Sources of Amino Acids

-

Dietary proteins – obtained from food and digested into amino acids.

-

Degradation of body (tissue) proteins – due to normal protein turnover.

-

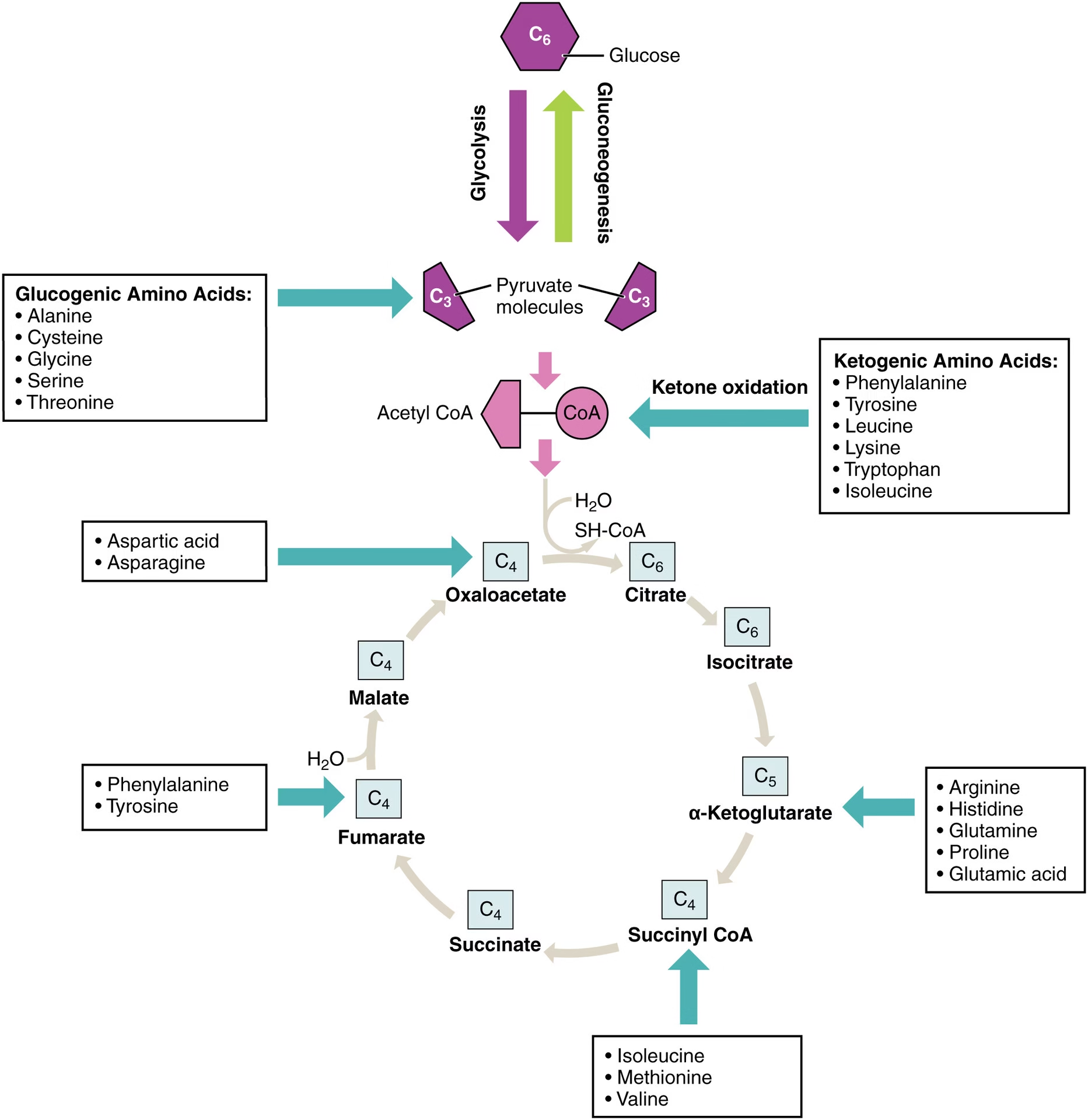

De novo synthesis – synthesis of non-essential amino acids from metabolic intermediates of glycolysis, TCA cycle, or pentose phosphate pathway.

