Introduction

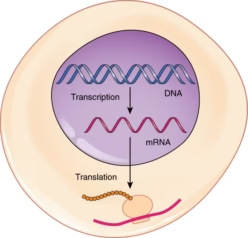

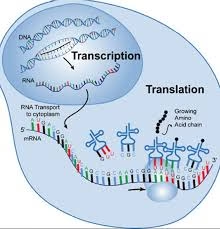

The flow of genetic information in all living organisms follows the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that DNA → RNA → Protein.

-

Transcription is the process of copying genetic information from DNA into RNA.

-

Translation is the process of converting the RNA sequence into a specific protein.

-

These processes ensure that genetic information stored in DNA is expressed as functional proteins, which carry out structural and metabolic roles in the cell.

-

Regulation of transcription and translation is essential for proper growth, development, and adaptation of organisms.

Factors Involved in Transcription and Translation

In Transcription

-

DNA Template: Provides the information for RNA synthesis.

-

RNA Polymerase: Enzyme that synthesizes RNA from DNA template.

-

Promoter Region: DNA sequence where RNA polymerase binds to initiate transcription.

-

Transcription Factors (in eukaryotes): Proteins that help RNA polymerase recognize promoter and regulate gene expression.

-

Ribonucleotides (ATP, GTP, UTP, CTP): Building blocks of RNA.

-

Regulatory Sequences: Enhancers, silencers, and operators that control transcription.

In Translation

-

mRNA: Carries the genetic code from DNA to ribosome.

-

Ribosome: Site of protein synthesis, made of rRNA and proteins.

-

tRNA: Brings amino acids to ribosome according to codon sequence.

-

Amino Acids: Building blocks of proteins.

-

Enzymes (Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase): Attach correct amino acid to its tRNA.

-

Initiation, Elongation, and Release Factors: Proteins that control different stages of translation.

-

GTP/ATP: Energy sources for translation process.

RNA Processing

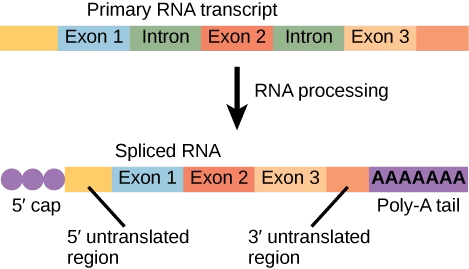

- In eukaryotic cells, the RNA formed directly after transcription is called the primary transcript (pre-mRNA).

- It is not functional and undergoes several modifications to become mature mRNA that can be translated into a protein.

1. Capping (5’ Cap Formation)

-

A 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap is added to the 5’ end of the pre-mRNA.

-

Functions:

-

Protects mRNA from degradation by exonucleases.

-

Helps in ribosome recognition and initiation of translation.

-

2. Polyadenylation (Poly-A Tail Addition)

-

At the 3’ end, a chain of adenine nucleotides (Poly-A tail) is added by poly(A) polymerase.

-

Functions:

-

Increases stability of mRNA.

-

Facilitates transport of mRNA from nucleus to cytoplasm.

-

Helps in efficient translation.

-

3. Splicing

-

Eukaryotic genes contain introns (non-coding regions) and exons (coding regions).

-

Splicing removes introns and joins exons to form a continuous coding sequence.

-

Carried out by a complex called spliceosome (made of snRNA + proteins).

-

Alternative splicing: A single gene can give rise to different proteins by joining exons in different combinations.

4. RNA Editing (in some cases)

-

Nucleotides of RNA may be inserted, deleted, or chemically modified.

-

Changes the coding information.

-

Example: ApoB100 → ApoB48 editing in humans.

