Introduction

Enzymes are biological catalysts—usually proteins—that speed up chemical reactions in living organisms without being consumed in the process.

Definition:

“Enzymes are biological macromolecules (mostly proteins) that act as catalysts to speed up specific biochemical reactions by lowering the activation energy, without being altered in the process.”

Characteristics of Enzymes:

-

Highly specific: Act on a specific substrate to produce a specific product.

-

Very efficient: Can accelerate reactions millions of times faster than uncatalyzed reactions.

-

Reusable: Not used up in the reaction—can be used repeatedly.

-

Sensitive to conditions: Function best at an optimal temperature and pH.

-

Lower activation energy: Allow reactions to occur more easily by reducing the energy barrier.

Importance of Enzymes:

| Function | Example |

|---|---|

| Digestion | Amylase, pepsin, lipase |

| Energy production | ATP synthase |

| DNA replication & repair | DNA polymerase, ligase |

| Detoxification | Catalase (breaks down H₂O₂) |

| Metabolism | Enzymes in glycolysis, TCA cycle |

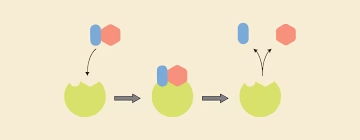

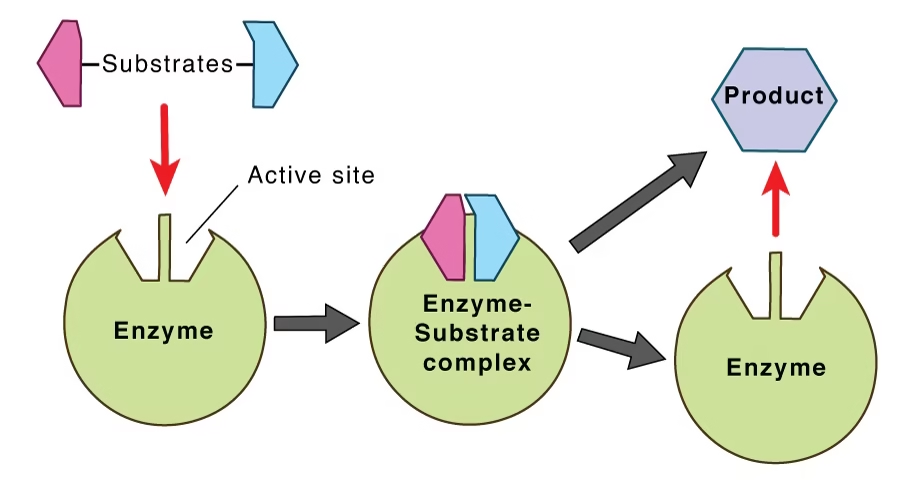

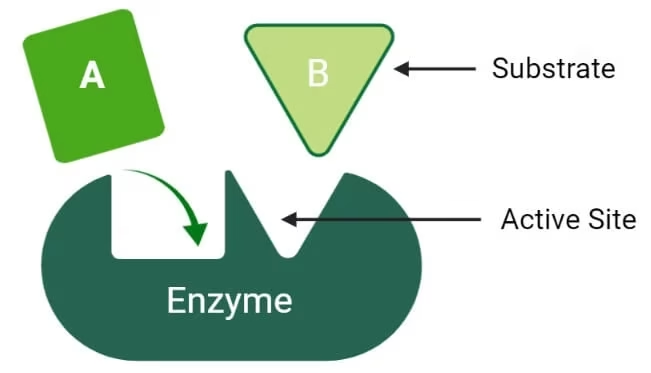

Enzyme action

Substrate: The substance on which the enzyme acts.

Product: The enzyme will convert S into the product.

E + S → ES → E + P

-

E = Enzyme

-

S = Substrate

-

ES = Enzyme–Substrate complex

-

P = Product

Enzyme is Regenerated.

Properties of enzymes

-

Biological Catalysts: Enzymes are natural catalysts that speed up biochemical reactions without being consumed.

-

Specificity: Each enzyme acts on a specific substrate or group of substrates (e.g., sucrase acts only on sucrose).