-

Transamination reactions – interconversion among different amino acids.

-

Ammonia assimilation – formation of amino acids from ammonia and α-keto acids (e.g., glutamate synthesis).

Deamination:

Definition:

Deamination is the process by which an amino group (–NH₂) is removed from an amino acid, forming ammonia (NH₃) and a corresponding keto acid.

Types:

-

Oxidative Deamination: Removal of amino group with oxidation.

-

Enzyme: Glutamate dehydrogenase

-

Reaction: Glutamate + NAD⁺ + H₂O → α-Ketoglutarate + NH₃ + NADH

-

Site: Liver mitochondria

-

-

Non-oxidative Deamination: Removal of the amino group without oxidation.

-

Examples: Serine, threonine, and histidine undergo this type.

-

Importance:

-

Releases free ammonia for urea synthesis.

-

Produces keto acids for energy production, gluconeogenesis, or fatty acid synthesis.

-

Maintains nitrogen balance in the body.

Metabolism of Ammonia

1. Formation of Ammonia:

Ammonia is produced in the body from several sources:

-

Oxidative deamination of glutamate (via glutamate dehydrogenase).

-

Deamidation of glutamine and asparagine.

-

Transamination followed by deamination.

-

Bacterial action in the intestine (urease activity on urea).

2. Transport of Ammonia:

Because ammonia is toxic, it is transported in non-toxic forms:

-

As Glutamine:

-

Enzyme: Glutamine synthetase

-

NH₃ + Glutamate → Glutamine (in peripheral tissues)

-

Glutamine travels to the liver or kidney where it is hydrolyzed back to NH₃.

-

-

As Alanine:

-

Formed in muscle via alanine transaminase (ALT).

-

Alanine carries ammonia to the liver for conversion to urea (Glucose–Alanine cycle).

-

3. Detoxification and Excretion:

-

In Liver:

-

Ammonia is converted into urea by the urea cycle (main pathway of detoxification).

-

-

In Kidney:

-

Small amount of ammonia is directly excreted in urine as NH₄⁺ to help maintain acid–base balance.

-

4. Utilization:

-

Small amounts are used in the synthesis of amino acids, purines, pyrimidines, and glutamine.

5. Toxicity:

-

Excess ammonia causes hyperammonemia, leading to CNS symptoms (confusion, tremor, coma).

-

Normally, blood ammonia is kept below 50 µmol/L by efficient liver function.

