Culture is one of the most definitive methods for identifying Histoplasma capsulatum. Key points for culturing and identifying the organism include:

- Culture Media: H. capsulatum grows well on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar, which support fungal growth. The organism grows relatively slowly and may take 1-3 weeks to form visible colonies. The mycological culture media can isolate and identify the fungus in clinical specimens, such as sputum or biopsy tissue.

- Incubation Conditions: Cultures are incubated at two different temperatures to promote the growth of both the mold and yeast forms. At room temperature (25-30°C), H. capsulatum grows in its mold form, producing characteristic white to light brown colonies with a powdery texture. At body temperature (37°C), it transforms into the yeast form, which appears as moist, cream-colored colonies.

- Colony Morphology: In the mold phase, H. capsulatum forms small, white to tan colonies with a velvety texture, which may become darker. The conidia are produced on short conidiophores, appearing as small, round, to oval structures under the microscope.

- Microscopic Examination: The yeast form, which is the pathogenic form, appears as small, oval, intracellular yeasts, often residing inside macrophages. The yeast cells are usually 2-5 micrometers in size, and their oval shape is one of the key diagnostic features.

- Biochemical Identification: In some cases, biochemical tests, such as the urease test or carbohydrate assimilation tests, can be used for species identification. However, Histoplasma capsulatum is typically identified based on its morphology and growth characteristics.

- Molecular Methods: Molecular techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or DNA sequencing, can identify H. capsulatum more accurately and quickly. These methods are particularly useful in complex cases or when other methods fail.

Other Laboratory Tests

- Antigen Detection: Antigen detection tests, such as enzyme immunoassays (EIA), are available for detecting H. capsulatum antigen in urine, serum, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. These tests are highly sensitive, especially in cases of disseminated histoplasmosis, and can provide rapid results. Detection of the Histoplasma antigen is useful in diagnosing active infection in immunocompromised patients.

- Serology: Serological tests (such as immunodiffusion or complement fixation tests) can detect antibodies against H. capsulatum in serum, especially in patients with chronic or past infections. However, serology is not useful for diagnosing acute infections and may be negative in immunocompromised individuals.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): PCR-based tests have been developed to detect Histoplasma DNA in clinical specimens. These tests are useful for diagnosing histoplasmosis when culture and microscopy are inconclusive, especially in tissue biopsy specimens.

Pathogenesis

Histoplasmosis primarily affects the lungs upon inhalation of H. capsulatum conidia. The pathogenesis of the disease involves the following steps:

- Inhalation of Conidia: Histoplasma capsulatum conidia are inhaled into the lungs, phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. These conidia then transform into the yeast form of the fungus inside the macrophages, allowing it to survive and replicate within the host.

- Granulomatous Inflammation: In response to the infection, the immune system forms granulomas around the yeast cells, attempting to contain the infection. This process often leads to a self-limited infection or a latent form that does not cause symptoms in healthy individuals.

- Dissemination: In immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, or patients on immunosuppressive therapy, H. capsulatum can disseminate from the lungs to other organs, including the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and central nervous system (CNS). Disseminated histoplasmosis can cause severe, life-threatening diseases, including fever, weight loss, anemia, and organ failure.

- Chronic and Subacute Forms: In some individuals, particularly those with prior lung conditions, histoplasmosis can cause chronic pulmonary disease. This can present as cavitary lesions, similar to tuberculosis, especially in older adults or those with compromised lung function.

Treatment of Histoplasmosis

Treatment for histoplasmosis depends on the severity of the disease and the immune status of the patient:

- Mild to Moderate Pulmonary Histoplasmosis: In otherwise healthy individuals with mild symptoms, histoplasmosis may resolve without treatment. However, if treatment is required, itraconazole is the drug of choice. This antifungal inhibits ergosterol synthesis, impairing fungal cell membrane integrity. Treatment typically lasts for 6-12 weeks.

- Severe or Disseminated Histoplasmosis: In severe or disseminated histoplasmosis cases, amphotericin B (either in liposomal or deoxycholate form) is often administered intravenously, particularly in life-threatening cases. After stabilization, treatment may be switched to oral itraconazole for long-term therapy.

- Chronic Pulmonary Histoplasmosis: Chronic or cavitary histoplasmosis often requires prolonged treatment with itraconazole, sometimes for 12-24 months. In some cases, surgery may be necessary to remove large, cavitary lung lesions.

- Immunocompromised Patients: For patients with compromised immune systems (such as those with HIV/AIDS), antifungal therapy is typically extended and combined with immune restoration, such as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for HIV-infected patients.

- Prevention: Prevention of histoplasmosis involves avoiding exposure to environments likely to contain H. capsulatum spores, particularly bat or bird droppings. Workers in high-risk occupations (such as construction workers, farmers, or spelunkers) should wear respiratory protective equipment, such as N95 masks when working in areas with contaminated dust.