Types of RNA

-

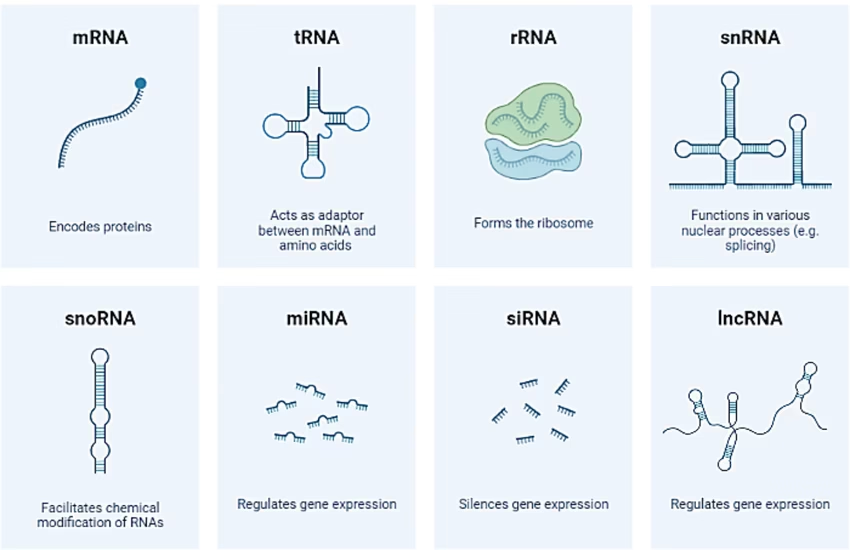

mRNA (Messenger RNA): Carries genetic code from DNA to ribosomes.

-

tRNA (Transfer RNA): Brings specific amino acids during translation.

-

rRNA (Ribosomal RNA): Structural and catalytic component of ribosomes.

-

snRNA (Small nuclear RNA): Involved in splicing of pre-mRNA.

-

miRNA (Micro RNA) & siRNA (Small interfering RNA): Regulate gene expression by silencing or degrading mRNA.

-

lncRNA (Long non-coding RNA): Regulatory functions in gene expression.

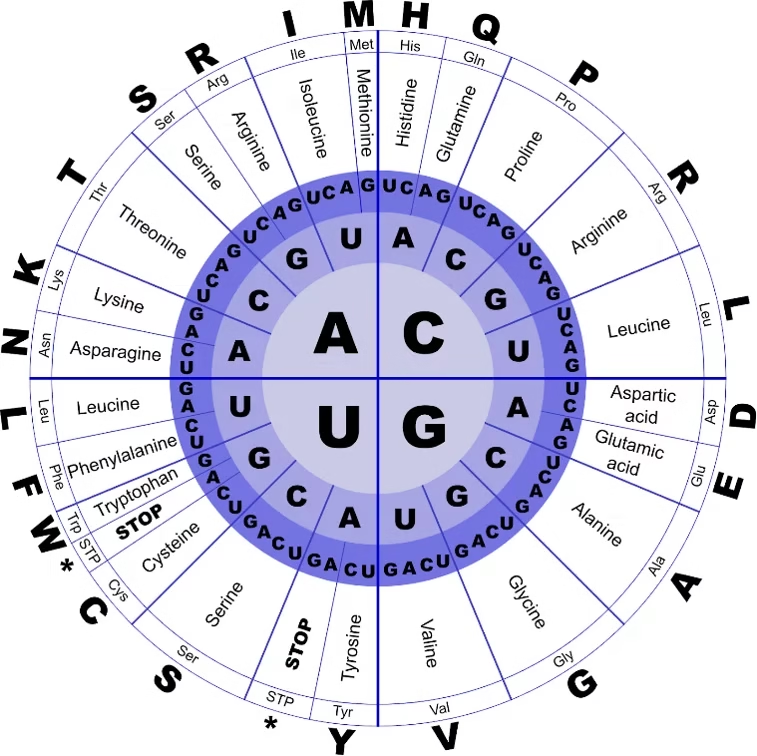

Genetic Code

- The genetic code is the set of rules by which the sequence of nucleotides in mRNA is translated into the sequence of amino acids in a protein.

- It is universal for almost all organisms and ensures that the genetic information in DNA is correctly expressed as proteins.

Features of the Genetic Code

-

Triplet Code

-

Each amino acid is encoded by a sequence of three nucleotides (codon).

-

Example: AUG codes for Methionine.

-

-

Universal

-

The same codon codes for the same amino acid in almost all living organisms (bacteria to humans).

-

-

Degenerate (Redundant)

-

Most amino acids are coded by more than one codon.

-

Example: Leucine is coded by six codons (UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, CUG).

-

-

Unambiguous

-

Each codon specifies only one amino acid.

-

-

Start Codon

-

AUG is the start codon and also codes for Methionine (initiates translation).

-

-

Stop Codons

-

UAA, UAG, UGA → Do not code for any amino acid.

-

They signal termination of protein synthesis.