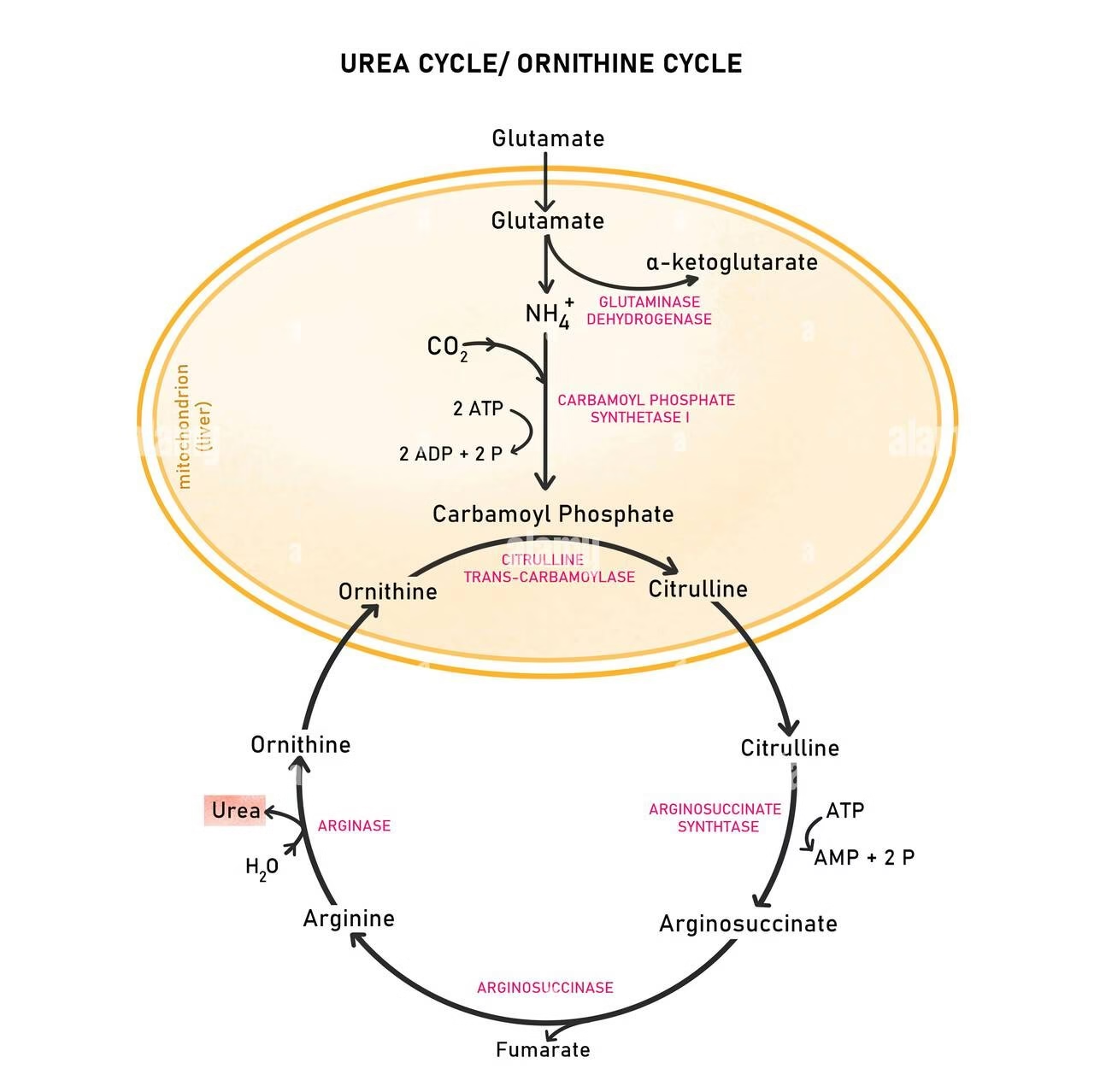

Formation of Urea

Definition:

- The urea cycle (also called the ornithine cycle) is the biochemical pathway in the liver by which toxic ammonia (NH₃), produced from amino acid catabolism, is converted into non-toxic urea, which is then excreted by the kidneys.

- It was discovered by Hans Krebs and Kurt Henseleit in 1932 and represents the first cyclic metabolic pathway identified.

Site of Occurrence:

-

Organ: Liver (hepatocytes)

-

Subcellular Location:

-

Mitochondria: First two reactions

-

Cytosol: Last three reactions

-

Precursors of Urea:

Urea contains two nitrogen atoms and one carbon atom:

| Atom | Source |

|---|---|

| One nitrogen | From ammonia (NH₃) produced by oxidative deamination of glutamate |

| Second nitrogen | From aspartate formed by transamination of oxaloacetate |

| Carbon atom | From CO₂ (as bicarbonate, HCO₃⁻) |

Steps of Urea Formation:

Step 1 – Formation of Carbamoyl Phosphate

-

Enzyme: Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I (CPS I)

-

Location: Mitochondria

-

Reaction:

NH3+CO2+2ATP→Carbamoyl phosphate+2ADP+Pi

-

Cofactor: N-Acetylglutamate (NAG) – an essential allosteric activator.

-

Significance: This is the rate-limiting step of the cycle.

