Introduction

- The microscopic examination of urine analysis is a crucial part of a complete urinalysis.

- This test identifies invisible elements to the naked eye, such as cells, crystals, casts, and microorganisms.

- It is performed by centrifuging a urine sample to concentrate the sediment and then examined under a microscope.

- This examination provides important diagnostic information for conditions affecting the kidneys, urinary tract, and systemic diseases.

Principle

The microscopic elements in urine (in suspension) are collected as deposits by centrifugation. A small drop of the sediments is examined by making a coverslip preparation under the microscope.

Requirements

- Centrifuge tubes or test tubes

- Glass slides

- Coverslip

- Pasteur pipettes

Instruments

- Centrifuge

- Microscope

Specimen

Freshly voided, midstream Morning urine

Procedure:

- Collection of Urine Samples:

- Use a clean-catch midstream urine sample to avoid contamination.

- For optimal results, urine should be fresh, preferably analyzed within 1-2 hours of collection.

- In cases where immediate analysis is impossible, the sample should be stored in a refrigerator (2-8°C) to prevent bacterial growth or decomposition.

Cloudy urine in the specimen container.

- Mixing the Sample:

- Before testing, gently mix the urine sample to distribute the components evenly. Avoid vigorous shaking to prevent frothing or air bubbles.

- Centrifugation:

- Pour 10-15 mL of well-mixed urine into a conical centrifuge tube.

- Place the tube in a centrifuge and spin at 1,500 to 2,000 revolutions per minute (RPM) for 5 minutes. This process will cause solid particles (cells, casts, crystals) to settle at the bottom of the tube, forming a sediment.

- Decanting the Supernatant:

- After centrifugation, gently pour off the supernatant (the clear liquid above the sediment), leaving approximately 5 mL of urine at the bottom. Be careful not to disturb the sediment.

- Alternatively, use a pipette to remove the supernatant without losing the sediment.

- Preparing the Sediment for Examination:

- Resuspend the sediment by gently tapping or swirling the tube.

- A Pasteur pipette transfers a small sediment drop onto a clean glass microscope slide.

- Place a coverslip over the drop to avoid drying and distortion of the sample.

- Microscopic Examination:

- Examining the sample under low power magnification (10x objective) to identify larger elements such as casts and crystals.

- Next, switch to high power magnification (40x objective) for a detailed evaluation of cells (RBCs, WBCs, epithelial cells), bacteria, yeast, and parasites.

- Use appropriate light intensity and contrast adjustments to enhance visibility.

Observations

-

Cells:

- Red Blood Cells (RBCs):

Pyuria or leukocyturia is the condition of urine containing white blood cells or pus. It can be a sign of a bacterial urinary tract infection - Normally, 0-2 RBCs per high power field (HPF) are considered within the normal range.

- Increased RBCs (Hematuria) may indicate:

- Glomerulonephritis: RBCs may be dysmorphic, indicating damage to the glomerulus.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) or kidney stones: Intact RBCs may indicate trauma or irritation.

- Tumors: In the urinary tract or bladder.

- Coagulopathy: Bleeding disorders or conditions affecting blood clotting.

- Appearance: Normal RBCs are biconcave discs, but in glomerular diseases, they can appear misshapen or fragmented (dysmorphic RBCs).

- White Blood Cells (WBCs):

- Normally, 0-5 WBCs/HPF are considered normal.

- Increased WBCs (Pyuria) suggest infection, inflammation, or other issues:

- Urinary tract infection (UTI): WBCs are present in response to bacterial infections in the bladder, urethra, or kidneys.

- Interstitial nephritis: Inflammation of the kidney interstitium.

- Kidney stones: May cause irritation and inflammation, leading to an increase in WBCs.

- Appearance: WBCs are typically larger than RBCs and may have visible nuclei. They can sometimes clump together in severe infections.

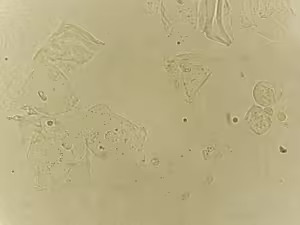

- Epithelial Cells:

Epithelial cells with bacteria in patient urine urinary tract infections, analysed by microscope - Squamous epithelial cells:

- These cells originate from the urethra or external genitalia.

- A large number of squamous epithelial cells may indicate sample contamination from skin or vaginal secretions.

- Transitional epithelial cells:

- These cells line the bladder, ureters, and renal pelvis.