-

Efficiency: Enzymes accelerate reactions millions of times faster than uncatalyzed reactions.

-

Regeneration: Enzymes are not permanently altered in reactions; they can be used repeatedly.

-

Optimal Conditions: Enzymes function best under specific pH and temperature ranges.

-

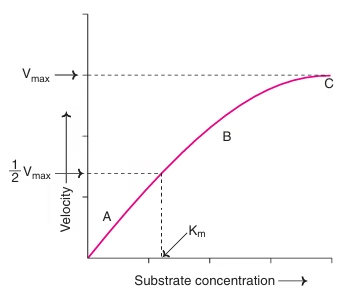

Saturation: At high substrate concentrations, enzyme activity reaches a maximum rate (Vmax).

-

Reversibility: Many enzyme-catalyzed reactions are reversible depending on substrate and product concentration.

-

Sensitivity: Enzyme activity can be affected by inhibitors, activators, and environmental changes.

-

Protein Nature: Most enzymes are proteins (some RNA molecules called ribozymes also have catalytic activity).

-

Catalytic Power: Even small amounts of enzyme can catalyze large amounts of substrate efficiently.

History of the enzyme

- Berzelius (1836) – catalysis

- Kuhne (1878) – word ‘enzyme’

- Buchner (1883) – zymase

- James Sumner (1926) – urease

- Haldane (1930) – book ‘Enzymes’

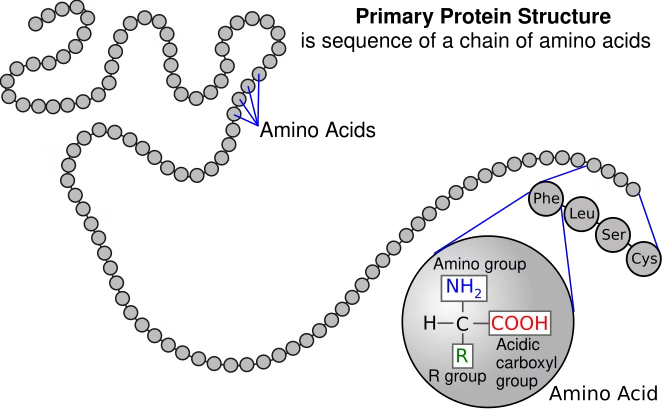

Chemical Nature of Enzymes

-

Enzymes are primarily proteins.

They are made up of long chains of amino acids folded into specific 3D shapes that determine their function. -

Some enzymes are purely proteins, e.g., urease, pepsin, amylase.

-

Some enzymes require a non-protein part to be active:

-

Cofactors (inorganic ions like Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Fe²⁺)

-

Coenzymes (organic molecules like NAD⁺, FAD, derived from vitamins)

-

-

The active site of the enzyme is the specific region where the substrate binds and the reaction occurs.

-

Ribozymes are an exception —

→ Certain RNA molecules can act as enzymes (e.g., in RNA splicing).

→ Discovered in the 1980s, they show not all enzymes are proteins.

Structure of Enzyme

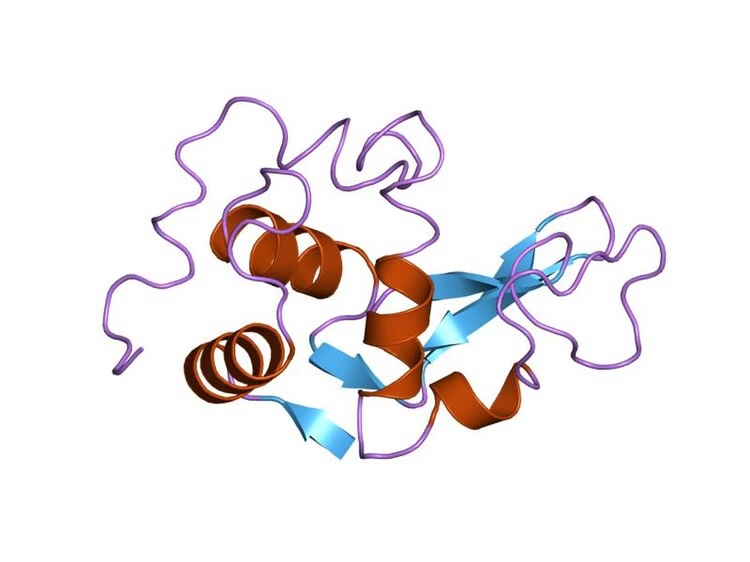

Enzymes have a complex, three-dimensional (3D) structure that is essential for their function. Here’s a breakdown:

1. Primary Structure

-

Linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain.

