Introduction

- Plague is a serious infectious disease caused by Yersinia pestis, which belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family.

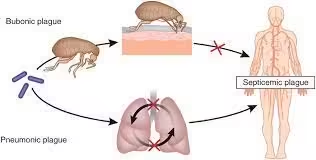

- It primarily affects rodents, and humans can contract it through fleas, direct contact with infected animals, or inhalation of respiratory droplets.

- Historically, plague has been responsible for significant pandemics, most notably the Black Death in the 14th century.

- Today, although rare, outbreaks still occur, particularly in certain regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Clinical Presentation

Plague can manifest in several forms, each with distinct clinical features:

- Bubonic Plague:

- The most common form is characterized by the sudden onset of fever, chills, headache, and the development of painful lymphadenopathy (buboes).

- Buboes typically appear in the groin, armpits, or neck.

- Septicemic Plague:

- Occurs when the bacteria enter the bloodstream, leading to severe symptoms such as high fever, abdominal pain, and necrosis of tissues.

- It can occur as a complication of bubonic plague or as a primary infection without preceding buboes.

- Pneumonic Plague:

- Pneumonia symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis characterize results from inhalation of infectious droplets.

- This form can lead to person-to-person transmission.

Sample Collection

The diagnosis of plague requires the collection of appropriate clinical specimens, which may include:

- Bubo Aspirate: Obtaining fluid from an infected lymph node.

- Blood Samples: Essential for diagnosing septicemic plague; multiple samples may be needed to enhance detection.

- Sputum Samples: For suspected pneumonic plague.

- Tissue Biopsies: From necrotic tissue or organs, especially in severe cases.

Collection Considerations

- Samples should be collected as soon as possible after symptom onset to maximize the likelihood of detecting Y. pestis.

- Precautions should be taken to prevent contamination and protect healthcare workers.

Laboratory Techniques

Microscopy

- Gram Staining

- Procedure: Direct smears of bubo aspirate, blood, or sputum are stained using the Gram stain.

- Observation: Yersinia pestis is small, gram-negative bacilli, often arranged in pairs or short chains. The “safety pin” appearance can be highlighted using Giemsa or Wright’s stain, where the organism shows bipolar staining.

Culture

A. Culture Media

- Blood Agar: Supports the growth of Y. pestis and is used for initial isolation.

- MacConkey Agar: Helps differentiate lactose fermenters from non-fermenters; Y. pestis does not ferment lactose.

B. Incubation

- Cultures should be incubated at 28-30°C for 24-48 hours, as Y. pestis grows optimally at these temperatures.

C. Identification

- Colony Morphology: Y. pestis colonies on blood agar are typically small, smooth, and grayish. Non-hemolytic colonies are observed.

- Biochemical Testing: Y. pestis is urease-negative and oxidase-negative and does not ferment carbohydrates, which helps differentiate it from other enteric bacteria.

Serological Tests

- Passive Hemagglutination: Detects antibodies against Y. pestis but lacks sensitivity and specificity for early diagnosis.

- Complement Fixation Test: Historically used to assess antibodies but is not commonly employed today due to improved methods.

Molecular Methods

A. Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs)

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Highly sensitive and specific for detecting Y. pestis DNA in clinical specimens. Various primers can target specific genes unique to Y. pestis.

B. Real-Time PCR

- Offers quantitative results and faster turnaround times, making it suitable for urgent clinical settings.

C. Multiplex PCR

- It can simultaneously detect multiple pathogens, which is beneficial in differentiating plague from other diseases with similar presentations.

Interpretation of Results

- Microscopy

- Positive Microscopy: The presence of gram-negative bacilli, especially with characteristic bipolar staining, suggests Y. pestis.

- Negative Microscopy: A negative result does not rule out plague, particularly in cases with low bacterial load.

- Culture

- Positive Culture: Isolation of Y. pestis from any clinical specimen confirms the diagnosis.

- Negative Culture: A negative result can occur, especially if antibiotics were administered before sample collection.

- Serological Tests

- Positive Results: May indicate exposure but are not definitive for active infection.

- Negative Results: Cannot exclude plague, particularly in the early stages.

- Molecular Tests

- Positive PCR Result: Confirms the presence of Y. pestis DNA, supporting the diagnosis.

- Negative PCR Result: This may occur if the bacterial load is too low or if sample collection is late during the disease.

Clinical Implications

Treatment

- Prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality:

- First-line antibiotics include streptomycin or gentamicin.

- Alternative options include doxycycline or ciprofloxacin, especially for those with aminoglycoside allergies.

Follow-Up

- Patients should be monitored for response to therapy, potential complications, and recurrence of symptoms.

- Repeat cultures or molecular testing may be warranted to confirm bacterial clearance.

Public Health Considerations

- Plague is a notifiable disease, requiring reporting to health authorities to facilitate outbreak control.

- Public health initiatives should educate communities in endemic areas about prevention and early recognition of symptoms.

Challenges in Diagnosis

- Stigma: The historical context of plague can lead to fear and stigma, potentially delaying patient presentations.

- Clinical Overlap: Symptoms may resemble other infections, such as tularemia or hantavirus, complicating diagnosis.

- Resource Constraints: Limited access to laboratory facilities in endemic regions may hinder timely diagnosis.

Advances in Plague Diagnostics

Emerging Technologies

- Point-of-Care Tests: Development of rapid antigen tests that can be used in field settings to facilitate immediate diagnosis and treatment.

- Whole Genome Sequencing: Used for epidemiological tracking of outbreaks, providing insights into the genetic diversity of Y. pestis and potential resistance mechanisms.

Research Directions

- Ongoing studies focus on understanding the immune response to Y. pestis, which may inform vaccine development and therapeutic strategies.

- Innovations in rapid diagnostics, including lateral flow assays and CRISPR-based detection methods, are under investigation.