- They can be seen in bladder infections or trauma to the urinary tract.

- Increased numbers may indicate bladder inflammation or irritation.

- Renal tubular epithelial cells:

- These are more clinically significant and indicate injury to the renal tubules.

- They are often seen in acute tubular necrosis (ATN), kidney transplant rejection, or toxicity from drugs or heavy metals.

- Appearance: Larger than WBCs, often round or oval, with a large nucleus.

- Squamous epithelial cells:

- Red Blood Cells (RBCs):

-

Casts:

Casts are cylindrical particles formed from coagulated proteins secreted by kidney tubules. They take the shape of the renal tubules and often indicate kidney disease.

-

- Hyaline Casts:

- Composed primarily of Tamm-Horsfall protein.

- They are generally considered normal, especially after exercise or dehydration.

- Increased numbers can indicate mild kidney stress or non-specific kidney issues.

- Hyaline Casts:

-

Crystals:

Urinary crystals can form when substances in the urine become concentrated and begin to solidify. The presence of crystals can suggest metabolic conditions, dietary influences, or the potential for kidney stone formation.

-

- Calcium Oxalate Crystals:

Microscopic image showing calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal from urine sediment. kidney disease. 400x - Common in normal urine but can indicate kidney stones.

- Appear in two forms:

- Dihydrate form: Envelope-shaped.

- Monohydrate form: Dumbbell-shaped, often seen in ethylene glycol poisoning.

- Uric Acid Crystals:

- Seen in acidic urine (pH < 6).

- It can indicate gout or high purine metabolism.

- Appearance: Rhombus or barrel-shaped, may appear in a variety of shapes.

- Struvite Crystals (Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate):

- Often associated with UTIs caused by urease-producing bacteria.

- It can form struvite stones, common in infected urine.

- Appearance: Coffin-lid shape.

- Cystine Crystals:

- Indicate cystinuria, a rare genetic disorder that leads to the formation of cystine stones.

- Appearance: Hexagonal and colourless.

- Other Crystals:

- Ammonium biurate (thorn-apple shape) indicates old or poorly preserved urine.

- Cholesterol crystals may suggest nephrotic syndrome.

- Calcium Oxalate Crystals:

-

Microorganisms:

- Bacteria:

Microscopic image of abnormal urinalysis. urine exam. - Normally absent. The presence of bacteria indicates a urinary tract infection (UTI).

- Bacteriuria is often confirmed alongside symptoms like pyuria (WBCs in urine).

- It may be classified as Gram-positive or Gram-negative upon culture.

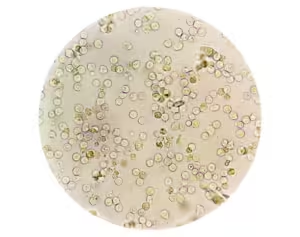

- Yeast:

- Commonly Candida species.

- Yeast in the urine can indicate a yeast infection or contamination, especially in diabetic or immunocompromised patients.

- Appearance: Budding yeast cells or pseudohyphae may be visible.

- Parasites:

- Trichomonas vaginalis: A sexually transmitted parasite that can be seen in wet mount preparations of urine. It has a characteristic pear shape and flagella.

- Rarely, other parasites may be found in urine, depending on endemic regions and patient exposure.

- Bacteria:

-

Other Particles:

- Mucus:

- Small amounts are normal, but larger amounts may suggest inflammation or infection.

- Spermatozoa:

- It may appear in urine after ejaculation, typically without clinical significance.

- Artifacts:

- Contaminants such as talc, fibres, or powder may be seen, especially if the urine sample is collected improperly.

- Mucus:

Reporting the Results:

- Record the number of cells, casts, crystals, and organisms seen per high-power field (HPF) or low-power field (LPF) as appropriate.

- Report findings based on their clinical significance (e.g., “numerous WBCs indicating pyuria,” “moderate calcium oxalate crystals suggesting possible kidney stones”).

Quality Control:

- Ensure that the microscope is properly calibrated and that reagents (if any) are current.

- Ensure proper hygiene, handling, and storage of samples to prevent contamination.

- Cross-check findings with chemical tests (such as dipstick results) for consistency.

Interpretation:

- The microscopic findings must be interpreted with the patient’s clinical presentation, history, and other diagnostic tests.

- Abnormal findings (e.g., hematuria, pyuria, casts, or crystals) may lead to further diagnostic evaluations or treatments.