Step 2 – Formation of Citrulline

-

Enzyme: Ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC)

-

Location: Mitochondria

-

Reaction:

Ornithine+Carbamoyl phosphate→Citrulline+Pi

-

Process: Citrulline is then transported to the cytosol via an ornithine–citrulline antiporter.

Step 3 – Formation of Argininosuccinate

-

Enzyme: Argininosuccinate synthetase

-

Location: Cytosol

-

Reaction:

Citrulline+Aspartate+ATP→Argininosuccinate+AMP+PPi

-

Significance:

-

Aspartate contributes the second nitrogen of urea.

-

Uses two high-energy phosphate bonds (ATP → AMP).

-

Step 4 – Cleavage of Argininosuccinate

-

Enzyme: Argininosuccinate lyase (Argininosuccinase)

-

Location: Cytosol

-

Reaction:

Argininosuccinate→Arginine+Fumarate

-

Significance:

-

Fumarate enters the TCA cycle, forming malate and oxaloacetate (link between the two cycles).

-

This connection is known as the Aspartate–Argininosuccinate shunt.

-

Step 5 – Formation of Urea and Regeneration of Ornithine

-

Enzyme: Arginase

-

Location: Cytosol

-

Reaction:

Arginine+H2O→Urea+Ornithine

-

Significance:

-

Urea is released into blood → transported to kidneys → excreted in urine.

-

Ornithine is recycled back into mitochondria to continue the cycle.

-

Overall Reaction:

2NH3+CO2+3ATP+H2O→Urea+2ADP+AMP+4Pi+

-

Energy cost: 3 ATP (4 high-energy bonds) are used for each molecule of urea synthesized.

-

Energy recovery: Oxidation of fumarate via TCA cycle yields ~1 NADH (≈ 3 ATP), partly compensating energy expenditure.

Regulation of Urea Cycle:

-

Allosteric Regulation:

-

CPS I is activated by N-Acetylglutamate (NAG).

-

Arginine stimulates NAG synthesis → increases urea cycle activity.

-

-

Substrate Availability:

-

Increased ammonia or amino acid load enhances urea formation.

-

-

Enzyme Induction:

-

High-protein diet or fasting induces the synthesis of urea cycle enzymes.

-

Physiological Significance:

-

Ammonia detoxification: Converts toxic NH₃ to non-toxic urea.

-

Nitrogen excretion: Main pathway for nitrogen elimination.

-

Interconnection with energy metabolism: Fumarate links to the TCA cycle.

-

Maintenance of acid–base balance: Prevents ammonia accumulation, which raises pH.

Clinical Correlations:

1. Hyperammonemia:

-

Elevated blood ammonia due to defective urea formation.

-

Causes:

-

Liver disease (acquired)

-

Congenital enzyme deficiencies (inherited)

-

2. Enzyme Deficiencies and Disorders:

| Enzyme Deficiency | Disorder | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| CPS I | Hyperammonemia Type I | ↑ NH₃, ↓ citrulline |

| OTC | Hyperammonemia Type II | ↑ NH₃, ↑ orotic acid (X-linked) |

| Argininosuccinate synthetase | Citrullinemia | ↑ Citrulline |

| Argininosuccinate lyase | Argininosuccinic aciduria | ↑ Argininosuccinate |

| Arginase | Hyperargininemia | ↑ Arginine, neurological symptoms |

3. Symptoms:

Vomiting, lethargy, seizures, cerebral edema, coma.

4. Treatment:

-

Dietary: Low-protein diet

-

Drugs: Sodium benzoate, phenylacetate, or phenylbutyrate (bind excess ammonia)

-

Supplement: Arginine or citrulline (depending on deficiency)

-

Severe cases: Liver transplantation

Quantitative Aspect:

-

Daily urea excretion: 25–30 g/day in adults.

-

Constitutes about 80–90% of total urinary nitrogen.