-

Held together by peptide bonds.

-

Determines the higher-level folding and function of the enzyme.

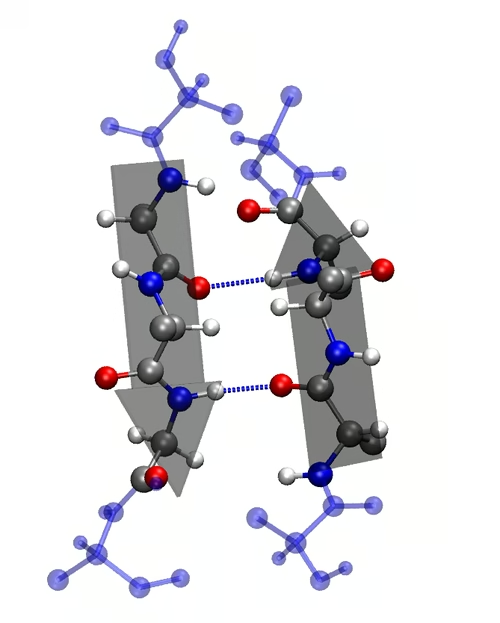

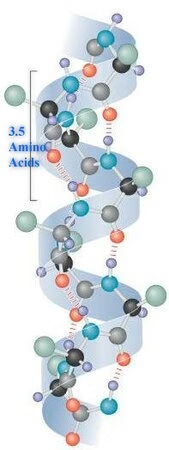

2. Secondary Structure

-

Local folding into α-helices and β-pleated sheets.

-

Stabilized by hydrogen bonds.

-

Provides initial folding patterns.

3. Tertiary Structure

-

3D folding of the entire polypeptide chain.

-

Forms a specific shape necessary for enzyme function.

-

Stabilized by:

-

Hydrogen bonds

-

Ionic bonds

-

Disulfide bridges

-

Hydrophobic interactions

-

This level of structure forms the active site, where the substrate binds.

4. Quaternary Structure (only in some enzymes)

-

Involves two or more polypeptide chains (subunits) coming together.

-

Example: Lactate dehydrogenase or Hemoglobin (though not an enzyme).

Non-Protein Moiety of Enzymes

Some enzymes require a non-protein part to be functional. This non-protein moiety contributes to the enzyme’s catalytic activity.

Types of Non-Protein Moieties:

1. Cofactor

-

Inorganic ions (metal ions)

-

Help in stabilizing the enzyme or participating in the reaction

-

Examples:

-

Mg²⁺ – needed by DNA polymerase

-

Zn²⁺ – used in carbonic anhydrase

-

Fe²⁺ / Fe³⁺ – in cytochromes

-

2. Coenzyme

-

Organic molecules (often derived from vitamins)

-

Act as transient carriers of specific atoms or functional groups

-

Loosely bound to the enzyme

-

Examples:

-

NAD⁺ (from niacin) – carries electrons

-

FAD (from riboflavin) – electron carrier

-

Coenzyme A (from pantothenic acid) – carries acyl groups

-

3. Prosthetic Group

-

A tightly or covalently bound non-protein component

-

Permanently attached to the enzyme

-

Example:

-

Heme group in peroxidase and cytochromes

-

Biotin in carboxylases

-

| Term | Nature | Binding | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cofactor | Inorganic | Loosely bound | Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺ |

| Coenzyme | Organic | Loosely bound | NAD⁺, FAD |

| Prosthetic group | Organic/Inorganic | Tightly/covalently bound | Heme, Biotin |

