Introduction

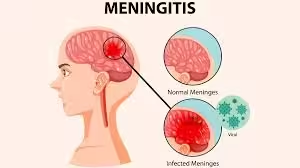

- Meningitis, characterized by the inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord (the meninges), poses significant health risks, particularly when caused by bacterial pathogens.

- The diagnosis of meningitis is critical due to the potential for rapid progression and severe complications, including neurological damage and death.

- This detailed overview examines the laboratory methods used in diagnosing meningitis, including sample collection techniques, laboratory tests, interpretation of results, and the specific approaches for diagnosing various types of meningitis.

Types of Meningitis and Common Pathogens

- Bacterial Meningitis

- Common Pathogens:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: The leading cause of bacterial meningitis in adults and children.

- Neisseria meningitidis: Associated with outbreaks, particularly in crowded settings (e.g., dormitories).

- Haemophilus influenzae type b: Less common due to widespread vaccination.

- Listeria monocytogenes: A significant risk for neonates, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

- Group B Streptococcus: Common in neonates.

- Viral Meningitis

- Common Pathogens:

- Enteroviruses: The most frequent cause of viral meningitis, particularly in children.

- Herpes simplex virus (especially HSV-2) Can cause severe neurological complications.

- Varicella-zoster virus: Also associated with meningitis in some cases.

- Cytomegalovirus: Particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

- Fungal Meningitis

- Common Pathogens:

- Cryptococcus neoformans: Especially prevalent in immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS.

- Histoplasma capsulatum: Can cause meningitis, particularly in endemic regions.

- Parasitic Meningitis

- Common Pathogens:

- Naegleria fowleri: A rare but fatal cause of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, typically contracted from contaminated water.

- Toxoplasma gondii: Can cause meningitis in immunocompromised patients.

Sample Collection

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

CSF analysis is the cornerstone of meningitis diagnosis. It is obtained through a lumbar puncture.

- Procedure:

- Positioning: The patient is typically seated with legs hanging off the table or on their side with knees drawn to the chest.

- Site Selection: The puncture site is usually the L3-L4 or L4-L5 interspace to avoid injury to the spinal cord.

- Sterile Technique: Aseptic technique is essential to minimize the risk of contamination.

- Collection: CSF is collected in sterile tubes, with the first tube reserved for microbiological analysis.

- Volume: Collecting 10–20 mL is generally sufficient for various tests.

- Blood Cultures

- Blood cultures are often obtained simultaneously during lumbar puncture. They are vital for detecting bacteremia, which frequently accompanies bacterial meningitis. At least two blood cultures should be collected from different venipuncture sites to maximize the likelihood of detecting pathogens.

- Other Specimens

- Depending on clinical suspicion, other specimens may be collected, such as:

- Urine: For viral PCR testing in suspected cases of viral meningitis.

- Throat Swabs: For rapid antigen testing of viral pathogens.

- Vesicular Fluid: In cases where herpes simplex virus infection is suspected.

Laboratory Techniques for Diagnosis

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

A. Physical Examination

- Appearance: Normal CSF is clear. Turbidity or cloudiness is indicative of infection.

- Color: Xanthochromia (a yellowish color) may suggest prior hemorrhage or increased protein levels.

B. Chemical Analysis

- Protein Levels: Typically elevated in bacterial and fungal infections; normal or slightly elevated in viral meningitis.

- Glucose Levels: Often decreased in bacterial meningitis (often <40% of serum glucose) while remaining normal in viral meningitis.

- Lactate Levels: Elevated in bacterial meningitis due to anaerobic metabolism.

C. Cell Count and Differential

- Total Cell Count: Elevated WBC counts are indicative of infection.

- Bacterial Meningitis: Usually >1000 cells/mm³, with a predominance of neutrophils.

- Viral Meningitis: Typically <500 cells/mm³, with a predominance of lymphocytes.

Culture Methods

A. Bacterial Culture

- Media Selection: CSF should be inoculated onto various media:

- Blood Agar: A general growth medium that supports most pathogens.

- Chocolate Agar: For fastidious organisms like Haemophilus influenzae.