-

-

Non-overlapping and Commaless

-

Codons are read one after another, without overlapping or punctuation.

-

Types of Codons

-

Sense codons: 61 codons that specify amino acids.

-

Nonsense codons: 3 stop codons (UAA, UAG, UGA).

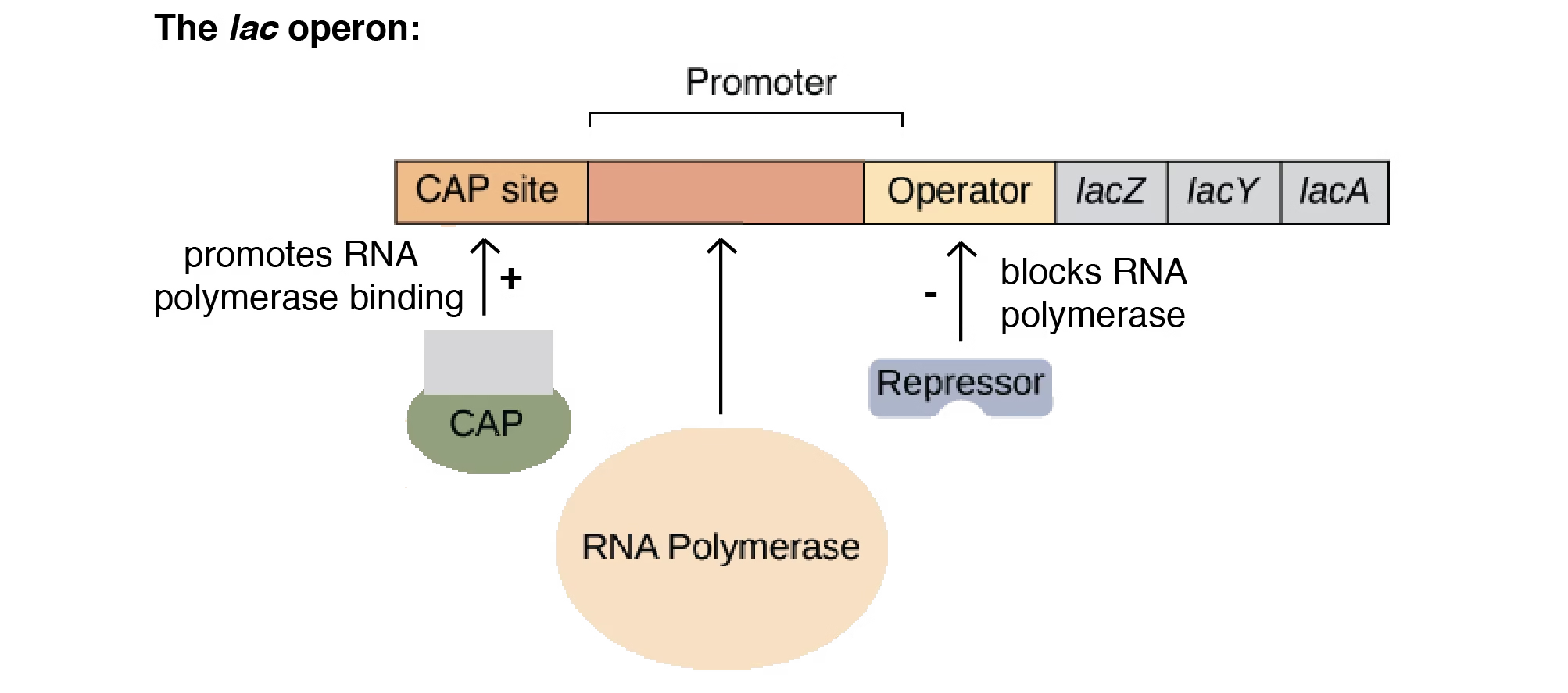

Lac Operon

- The lac operon is a gene regulatory system in Escherichia coli (E. coli) that controls the metabolism of lactose.

- It is a classic example of an inducible operon, meaning it is usually OFF but can be switched ON in the presence of lactose.

Components of Lac Operon

-

Structural Genes

-

lacZ → codes for β-galactosidase (breaks lactose into glucose + galactose).

-

lacY → codes for permease (transports lactose into the cell).

-

lacA → codes for transacetylase (detoxifies by-products).

