Clostridia are significant pathogens responsible for various serious infections, including botulism, tetanus, gas gangrene, and antibiotic-associated colitis. Understanding their characteristics, pathogenic mechanisms, and effective laboratory diagnosis is crucial for managing these infections. Ongoing public health efforts, vaccination programs, and food safety measures are essential for preventing and controlling diseases caused by Clostridia.

General Character

- Genus: Clostridium

- Key Species:

- Clostridium botulinum (causes botulism)

- Clostridium tetani (causes tetanus)

- Clostridium perfringens (causes gas gangrene and food poisoning)

- Clostridium difficile (causes antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and colitis)

- Family: Clostridiaceae

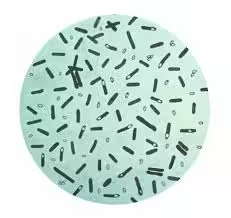

- Gram Staining: Clostridia are Gram-positive, appearing purple due to their thick peptidoglycan layer.

- Shape and Arrangement:

- Shape: Rod-shaped (bacilli) and often larger than other bacteria.

- Arrangement: Usually found as single cells or pairs, some species may form long chains.

- Oxygen Requirements: Clostridia are obligate anaerobes, meaning they cannot survive in oxygen.

Morphology

- Cell Wall Structure:

- Composed of a thick peptidoglycan layer and teichoic acids.

- Endospores: Clostridia can form endospores that are highly resistant to environmental stress (heat, desiccation, chemicals), allowing them to survive in harsh conditions.

Cultural Characteristics

- Growth Media:

- Egg Yolk Agar: Used to identify Clostridium species based on lecithinase production.

- Cooked Meat Medium: A rich anaerobic medium that supports the growth of Clostridia.

- Colony Appearance:

- Colonies of Clostridium species are often irregular, with a flat or raised appearance and a creamy texture.

- Temperature and pH Range:

- The optimal growth temperature is around 30-37°C, with a pH range of 6.5 to 7.5 being favourable.

Biochemical Reactions

- Catalase Test: Clostridia are typically catalase-negative.

- Oxidase Test: Clostridia are oxidase-negative.

- Lactose Fermentation: Variable; some species ferment lactose.

- Urease Test: Variable; many Clostridia do not produce urease.

Pathogenicity

- Virulence Factors:

- Exotoxins: Many Clostridia produce potent exotoxins that contribute to their pathogenicity.

- Enzymes: Some species produce enzymes that degrade host tissues and facilitate spread.

- Clinical Infections:

- Clostridium botulinum: Causes botulism, characterized by paralysis due to the neurotoxin. Symptoms include weakness, double vision, and difficulty swallowing or breathing.

- Clostridium tetani: Causes tetanus, marked by muscle stiffness and spasms due to the tetanospasmin toxin. Initial symptoms often include lockjaw.

- Clostridium perfringens: Causes gas gangrene (a severe tissue infection) and food poisoning (enterotoxin-mediated). Gas gangrene is characterized by severe pain, swelling, and gas production in tissues.

- Clostridium difficile: Associated with antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and colitis, particularly following antibiotic therapy that disrupts normal gut flora. Symptoms range from mild diarrhoea to severe colitis.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Specimen Collection:

- Clinical specimens may include faeces, wound samples, or tissue biopsies.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Gram staining reveals large Gram-positive bacilli, often with a characteristic “boxcar” appearance (especially in C. perfringens).

- Culture Techniques:

- Inoculation on anaerobic media (e.g., egg yolk agar, cooked meat medium) and incubation in anaerobic conditions.

- Biochemical Testing:

- Various tests to identify specific metabolic characteristics and toxin production.

- Molecular Methods:

- PCR and toxin assays can be used for rapid and accurate identification, especially for C. difficile.

Antibiotic Resistance

- Emergence of Resistance:

- Some Clostridium species, particularly C. difficile, have resisted certain antibiotics.

- Treatment Options:

- C. difficile: Treatment typically includes oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Metronidazole may be used in mild cases.

- C. tetani: Tetanus prophylaxis (vaccine and immunoglobulin) is crucial; wounds may be treated with antibiotics (e.g., metronidazole).

- C. botulinum: Antitoxin administration is critical, along with supportive care.

Prevention

- Vaccination: Tetanus is crucial for preventing tetanus; booster shots are recommended every ten years.

- Food Safety: Proper food handling, preservation, and cooking techniques can prevent botulism.

- Hygiene Practices: Good hygiene and prompt treatment of wounds can reduce the risk of Clostridium infections, particularly C. perfringens.