Link with Other Metabolic Pathways:

| Cycle/Pathway | Connection |

|---|---|

| TCA Cycle | Fumarate from urea cycle enters TCA; CO₂ from TCA used in CPS I reaction. |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | Provides ammonia and aspartate. |

| Transamination Reactions | Form aspartate and glutamate, key intermediates. |

Mnemonic for Enzymes (in order):

C – O – A – A – A

-

-

C – Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I

-

O – Ornithine transcarbamoylase

-

A – Argininosuccinate synthetase

-

A – Argininosuccinate lyase

-

A – Arginase

-

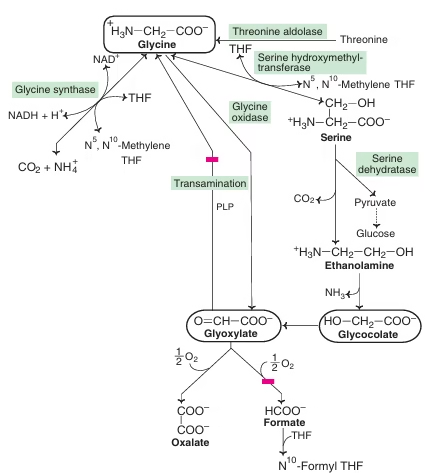

Glycine Metabolism

Introduction

-

Glycine is the simplest amino acid (NH₂-CH₂-COOH).

-

It is non-essential, glucogenic, and plays key roles in protein synthesis, one-carbon metabolism, and biosynthesis of important biomolecules.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | C₂H₅NO₂ |

| Molecular Weight | 75 Da |

| Nature | Non-essential, glucogenic amino acid |

| Chirality | Achiral (only amino acid without optical activity) |

| Side Chain | Hydrogen (–H) |

| Solubility | Highly water-soluble |

| Special Feature | Found abundantly in collagen (every 3rd residue) |

Sources / Synthesis of Glycine

Glycine can be synthesized endogenously in several ways:

| Pathway | Enzyme | Cofactors | Location | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine → Glycine | SHMT | PLP, THF | Cytosol & mitochondria | Major contributor; linked to folate cycle |

| Threonine → Glycine | Threonine aldolase | PLP | Cytosol | Minor physiological source |

| Choline → Betaine → Glycine | Dimethylglycine dehydrogenase | FAD | Mitochondria | Connects methylation cycle |

| Glyoxylate → Glycine | AGT | PLP | Peroxisomes | Defects → Primary hyperoxaluria |

Cofactors:

-

Pyridoxal phosphate (Vitamin B₆)

-

Tetrahydrofolate (THF) for one-carbon transfer

Catabolism of Glycine

Metabolic Roles of Glycine

| Function | Compound Synthesized | Enzyme (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Heme synthesis | Glycine + Succinyl-CoA → δ-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA) | ALA synthase |

| Creatine synthesis | Glycine + Arginine → Guanidinoacetate → Creatine | Transamidase |

| Purine synthesis | Donates C₄, C₅, N₇ atoms of purine ring | — |

| Glutathione synthesis | Glycine + Cysteine + Glutamate → GSH | Glutathione synthetase |

| Bile salt conjugation | Bile acids + Glycine → Glycocholic acid, etc. | Bile acid–CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase |

| Porphyrin & Heme | As above | — |

| One-carbon metabolism | Forms CH₂-THF via glycine cleavage system | — |

Regulation of Glycine Metabolism

| Regulator | Effect on Metabolism | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PLP (Vitamin B6) | Required for SHMT, transaminases, ALA synthase | Deficiency ↓ glycine processing |

| Folate (THF) | Necessary for serine–glycine conversion | Folate deficiency disrupts 1-carbon metabolism |

| GCS Activity | Controls glycine degradation | Deficiency → NKH |

| Dietary Protein | ↑ glycine levels | Protein-rich foods boost supply |

| Hormones | Glucagon ↑ catabolism, Insulin ↑ anabolism | Affects amino acid turnover |

| Peroxisomal enzymes | Regulate glyoxylate handling | Defects → Hyperoxaluria |

Clinical Significance

| Disorder | Enzyme Defect / Cause | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Non-ketotic hyperglycinemia (glycine encephalopathy) | Defect in glycine cleavage enzyme complex | ↑ Glycine in CSF & plasma → severe neurological symptoms, seizures, mental retardation |

| Primary hyperoxaluria | Defective glyoxylate metabolism (↑ glyoxylate → oxalate) | Kidney stones, renal failure |

| Deficiency of THF or B₆ | Impaired glycine metabolism | Anemia, reduced one-carbon transfer reactions |