-

-

Regulatory Elements

-

Promoter (P): Site where RNA polymerase binds to start transcription.

-

Operator (O): Site where the repressor binds to block transcription.

-

Regulator Gene (lacI): Produces repressor protein that controls the operon.

-

Working of Lac Operon

-

Without Lactose (Operon OFF):

-

Repressor protein binds to operator.

-

RNA polymerase cannot move forward.

-

No transcription of structural genes.

-

-

With Lactose (Operon ON):

-

Lactose is converted into allolactose (inducer).

-

Allolactose binds to repressor → inactivates it.

-

RNA polymerase binds promoter and transcribes structural genes.

-

Enzymes are produced for lactose metabolism.

-

Regulation by Glucose (Catabolite Repression)

-

When glucose is present, the lac operon remains mostly OFF even if lactose is available.

-

cAMP-CAP complex is required for efficient transcription.

-

Low glucose → High cAMP → cAMP binds CAP → enhances transcription.

-

High glucose → Low cAMP → CAP does not bind → transcription reduced.

-

Tryptophan (Trp) Operon

- The tryptophan operon is a gene regulatory system in Escherichia coli (E. coli) that controls the biosynthesis of the amino acid tryptophan.

- It is a classic example of a repressible operon, meaning it is usually ON but can be turned OFF when tryptophan is abundant.

Components of Trp Operon

-

Structural Genes (trpE, trpD, trpC, trpB, trpA)

-

Encode enzymes required for synthesis of tryptophan.

-

-

Regulatory Elements

-

Promoter (P): Site where RNA polymerase binds.

-

Operator (O): Binding site for the repressor.

-

Regulator Gene (trpR): Produces an inactive repressor protein.

-

Leader Sequence (trpL): Involved in fine regulation by attenuation.

-

Mechanism of Regulation

-

When Tryptophan is Absent (Operon ON):

-

Repressor protein is inactive and cannot bind the operator.

-

RNA polymerase binds to promoter and transcribes the structural genes.

-

Enzymes are synthesized → Tryptophan is produced.

-

-

When Tryptophan is Present (Operon OFF):

-

Tryptophan acts as a co-repressor.

-

It binds to the inactive repressor protein, activating it.

-

The active repressor binds to the operator and blocks RNA polymerase.

-

Transcription of structural genes stops → No unnecessary tryptophan synthesis.

-

Attenuation (Extra Control Mechanism)

-

In addition to repression, the trp operon also uses attenuation for regulation.

-

The leader region (trpL) contains short sequences that can form hairpin loops in mRNA.

-

When tryptophan levels are high → ribosome moves quickly → forms a terminator loop → transcription stops early.

-

When tryptophan levels are low → ribosome stalls → forms anti-terminator loop → transcription continues.

Regulation in Eukaryotes

Gene regulation in eukaryotes is more complex than in prokaryotes because:

-

DNA is packaged into chromatin.

-

Genes are separated by introns and exons.

-

Multiple levels of control exist (before transcription to after protein synthesis).

This regulation ensures cell differentiation, development, and adaptation.

Levels of Gene Regulation in Eukaryotes

1. Epigenetic Regulation (Chromatin Level)

-

Histone Modification: Acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation of histones control accessibility of DNA.

-

Histone acetylation: Opens chromatin → increases transcription.

-

Histone deacetylation: Condenses chromatin → decreases transcription.

-

-

DNA Methylation: Addition of methyl groups to cytosine → silences genes.

-

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes: Rearrange nucleosomes to allow or block transcription.

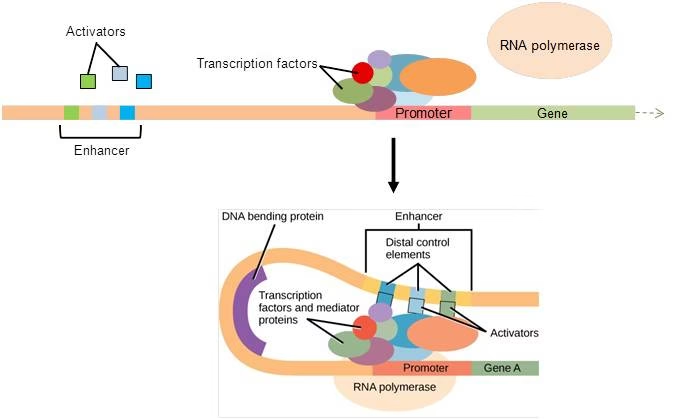

2. Transcriptional Regulation

-

Promoters: DNA sequences where RNA polymerase binds.