- Thayer-Martin Agar: A selective medium for Neisseria meningitidis.

- Incubation: Cultures are incubated at 35-37°C in a CO₂-enriched environment for optimal growth.

B. Fungal Culture

- Fungal pathogens are identified through culture on selective media such as Sabouraud dextrose agar, typically requiring longer incubation.

Molecular Methods

A. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

- Nucleic Acid Amplification: PCR is utilized for rapid and specific detection of pathogens in CSF, offering high sensitivity and specificity.

- Viral Pathogens: PCR is particularly effective for detecting enteroviruses and HSV.

- Bacterial Pathogens: Multiplex PCR assays can simultaneously detect multiple bacterial pathogens.

B. Nucleic Acid Hybridization

- FISH (Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization): Can identify specific bacteria directly in CSF samples, useful in polymicrobial infections or when negative culture results.

Serological Tests

- Viral Antigen Detection: Rapid antigen tests can be employed for certain viral pathogens, such as enteroviruses.

- Antibody Detection: While typically not used for acute diagnosis, serology can be valuable in certain infections, such as Listeria, or when diagnosing viral meningitis.

Imaging Studies

- CT or MRI: Imaging studies may be performed before lumbar puncture, especially if there are signs of increased intracranial pressure or focal neurological deficits. This is critical to rule out mass lesions or significant cerebral edema that could complicate lumbar puncture.

Interpretation of Results

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

- Normal Values:

- Protein: 15–45 mg/dL

- Glucose: 2/3 of serum glucose or 45–75 mg/dL

- WBC: 0–5 cells/mm³ (predominantly lymphocytes)

Bacterial Meningitis

- CSF Findings:

- Appearance: Turbid or cloudy

- WBC Count: Elevated, predominantly neutrophils (usually >1000 cells/mm³)

- Protein Levels: Elevated (often >200 mg/dL)

- Glucose Levels: Low (often <40% of serum glucose)

- Lactate Levels: Elevated

- Gram Stain: May reveal organisms; positive in 60-90% of cases.

- Culture: Positive in 70-90% of bacterial meningitis cases.

Viral Meningitis

- CSF Findings:

- Appearance: Clear to slightly cloudy

- WBC Count: Elevated, predominantly lymphocytes (typically <500 cells/mm³)

- Protein Levels: Mildly elevated (usually <150 mg/dL)

- Glucose Levels: Normal (often >60% of serum glucose)

- Culture: Negative for bacteria; viral PCR may be positive.

Fungal Meningitis

- CSF Findings:

- Appearance: Often cloudy or gelatinous

- WBC Count: Elevated, predominantly lymphocytes

- Protein Levels: Significantly elevated (often >100 mg/dL)

- Glucose Levels: Low (though not as markedly as in bacterial meningitis)

- Culture: Positive for fungi (e.g., Cryptococcus) may be confirmed using India ink preparation or mucicarmine stain.

Parasitic Meningitis

- CSF Findings:

- WBC Count: Elevated, typically with eosinophils in cases of parasitic infections.

- Culture: Specific parasitic testing may be required (e.g., Naegleria).

Interpretation of Culture Results

- Positive Culture: Confirms the presence of a pathogen, which helps guide appropriate antibiotic therapy.

- Negative Culture: This may indicate viral meningitis, fastidious bacteria not captured in standard cultures or contamination.

PCR Results

- Positive PCR: Indicates the presence of specific pathogens, particularly valuable for viral meningitis.

- Negative PCR: Suggests that the specific pathogen tested for is not present but does not rule out other pathogens.

Clinical Considerations

Rapid Diagnosis and Treatment

Meningitis is a medical emergency. Empirical treatment should commence immediately based on clinical signs and risk factors, even before laboratory results are available.

- Empirical Treatment: Typically includes broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone and vancomycin for suspected bacterial meningitis). Corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) may also be administered to reduce inflammatory complications.

Follow-Up Testing

Follow-up lumbar punctures may be necessary to assess treatment efficacy, particularly in complicated cases where the clinical response is poor or when specific pathogens are suspected.