Laboratory Diagnosis

| Test | Sample | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma amino acid analysis | Blood | Detect elevated glycine |

| CSF amino acid profiling | CSF | Diagnose NKH |

| Urine oxalate measurement | Urine | Diagnose hyperoxaluria |

| Hippurate measurement | Urine | Evaluate detoxification function |

| HPLC / GC-MS | Plasma/Urine | Accurate quantitative analysis |

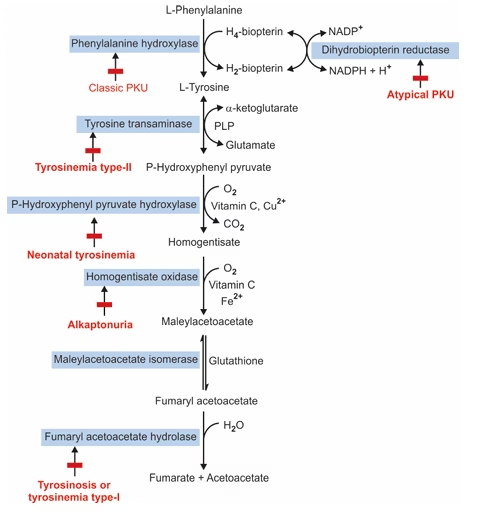

Metabolism of Phenylalanine and Tyrosine

Introduction

-

Phenylalanine (Phe) and Tyrosine (Tyr) are aromatic amino acids derived from the shikimate pathway in plants and obtained in humans from diet.

-

Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid, while tyrosine is non-essential (formed from phenylalanine).

-

Both are glucogenic and ketogenic.

-

They serve as precursors for several vital molecules — catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine), thyroid hormones, and melanin.

Conversion of Phenylalanine to Tyrosine:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Enzyme | Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) |

| Location | Liver |

| Cofactor | BH₄, Fe²⁺ |

| Importance | Prevents toxic buildup of phenylalanine |

| Defects | Cause Phenylketonuria (PKU) |

Reaction:Phenylalanine+O2+Tetrahydrobiopterin(BH4)→Tyrosine+H2O+Dihydrobiopterin(BH2)

Enzyme: Phenylalanine hydroxylase

Cofactors:

- Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH₄) – acts as a reducing cofactor

- Fe²⁺ (Iron) – required for enzyme activity

- Oxygen (O₂) – provides one atom for hydroxylation

Location: Liver cytosol

Mechanism:

- The enzyme adds a hydroxyl group (–OH) to the para position of the benzene ring of phenylalanine.

- This converts phenylalanine into tyrosine, making it hydroxylated at the 4th position (p-hydroxyphenylalanine).

- During the reaction, BH₄ is oxidized to BH₂ and later regenerated by dihydropteridine reductase using NADPH.

Significance:

- This is the first step in phenylalanine catabolism.

- It converts the essential amino acid (phenylalanine) into a non-essential amino acid (tyrosine).

- Tyrosine then serves as a precursor for melanin, catecholamines (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine), and thyroid hormones.

Clinical Importance:

- Deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase or BH₄ causes Phenylketonuria (PKU) → accumulation of phenylalanine and its toxic metabolites leading to mental retardation and hypopigmentation.

