Dracunculus is a genus of parasitic nematodes that cause dracunculiasis (also known as Guinea worm disease). The disease is transmitted through ingesting contaminated water containing the larvae of Dracunculus medinensis, the most well-known species responsible for the disease.

Habitat

- Dracunculus species, particularly Dracunculus medinensis, inhabit the host’s subcutaneous tissue, where the female worm resides, often in the lower limbs or other body parts.

- The larvae and microfilariae (larval stage) are released into contaminated water sources when the infected individual’s blisters rupture and release larvae, which freshwater copepods can consume.

- Humans and other mammals (like dogs, pigs, and other animals) are definitive hosts, and freshwater copepods act as the intermediate hosts for the larval stages.

Epidemiology

- Dracunculiasis is primarily found in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, particularly in regions with limited access to clean drinking water and sanitation.

- The disease has historically been a major health problem in South Sudan, Chad, Ethiopia, and other countries in West Africa.

- The transmission cycle depends on the presence of copepods that are infected with Dracunculus larvae. Humans become infected when they drink contaminated water containing these infected copepods.

- Dracunculiasis is a preventable disease, and efforts to eradicate it have been ongoing, with the World Health Organization (WHO) coordinating large-scale water treatment and health education programs.

Morphology

- Adult Females: The female Dracunculus worm is the largest, reaching up to 80 cm to 120 cm in length, although some can grow even longer. The female worm is white or cream-colored and appears coiled in the subcutaneous tissue.

- The female is long and slender with a sharp anterior end, which allows it to migrate through tissues. Upon maturity, the female worm moves toward the skin’s surface, usually in the lower limbs, creating a blister.

- Adult Males: The male is much smaller, about 2-4 cm long. It does not migrate to the surface but remains in the deeper tissue, fertilizing the female.

- Larvae (Microfilariae): The larvae, released from the ruptured blister, are microscopic and can be observed in contaminated water sources. They are motile and are ingested by freshwater copepods, which serve as intermediate hosts.

Life Cycle

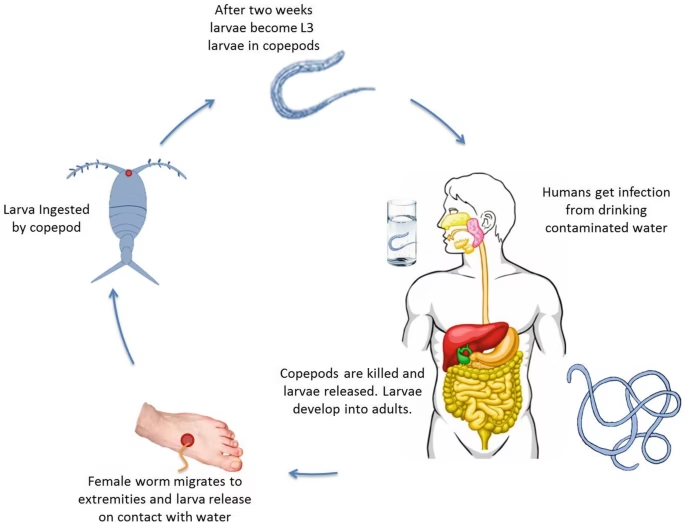

The life cycle of Dracunculus involves a definitive host (human) and an intermediate host (copepod):

- Ingestion of Copepods:

- Humans ingest water contaminated with infected copepods (small crustaceans). The copepods contain Dracunculus larvae in the form of larvae (L3).

- Larvae in the Stomach:

- Once in the stomach, the copepods are digested, and the larvae are released into the intestinal tract.

- Migration to Subcutaneous Tissue:

- The larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate through the lymphatic system into the subcutaneous tissues (especially the lower limbs).

- Mating and Development:

- The female worm grows larger (up to 1 meter long) and migrates to the skin’s surface, while the male dies after mating with the female.

- The female worm gradually emerges through the skin, forming a painful blister (usually on the feet, legs, or other areas), where it waits to release larvae.

- Release of Larvae:

- When the blister ruptures, thousands of larvae are released into the surrounding water, which can be consumed by copepods, restarting the cycle.

Pathogenesis

- Dracunculus worms cause dracunculiasis when the female worms migrate through the subcutaneous tissue, typically in the lower limbs, and create blisters. The inflammation caused by the presence of the worm leads to pain, redness, and swelling in the affected area.

- The worms can remain embedded in the tissue for several months, gradually causing severe discomfort.

- Toxic reactions may occur as the worm comes closer to the skin’s surface, and secondary bacterial infections can develop at the site of the blister.

- Secondary complications include skin ulcers, cellulitis, and occasionally gangrene if the infection is not treated. In some cases, worms can cause severe pain and even disability.

- Delayed Symptoms: After the initial skin lesion heals, systemic symptoms like fever, nausea, and vomiting may occur due to the release of toxins and bacterial contamination.

- Death is rare but can occur if there is widespread infection leading to sepsis or complications from secondary infections.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dracunculiasis can be confirmed by clinical signs and laboratory tests, including:

- Clinical Diagnosis:

- A diagnosis can be made based on the characteristic presentation of blisters on the skin, usually in the lower limbs. The presence of the worm may be visible through the blister or skin ulcer.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Larvae (microfilariae) can be detected under the microscope in water samples from contaminated sources, confirming the presence of Dracunculus larvae in the environment.

- Skin biopsy or fluid samples from the ruptured blister may contain larvae, which can be examined under the microscope.

- Detection of Antibodies:

- In some cases, serological tests (e.g., ELISA) may be used to detect Dracunculus-specific antibodies. However, such tests are not widely used for routine diagnosis due to the focus on eradicating the disease.

- Imaging:

- Ultrasound or X-rays may sometimes be used to locate and confirm the presence of worms beneath the skin, although this is less common.

- Confirmation via Worm Extraction:

- The most definitive method for diagnosis is the extraction of the adult female worm from the blister site. The female worm can be pulled from the skin slowly and progressively (over several weeks if necessary).

Summary Table: Dracunculus (Guinea Worm Disease)

| Aspect | Dracunculus (Guinea Worm) |

| Habitat | The subcutaneous tissue of humans and other mammals |

| Epidemiology | Found primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, transmitted via contaminated water containing infected copepods |

| Morphology | Female (80-120 cm), Male (2-4 cm); larvae are microscopic |

| Life Cycle | Involves intermediate hosts (copepods) and definitive hosts (humans), with the larvae released in water after being ingested by copepods |

| Pathogenesis | Blisters form on the skin, causing pain, inflammation, and risk of secondary infections; can lead to long-term disability |

| Laboratory Diagnosis | Microscopy of water or biopsies, serological tests, clinical signs, and worm extraction |

Prevention and Control

- The disease is primarily preventable through access to safe drinking water.

- Safe water sources: Filter water to remove copepods or use chlorination methods.

- Health education: Teaching populations to avoid drinking untreated water and to use filters.

- Eradication efforts by the World Health Organization (WHO) have significantly reduced the number of reported cases globally. The ultimate goal is complete eradication, as the worm only infects humans.