Introduction

- Immunoassays are analytical techniques that use the specific binding between an antigen and an antibody to detect and quantify molecules of biological or clinical importance.

- Since the 1960s, when radioimmunoassay (RIA) was first developed, immunoassay technology has advanced tremendously, introducing alternatives that avoid the drawbacks of radioactive methods.

- Among these, the fluorescent immunoassay (FIA) has emerged as one of the most powerful tools, combining immunological specificity with the high sensitivity of fluorescence detection.

- FIA uses fluorophores as labels instead of radioisotopes or enzymes.

- These fluorophores absorb light at a certain wavelength and emit light at a longer wavelength, allowing sensitive measurement of antigen–antibody interactions.

- Due to its unique properties, FIA has become indispensable in clinical diagnostics, biomedical research, pharmacology, food safety, and environmental monitoring.

Definition

A fluorescent immunoassay (FIA) is a laboratory method used to detect and quantify specific biological molecules (antigens or antibodies) by employing fluorophore-labeled immunoreagents.

-

When a fluorophore-labeled antibody binds to its antigen, or vice versa, the complex can be excited with light of a particular wavelength.

-

The emitted fluorescence is detected, and its intensity is proportional to the concentration of the target molecule.

Thus, FIA is defined as:

“An immunoassay that utilizes fluorescent labels to detect and measure antigen–antibody binding reactions with high sensitivity and specificity.”

Principle

The principle of FIA rests on three key foundations: immunological specificity, fluorescence, and quantitative signal measurement.

1 Immunological Specificity

-

Antigens are molecules capable of stimulating an immune response.

-

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that bind to antigens with high specificity at their antigen-binding sites.

-

This lock-and-key mechanism ensures that FIA provides highly selective results.

2 Fluorescence

-

Fluorescence is the ability of a molecule (fluorophore) to absorb photons at an excitation wavelength and emit photons at a longer emission wavelength.

-

Example: Fluorescein absorbs blue light (~490 nm) and emits green light (~520 nm).

-

By tagging antibodies or antigens with fluorophores, binding events can be visualized or quantified.

3 Quantitative Detection

-

The intensity of emitted fluorescence is proportional to the concentration of antigen–antibody complexes.

-

Specialised instruments such as fluorescence microscopes, plate readers, flow cytometers, and spectrofluorometers are used for measurement.

Components

-

Antigen – The target analyte (e.g., protein, hormone, pathogen, toxin).

-

Antibody – Specific immunoglobulin designed to bind antigen.

-

Fluorophore – The fluorescent label attached to antibody or antigen. Common fluorophores include:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)

-

Rhodamine

-

Alexa Fluor dyes

-

Cyanine dyes (Cy3, Cy5)

-

Quantum dots (nanoparticle fluorophores)

-

-

Detection System – Device to measure fluorescence (e.g., fluorometer, microscope, microplate reader).

-

Solid Support (optional) – Nitrocellulose, polystyrene beads, or microplates to immobilize immunoreagents.

Types

FIA can be classified based on assay design and detection strategy:

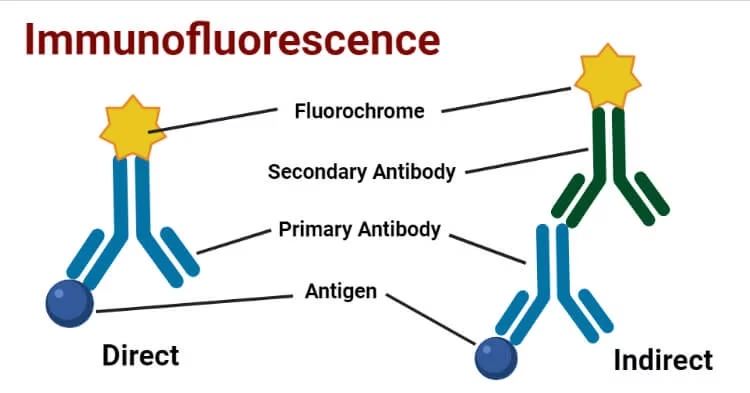

1 Direct Fluorescent Immunoassay (DFA)

-

Antibody specific to the antigen is directly labeled with a fluorophore.

-

When antigen is present, the fluorescent antibody binds and emits signal.

-

Advantages: Fast, fewer steps.

-

Limitations: Lower sensitivity because no signal amplification.

-

Example: DFA test for Rabies virus in brain tissue.

2 Indirect Fluorescent Immunoassay (IFA)

-

Antigen is first bound by an unlabeled primary antibody.

-

A fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody binds the primary antibody.

-

Advantages: Increased sensitivity (multiple secondary antibodies can bind each primary).

-

Example: Detection of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in autoimmune disease diagnosis.

3 Competitive Fluorescent Immunoassay

-

Labeled antigen and unlabeled antigen (sample) compete for antibody binding sites.

-

Higher concentration of unlabeled antigen → lower fluorescence intensity.

-

Useful for small molecules like drugs, hormones, and toxins.

-

Example: Measurement of cortisol levels in serum.

