Introduction

- Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic nematode (roundworm) that causes strongyloidiasis.

- It is unique among intestinal helminths because it can complete its life cycle inside and outside the human host.

- This parasitic worm can live in the intestines and sometimes migrate to other organs, leading to severe health problems, especially in individuals with compromised immune systems.

- The infection can remain asymptomatic in many cases, but it can become life-threatening in immunocompromised individuals.

Geographical Distribution

Strongyloides stercoralis is found globally but is more prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in areas with poor sanitation and hygiene practices. The highest rates of infection are reported in:

-

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Southeast Asia

- South America

- Central America

- Southern United States

The prevalence is particularly high in rural or low-income urban areas where people may have limited access to sanitation facilities and clean drinking water. The infection can also be found in individuals who travel to or live in endemic areas.

Habitat

Strongyloides stercoralis primarily resides in the small intestine of humans, where it grows into its adult form. The larvae penetrate the skin or are ingested, depending on the route of infection. In the intestines, the adult worms live and lay eggs, which hatch into larvae that are either passed in the stool or reinfect the host.

-

- Adults: The adult worms live embedded in the intestinal wall, feeding on the host’s blood and mucosal cells.

- Larvae: Larvae are present in the environment, either in feces, where they can infect other humans or inside the host, where they can develop into adults or migrate to other organs.

Morphology

- Adults:

- Female Strongyloides worms are small, measuring around 2-3 mm long, while males are smaller.

- The body is cylindrical and transparent.

- The anterior end of the adult worm is pointed, and it has a characteristic buccal cavity for feeding.

- The female is viviparous, meaning she produces larvae rather than eggs.

- Larvae:

- There are two distinct types of larvae in the life cycle: rhabditiform larvae and filariform larvae.

- Rhabditiform larvae are non-infective, present in stool, and can either develop into more larvae or become filariform larvae.

- Filariform larvae are in the infective stage, which can penetrate the skin or be ingested.

- The larvae are slender, transparent, and approximately 300-600 micrometers long.

- There are two distinct types of larvae in the life cycle: rhabditiform larvae and filariform larvae.

Life Cycle

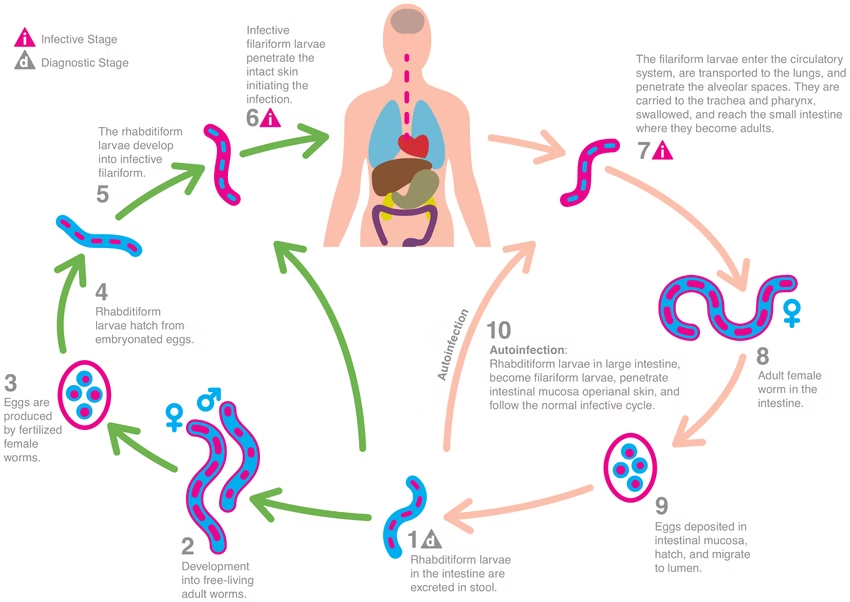

The life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis is complex and can be divided into both direct and indirect stages:

-

- Free-Living Cycle (External):

- Eggs are passed in the feces of an infected person.

- The eggs hatch into rhabditiform larvae, which develop into either filariform larvae (infective stage) or continue as rhabditiform larvae that can reproduce and continue the free-living cycle in the soil.

- The filariform larvae (infective form) remain in the soil or environment and can infect new hosts.

- Parasitic Cycle (Internal):

- The filariform larvae penetrate the host’s skin, typically through the feet, entering the bloodstream.