Regulation of Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Metabolism

| Regulation Type | Molecules Involved | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback inhibition | High tyrosine | Inhibits phenylalanine hydroxylase |

| Hormonal | Glucocorticoids | Induce tyrosine aminotransferase |

| Cofactor availability | BH₄, PLP, Vit C | Controls specific enzymes |

| Genetic | PAH, HGD, FAH mutations | Cause metabolic disorders |

Metabolic Disorders of Phenylalanine and Tyrosine

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism associated with the inability to convert phenylalanine to tyrosine. Ratio 1 in 20,000 newborns.

| Types | Condition | Enzyme defects |

| Type 1 | Classical type of PKU | Phenylalanine hydroxylase enzyme deficiency |

| Type 2 | Persistent hyperphenylalaninaemia | Phenylalanine hydroxylase enzyme deficiency |

| Type 3 | Transient mild hyperphenylalaninaemia | Phenylalanine hydroxylase enzyme is delayed |

| Type 4 | Dihydropterine reductase deficiency | Dihydropterine deficiency |

| Type 5 | Abnormal Dihydropterine function | Dihydropterine synthesis defects |

Tyrosinemia

There are three types of tyrosinemia:

- Tyrosinemia type-I (Tyrosinosis/Hepatorenal tyrosinemia)

- Tyrosinemia type-II (Richner-Hanhart syndrome)

- Neonatal tyrosinemia

Alkaptonuria

Definition: Alkaptonuria is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder characterized by the accumulation of homogentisic acid due to a deficiency in the enzyme homogentisate oxidase.

Enzyme Defect

- The defective enzyme in alkaptonuria is homogentisate oxidase in tyrosine metabolism.

- Homogentisate accumulates in tissues and blood and is excreted into urine. The urine of alkaptonuria patients resembles coke in colour.

Biochemical Manifestations

- Homogentisic Acid Accumulation:

- The main biochemical defect is the elevated levels of homogentisic acid in the body.

- This compound is toxic and can lead to various pathological effects.

- Urine Color Change:

- Urine from affected individuals darkens upon exposure to air due to the oxidation of homogentisic acid. This can happen within a few hours and is a hallmark feature of the disease.

- Freshly voided urine may appear normal but darkens rapidly when left standing.

- Ochronosis:

- Chronic accumulation of homogentisic acid can lead to tissue deposits in connective tissues, known as ochronosis.

- Common sites include the cartilage of joints, intervertebral discs, and the skin. This can cause discolouration and degenerative joint disease.

- Systemic Effects:

- Patients may experience early-onset arthritis, especially in large joints (e.g., hips, knees).

- Other complications include potential heart valve issues and kidney stones.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Evaluation:

- Diagnosis often starts with a clinical suspicion based on symptoms such as dark urine and joint pain.

- Urine Analysis:

- Colour Test: The darkening of urine upon standing is a critical diagnostic sign.

- Chemical Analysis: Urine can be tested for the presence of homogentisic acid using qualitative and quantitative methods, such as:

- HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography): Measures the levels of homogentisic acid.

- Spot Tests: A simple qualitative test where a few drops of urine can react with specific reagents to indicate the presence of homogentisic acid.

- Genetic Testing:

- Identification of mutations in the HGD gene can confirm the diagnosis.

- Genetic counselling may be recommended for affected individuals and their families.

Management

While there is currently no cure for alkaptonuria, management focuses on symptomatic relief and preventing complications:

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Encourage a balanced diet with limited intake of phenylalanine and tyrosine, although dietary restrictions may vary in severity based on individual cases.

- Maintain hydration to help reduce the risk of kidney stones.

- Pain Management:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used to manage joint pain.

- In severe cases, physical therapy or joint replacement surgery may be necessary.

- Monitoring:

- Regular followup to monitor joint health and function.

- Periodic assessment of urine for homogentisic acid levels can help gauge the condition’s progression.

- Research and Experimental Therapies:

- Ongoing research explores potential treatments, including enzyme replacement therapy and dietary supplements, but these are not yet standard practice.

Phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a genetic metabolic disorder caused by a defect in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH). This condition affects the body’s ability to metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine, leading to various biochemical and clinical manifestations.

Enzyme Defect

- Enzyme: Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH)

- Function: PAH catalyzes the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine, another amino acid.