Classification of Coenzymes

1. Hydrogen (Electron) Transfer Coenzymes

-

Involved in oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions

-

Derived from vitamin B-complex

| Coenzyme | Derived From | Function |

|---|---|---|

| NAD⁺ / NADP⁺ | Niacin (B₃) | Transfers electrons (H⁺/e⁻) |

| FAD / FMN | Riboflavin (B₂) | Electron transfer |

| Lipoic acid | Synthesized in body | Transfers hydrogen and acyl groups |

2. Group Transfer Coenzymes

-

Transfer of functional groups (like acyl, amino, methyl, etc.)

| Coenzyme | Derived From | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Coenzyme A (CoA) | Pantothenic acid (B₅) | Transfers acyl groups |

| Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) | Thiamine (B₁) | Transfers aldehyde groups |

| Biotin | Biotin (B₇) | Transfers CO₂ (carboxylation) |

| Tetrahydrofolate (THF) | Folic acid (B₉) | Transfers 1-carbon units |

| Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) | Pyridoxine (B₆) | Transfers amino groups |

3. Isomerization and Rearrangement Coenzymes

| Coenzyme | Derived From | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B₁₂ (Cobalamin) | Vitamin B₁₂ | Rearrangement of atoms within molecules (methyl group transfer) |

Other Coenzymes (Special Roles)

-

UDP-glucose – In carbohydrate metabolism (glycogen synthesis)

-

SAM (S-adenosyl methionine) – Transfers methyl groups

Location of Enzyme Action

Enzymes can act inside or outside of cells, depending on their function. Based on this, their location of action is classified into:

1. Intracellular Enzymes

-

Function within the cell where they are produced.

-

Involved in metabolism, DNA replication, protein synthesis, etc.

Examples:

| Enzyme | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA polymerase | Nucleus | DNA replication |

| Hexokinase | Cytoplasm | Glycolysis (glucose → G6P) |

| ATP synthase | Mitochondria (inner membrane) | ATP production |

| Ribozymes | Nucleus/cytoplasm | RNA processing |

2. Extracellular Enzymes

-

Secreted outside the cell to function in the external environment.

-

Common in digestion, immunity, and microbial activity.

Examples:

| Enzyme | Source (organism) | Action Site | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | Salivary glands, pancreas | Mouth / small intestine | Starch → Maltose |

| Pepsin | Stomach (gastric glands) | Stomach | Proteins → Peptides |

| Trypsin | Pancreas | Small intestine | Proteins → Peptides |

| Cellulase | Microbes (e.g., fungi) | Outside microbial cell | Cellulose breakdown |

Classification of Enzymes

Enzymes are classified by the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) into six major classes based on the type of reaction they catalyze.

Each enzyme is assigned an EC (Enzyme Commission) number: EC X.X.X.X, where the first number indicates the class.

By Reaction Type:

1. Oxidoreductases (EC 1)

-

-

-

Catalyze oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions

-

Transfer of electrons or hydrogen atoms

-

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

-

Dehydrogenase

-

Oxidase

-

Catalase

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

-

-

2. Transferases (EC 2)

-

-

-

Transfer of a functional group (e.g., methyl, amino, phosphate) from one molecule to another

-

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

-

Transaminase – transfers amino group

-

Kinase – transfers phosphate (e.g., hexokinase)

-

Methyltransferase

-

-

3. Hydrolases (EC 3)

-

-

-

Catalyze hydrolysis (breaking bonds using water)

-

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

-

Amylase – starch → maltose

-

Protease/Pepsin – proteins → peptides

-

Lipase – fats → fatty acids + glycerol

-

-

4. Lyases (EC 4)

-

-

-

Break bonds without water or oxidation, often forming double bonds or rings

-

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

-

Decarboxylase – removes CO₂

-

Aldolase – in glycolysis

-

Fumarase – in the TCA cycle

-

-

5. Isomerases (EC 5)

-

-

-

Rearrangement of atoms within a molecule (isomerization)

-

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

-

Phosphoglucose isomerase – glucose-6-phosphate ⇌ fructose-6-phosphate

- Racemase – converts D- to L- forms

- Mutase

-

-

6. Ligases (EC 6) (also called synthetases)

-

-

- Join two molecules together using energy from ATP

-

🔸 Examples:

-

-

- DNA ligase – joins DNA fragments

- Acetyl-CoA synthetase – joins acetate + CoA

- Glutamine synthetase

-

By Cofactor Requirement:

-

- Apoenzymes: The inactive form of the enzyme without its cofactor.