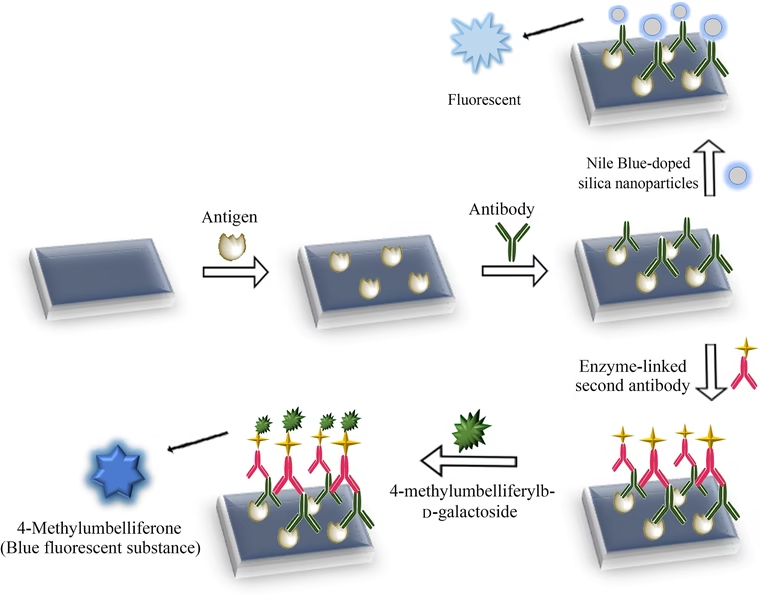

4 Sandwich Fluorescent Immunoassay

-

Antigen is captured by an immobilized antibody.

-

A second, fluorophore-labeled antibody binds a different epitope.

-

Advantages: Very high sensitivity and specificity.

-

Example: Detection of viral proteins, cytokines, and biomarkers.

5 Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay (FPIA)

-

Based on differences in rotational motion of molecules.

-

Free fluorescent antigen rotates rapidly → depolarized emission.

-

Antibody-bound antigen rotates slowly → polarized emission.

-

Application: Therapeutic drug monitoring (e.g., theophylline, cyclosporine).

6 Time-Resolved Fluorescent Immunoassay (TR-FIA)

-

Uses special fluorophores (lanthanides like Europium, Terbium) with long-lived fluorescence.

-

Allows measurement after background autofluorescence has decayed.

-

Advantages: Very high sensitivity, reduced noise.

-

Applications: Detection of very low-abundance biomarkers in clinical samples.

7 Multiplex Fluorescent Immunoassay

-

Uses beads, arrays, or microchips coated with different antibodies, each tagged with distinct fluorophores.

-

Detects multiple analytes simultaneously in a single sample.

-

Example: Luminex xMAP technology – simultaneous detection of 50+ cytokines.

8 Flow Cytometry-Based FIA

-

Fluorescently labeled antibodies bind to cell-surface or intracellular markers.

-

Laser excitation detects fluorescence from individual cells.

-

Application: Immunophenotyping of blood cells, cancer diagnostics, HIV monitoring (CD4 counts).

Applications

FIA has wide-ranging applications across many fields:

1 Clinical Diagnostics

-

Infectious Diseases:

-

DFA for Rabies virus, Chlamydia trachomatis, Respiratory syncytial virus.

-

-

Endocrinology:

-

Measurement of insulin, thyroid hormones, cortisol.

-

-

Oncology:

-

Tumor markers (PSA, CA-125, CEA).

-

-

Autoimmune Disorders:

-

Indirect immunofluorescence for ANA in lupus and other autoimmune diseases.

-

-

Hematology:

-

Blood group antigen typing.

-

2 Biomedical Research

-

Localization of proteins in cells using immunofluorescence microscopy.

-

Tracking cellular signaling pathways.

-

Analysis of protein–protein interactions.

-

High-throughput screening of drug candidates.

3 Pharmaceutical Industry

-

Therapeutic drug monitoring (FPIA assays for antibiotics, immunosuppressants).

-

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies.

-

Biomarker discovery and validation in clinical trials.

4 Food and Agriculture

-

Detection of foodborne pathogens (Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7).

-

Identification of allergens (gluten, peanut proteins).

-

Monitoring of pesticide residues.

5 Environmental Monitoring

-

Detection of toxins in water (cyanobacterial microcystins).

-

Monitoring microbial contamination in soil and water.

-

Identification of endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

6 Point-of-Care Testing

-

Portable FIA devices for bedside testing.

-

Examples:

-

COVID-19 antigen fluorescent assays.

-

Troponin tests for myocardial infarction.

-

Rapid flu and dengue antigen detection kits.

-

Advantages

-

High Sensitivity – Detects femtomolar–picomolar concentrations.

-

High Specificity – Due to antigen–antibody recognition.

-

Multiplexing Capability – Multiple analytes can be measured simultaneously.

-

Wide Dynamic Range – Works over broad concentration ranges.

-

Non-radioactive – Safer than radioimmunoassays.

-

Versatility – Can be adapted to microscopy, flow cytometry, microarrays, or plate assays.

-

Quantitative and Qualitative – Provides both presence/absence and precise concentration.

Limitations

-

Autofluorescence – Some biological samples (blood, tissues) emit natural fluorescence that interferes with signal.

-

Photobleaching – Fluorophores lose fluorescence when exposed to light for prolonged periods.

-

Quenching – Fluorescence can be reduced by chemical interactions or environmental conditions.

-

Cost – High-quality fluorophores and instruments are expensive.

-

Technical Expertise – Requires trained personnel for accurate execution.

-

Cross-Reactivity – Non-specific binding can give false positives.

-

Hook Effect – Extremely high antigen concentration may give falsely low results.

-

Stability Issues – Some fluorophores degrade under temperature or pH changes.

Recent Advances in FIA

-

Quantum Dots (QDs): Nanoparticles with exceptional brightness and photostability.

-

Near-Infrared (NIR) Fluorophores: Reduce background noise and allow deeper tissue penetration.

-

Microfluidic FIA Systems: Lab-on-a-chip devices for rapid, portable analysis.

-

Smartphone-Based FIA: Mobile phone cameras used for fluorescence detection in low-resource settings.

-

AI and Image Analysis: Automated interpretation of immunofluorescence microscopy.

-

Dual-Label and Ratiometric FIAs: Improve accuracy by reducing background fluctuations.