- The larvae migrate through the circulatory system to the lungs, enter the alveoli, ascend the bronchi, and are eventually swallowed.

- Once swallowed, the larvae reach the small intestine, where they mature into adult females.

- The adult females lay eggs that hatch into rhabditiform larvae, passed in the stool.

- These larvae can either continue the life cycle outside the host or auto-infect the host by migrating from the intestines back into the bloodstream (autoinfection) or penetrating the intestinal lining.

- Autoinfection:

- In cases of autoinfection, rhabditiform larvae in the intestine can mature into filariform larvae, which re-enter the bloodstream and migrate to other organs, causing chronic or severe infections.

- Free-Living Cycle (External):

The life cycle of Strongyloides can be completed in as little as 2-4 weeks.

Mode of Transmission

Strongyloides stercoralis is transmitted in a fecal-oral manner and through skin penetration:

-

- Skin Penetration: The most common transmission mode occurs when filariform larvae in the soil penetrate the skin, often through the feet. The larvae enter the bloodstream and eventually migrate to the lungs, where they are swallowed and travel to the small intestine.

- Ingestion: In some cases, the filariform larvae can also be ingested through contaminated water or food, where they travel to the small intestine.

- Autoinfection: The larvae can also complete the cycle inside the same host through autoinfection, where larvae hatch in the intestines and migrate back into the bloodstream.

Incubation Time

The incubation period for Strongyloides infection can vary depending on the mode of transmission:

-

- After skin penetration, the larvae can migrate through the body and mature into adults in 3-4 weeks.

- Autoinfection can result in chronic infection, with larvae potentially remaining in the host for months or even years.

The clinical symptoms usually appear within 4-6 weeks after infection.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Strongyloides stercoralis is primarily associated with its migration and reproduction inside the host:

-

- Intestinal Damage: Adult female worms living in the small intestine can cause mechanical injury to the intestinal mucosa as they feed, potentially leading to symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, or malabsorption.

- Pulmonary Symptoms: As the larvae migrate through the lungs, they may cause Löffler’s syndrome, which includes symptoms such as cough, fever, and eosinophilia (elevated levels of eosinophils in the blood).

- Auto-Infection and Chronic Infections: In immunocompromised individuals (e.g., those with HIV/AIDS, leukemia, or transplant recipients), the infection may lead to hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis, where the larvae can spread to multiple organs, including the liver, lungs, and central nervous system. This can result in life-threatening conditions, including septic shock.

- Eosinophilia: The infection can also cause a marked increase in eosinophil count, particularly during the larval migration.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection can be made using several methods:

-

- Stool Examination: The most common diagnostic method is a microscopic examination of stool samples for rhabditiform larvae. These larvae are characteristic and can be identified with proper staining techniques.

- Serology: Serological tests like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can detect antibodies or antigens associated with Strongyloides.

- Sputum Examination: Sputum samples can be examined for larvae if pulmonary symptoms are present.

- Biopsy: In severe cases, biopsy specimens from affected tissues (e.g., the intestine or lungs) may be examined to detect adult worms or larvae.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Blood tests often show eosinophilia, particularly during the larval migration.

Treatment

Treatment for Strongyloides infection involves the use of antihelminthic medications. The most common treatments include:

-

- Ivermectin: The drug of choice for treating Strongyloides stercoralis is ivermectin, which is highly effective at eradicating larvae and adult worms. It paralyzes the worms, allowing the body to expel them.

- Albendazole: This is an alternative to ivermectin and is effective against Strongyloides. It interferes with the worms’ ability to absorb glucose, leading to their death.

- Thiabendazole: Thiabendazole is another antihelminthic agent that can treat Strongyloides, though it is less commonly used today due to side effects.

- Corticosteroids: In cases of severe hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis, corticosteroids may reduce inflammation. However, caution is required since they can exacerbate the infection by suppressing the immune system.

Prevention

To prevent Strongyloides infection, several key measures can be taken:

-

- Improved Sanitation: Access to clean water, proper sewage disposal, and improved hygiene can significantly reduce the transmission of Strongyloides.

- Use of Footwear: Wearing shoes, especially in endemic areas, can help prevent larvae from penetrating the skin.

- Health Education: Public health campaigns can promote hygiene practices, including handwashing and proper waste disposal, to reduce the risk of infection.

- Deworming Programs: In endemic areas, mass deworming programs using ivermectin or albendazole can reduce the burden of Strongyloides infections.