- Holoenzymes: The active form of the enzyme that includes the apoenzyme and its necessary cofactors.

- Coenzymes: Organic molecules that assist enzymes, often derived from vitamins (e.g., NAD+, FAD).

- Metal Ions: Inorganic ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺) that can be crucial for the catalytic activity of certain enzymes.

By Source:

-

- Extracellular Enzymes: Enzymes that operate outside cells, such as digestive enzymes (e.g., amylase, lipase).

- Intracellular Enzymes: Enzymes that function within cells, involved in metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolytic enzymes).

Factors Affecting Enzyme Activity

Enzyme activity can be influenced by various internal and external factors that affect the rate at which enzymes catalyze reactions.

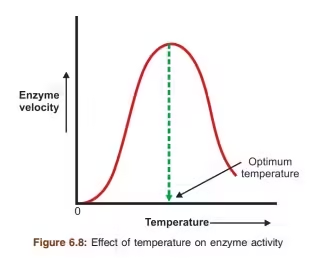

1. Temperature

-

Enzyme activity increases with temperature up to an optimum point (usually ~37°C in humans).

-

Beyond the optimum, high temperatures denature the enzyme by disrupting its 3D structure.

🔸 Graph: Bell-shaped curve

🔸 Example: Human enzymes work best at 37°C; thermophilic bacteria enzymes function at much higher temps.

2. pH (Hydrogen ion concentration)

-

Each enzyme has an optimal pH range.

-

Too acidic or too basic conditions can denature the enzyme or alter the charge of the active site.

🔸 Examples:

-

Pepsin (stomach): pH ~2

-

Trypsin (small intestine): pH ~8

-

Amylase (saliva): pH ~6.7–7.0

3. Substrate Concentration

-

At low substrate levels, the reaction rate increases as substrate increases.

-

At high substrate levels, the rate plateaus (enzyme becomes saturated).

🔸 Related to Michaelis-Menten kinetics

🔸 Maximum rate = Vmax

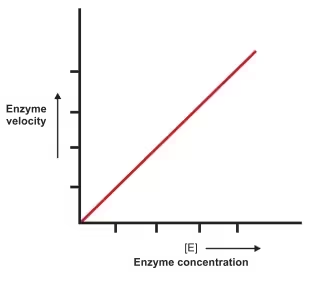

4. Enzyme Concentration

-

As enzyme concentration increases, reaction rate increases linearly, as long as substrate is not limiting.

5. Inhibitors

Chemicals that reduce enzyme activity.

Types:

| Type | Effect | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Competes with substrate for active site | Malonate inhibits succinate dehydrogenase |

| Non-competitive | Binds elsewhere; alters active site | Heavy metals like Pb²⁺ or Hg²⁺ |

| Uncompetitive | Binds only to enzyme-substrate complex | Less common |

6. Cofactors and Coenzymes

-

Some enzymes need non-protein helpers to be active.

-

Without them, the enzyme is inactive.

🔸 Examples:

-

Mg²⁺ for DNA polymerase

-

NAD⁺, FAD (coenzymes)

7. Product Concentration

-

A high concentration of product may slow down the reaction due to feedback inhibition or an equilibrium shift.

8. Time

- Under optimum conditions of pH and temperature, the time required for an enzyme reaction is less.

- The time required for the completion of an enzyme reaction increases with changes in temperature and pH from its optimum.

Isoenzymes

Isoenzymes, also known as isozymes, are different forms of an enzyme that catalyze the same reaction but may have different physical and chemical properties, regulatory mechanisms, and tissue distributions. Here’s a detailed overview of isoenzymes, including their characteristics, examples, and clinical significance.

Characteristics of Isoenzymes

- Structural Differences: Isoenzymes may differ in their amino acid sequences, leading to variations in their three-dimensional structures. This can affect their kinetic properties, such as substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency.