-

Enhancers & Silencers: Regulatory sequences that increase or decrease transcription.

-

Transcription Factors: Proteins that bind DNA to regulate gene expression (activators & repressors).

-

Mediator Complex: Connects transcription factors with RNA polymerase.

3. Post-Transcriptional Regulation

-

Alternative Splicing: A single pre-mRNA can give rise to different mRNAs and proteins.

-

RNA Editing: Nucleotide modifications can change coding information.

-

RNA Transport: Export of mRNA from nucleus to cytoplasm can be controlled.

-

mRNA Stability: Poly-A tail length and binding proteins regulate how long mRNA remains functional.

4. Translational Regulation

-

Control of Initiation: Proteins and initiation factors regulate the binding of ribosomes to mRNA.

-

miRNA & siRNA: Small RNAs bind to mRNA and prevent translation or degrade it (RNA interference).

5. Post-Translational Regulation

-

Protein Folding & Modifications: Proteins may undergo phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation.

-

Protein Degradation: Ubiquitin-proteasome system marks proteins for destruction.

-

Compartmentalization: Proteins activated only when transported to correct organelle.

Gene Dosage and Gene Amplification

1. Gene Dosage

-

Definition: Gene dosage refers to the number of copies of a particular gene present in a cell or organism.

-

Normally, each gene is present in two copies (diploid) in humans.

-

If the number of gene copies changes, the expression level of that gene also changes.

Effects of Gene Dosage:

-

Increased dosage: More copies → excess production of gene product (protein).

-

Decreased dosage: Fewer copies → reduced gene product.

Examples:

-

Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Extra copy of chromosome 21 → higher gene dosage.

-

Turner Syndrome (XO): Only one X chromosome → lower gene dosage of X-linked genes.

2. Gene Amplification

-

Definition: Gene amplification is the increase in the number of copies of a specific gene within a cell.

-

It is a controlled process and often occurs when cells need large amounts of a specific product.

Examples:

-

rRNA Genes: Amplified in rapidly dividing cells to meet high protein synthesis demand.

-

Oncogenes in Cancer: Amplification of genes like HER2/neu in breast cancer leads to uncontrolled cell growth.

-

In Insects: Amplification of detoxifying enzyme genes provides resistance against pesticides.

Difference Between Gene Dosage and Gene Amplification

| Feature | Gene Dosage | Gene Amplification |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Change in number of whole gene copies due to chromosomal abnormalities. | Increase in copies of a particular gene within the genome. |

| Cause | Chromosome gain/loss (aneuploidy). | Specific gene replication. |

| Effect | Global effect on all genes of that chromosome. | Local effect on a single/few genes. |

| Example | Down syndrome (extra chromosome 21). | HER2 gene amplification in cancer. |

Generation of Antibody Diversity

- The immune system can produce millions of different antibodies to recognize a vast array of antigens, even though the genome contains a limited number of antibody genes.

- This diversity is generated by several mechanisms in B-cells.

1. V(D)J Recombination

-

Definition: Random rearrangement of gene segments in B-cells.

-

Components:

-

V (Variable) segments

-

D (Diversity) segments – only in heavy chains

-

J (Joining) segments

-

-

During B-cell development, different V, D, and J segments are combined to create a unique variable region of the antibody.

-

Result: Generates a large variety of antigen-binding sites.

2. Junctional Diversity

-

During V(D)J recombination, random addition or deletion of nucleotides occurs at the joining sites.

-

This further increases variability in the antibody’s antigen-binding site.

3. Somatic Hypermutation

-

Occurs after antigen stimulation in mature B-cells.

-

Introduces point mutations in the variable region of antibody genes.

-

B-cells producing higher-affinity antibodies are selected → affinity maturation.

4. Class Switch Recombination (Isotype Switching)

-

Changes the constant region of the antibody heavy chain without altering the antigen specificity.

-

Allows the antibody to switch from IgM → IgG, IgA, or IgE depending on the immune response.

5. Combinatorial Association

-

Each antibody has two heavy chains and two light chains.

-

Different combinations of heavy and light chains further increase diversity.