- Tissue Specificity: Different isoenzymes are often found in specific tissues or cell types, reflecting their unique roles in metabolic pathways. For example, some isoenzymes may be more active in the heart, while others are predominant in the liver.

- Regulatory Mechanisms: Isoenzymes can respond differently to inhibitors and activators, allowing for fine-tuning of metabolic processes in various tissues.

- Variable Stability: Isoenzymes may exhibit different stabilities under varying physiological conditions (e.g., pH, temperature), which can influence their activity in different environments.

Examples of Isoenzymes

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH):

- Isoenzymes: LDH has five isoforms (LDH1 to LDH5), composed of combinations of two subunits (M and H).

- Distribution:

- LDH1: Predominant in the heart (H type).

- LDH5: Predominant in skeletal muscle and liver (M type).

- Clinical Significance: Elevated LDH levels can indicate tissue damage or hemolysis, and the specific isoform pattern can help identify the source of damage.

- Creatine Kinase (CK):

- Isoenzymes: CK has three isoforms: CK-MM (muscle), CK-MB (heart), and CK-BB (brain).

- Clinical Significance:

- CK-MM: Elevated in muscle injuries.

- CK-MB: Used as a biomarker for myocardial infarction.

- CK-BB: Associated with brain and smooth muscle injuries.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP):

- Isoenzymes: ALP exists in several isoforms, primarily derived from the liver, bone, kidney, and placenta.

- Clinical Significance: Elevated ALP levels can indicate liver disease (biliary obstruction) or bone disorders (Paget’s disease).

- Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH):

- Isoenzymes: Exists in mitochondrial and cytosolic forms.

- Clinical Significance: Used to assess liver function and can be elevated in liver diseases.

Diagnostic importance of enzymes

- Markers for Organ Function

Certain enzymes are specific to particular organs and can indicate the health or damage of those organs when their levels are altered in the bloodstream.

- Liver Enzymes:

- Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT): Elevated levels can indicate liver damage, such as hepatitis or cirrhosis.

- Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST): High levels may indicate liver injury but can also be elevated in heart diseases.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP): Increased levels can suggest liver disease or bone disorders.

- Cardiac Enzymes:

- Creatine Kinase (CK): The CK-MB isoenzyme is used to diagnose myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Troponin: While not an enzyme per se, troponin levels are measured to assess cardiac muscle damage.

- Pancreatic Enzymes:

- Amylase and Lipase: Elevated levels can indicate pancreatitis.

- Indicators of Disease Progression

Enzyme levels can provide information about the severity or progression of a disease.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Elevated levels can indicate tissue damage or certain cancers and are often used to monitor disease progression.

- Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT): Elevated levels can indicate liver disease and can be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

- Assessing Metabolic Disorders

Certain enzyme deficiencies or dysfunctions can lead to metabolic disorders, which can be detected through enzyme assays.

- Phenylketonuria (PKU): A deficiency in phenylalanine hydroxylase can be diagnosed through blood tests in newborns.

- Galactosemia: Deficiency of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase can be diagnosed by measuring enzyme activity in newborn screening.

- Monitoring Treatment Efficacy

Enzyme levels can be monitored to assess the effectiveness of treatments for various conditions.

- Liver Disease: Monitoring liver enzymes during treatment can help evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

- Cancer Treatments: Certain enzyme levels may change in response to chemotherapy or radiation, providing insight into treatment effectiveness.

- Diagnostic Enzyme Assays

Enzyme assays are used in laboratory diagnostics to measure the activity of specific enzymes in blood or other body fluids.

- Enzymatic Assays: These tests measure the concentration or activity of enzymes to help diagnose conditions. For instance, measuring glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity can help diagnose G6PD deficiency.

- Specificity and Sensitivity

The specificity and sensitivity of enzyme assays can provide valuable diagnostic information:

- Specificity: The ability of an enzyme assay to correctly identify the presence of a particular condition without false positives.

- Sensitivity: The ability to detect even low levels of disease markers, crucial for early diagnosis.