- Deficiency: When PAH is deficient or absent, phenylalanine accumulates in the body, leading to toxic effects, particularly in the brain. The incidence of PKU is 1 in 10,000 births.

Biochemical Manifestations

- Elevated Phenylalanine Levels:

- The hallmark of PKU is significantly increased levels of phenylalanine in the blood (hyperphenylalaninemia).

- Normal phenylalanine levels are usually between 0.5 to 1.5 mg/dL, while levels in untreated PKU can exceed 20 mg/dL.

- Deficiency of Tyrosine:

- Since PAH converts phenylalanine to tyrosine, its deficiency leads to reduced levels of tyrosine, which is essential for neurotransmitter synthesis (dopamine, norepinephrine).

- Metabolite Accumulation:

- Increased phenylalanine can be converted to phenylpyruvate, which is then excreted in urine, along with other phenylalanine derivatives.

- Neurological Effects:

- High levels of phenylalanine are neurotoxic, leading to developmental delays, intellectual disability, seizures, and behavioural problems if untreated.

- Other Symptoms:

- Patients may develop lighter skin and hair due to reduced melanin production (tyrosine is a precursor for melanin).

Diagnosis

- Newborn screening:

- PKU is typically diagnosed through routine newborn screening programs that measure blood phenylalanine levels.

- A heel prick test is performed shortly after birth, usually within the first week.

- Blood Tests:

- Phenylalanine Levels: A blood sample is analyzed for elevated levels of phenylalanine. A level above the threshold indicates a risk for PKU.

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry: This advanced technique can confirm elevated phenylalanine and is often used in newborn screening.

- Genetic Testing:

- Confirmatory testing can involve genetic analysis to identify mutations in the PAH gene, confirming the diagnosis and subtype of PKU.

- This testing can also help assess the risk for family members.

- Clinical Evaluation:

- If PKU is suspected, a thorough clinical assessment will be conducted, looking for signs of neurological impairment or developmental delays.

Management

- Dietary Management:

- The cornerstone of PKU management is a strict, lifelong low-phenylalanine diet.

- Patients avoid high-protein foods (meat, fish, eggs, dairy, nuts) and certain grains.

- Special medical formulas that provide essential nutrients without phenylalanine are often used.

- Monitoring:

- Monitoring blood phenylalanine levels is crucial to ensure they remain within target ranges, typically below 6 mg/dL.

- Dietary adjustments may be necessary based on these levels.

- Supplementation:

- Tyrosine supplementation may be necessary due to its reduced levels in PKU patients.

- Emerging Therapies:

- New treatments, such as enzyme replacement therapy, pharmacological therapies (e.g., sapropterin dihydrochloride), and gene therapy, are being researched and may offer additional options.

- Support Services:

- Nutritional counselling and support groups can provide essential education and emotional support for families managing the condition.

Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD) is a rare genetic metabolic disorder caused by a defect in the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKAD) complex, which is essential for the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs): leucine, isoleucine, and valine.

Enzyme Defect

- Enzyme Complex: Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKAD) Complex

- Gene Mutations: Mutations can occur in several genes that encode components of the BCKAD complex, including:

- BCKDHA (alpha component)

- BCKDHB (beta component)

- DBT (dihydrolipoamide branched-chain transacylase)

- Function: The BCKAD complex catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of branched-chain alpha-keto acids derived from the BCAAs.

- Deficiency: When this complex is deficient, branched-chain amino acids accumulate and their corresponding alpha-keto acids in the blood and urine.

Biochemical Manifestations

- Elevated Branched-Chain Amino Acids:

- Blood levels of leucine, isoleucine, and valine become significantly elevated. Normal levels are typically below 150 μmol/L for leucine, 40 μmol/L for isoleucine, and 100 μmol/L for valine.

- In untreated MSUD, leucine levels can exceed 1,000 μmol/L.

- Accumulation of Alpha-Keto Acids:

- Alongside elevated BCAAs, their corresponding alpha-keto acids (such as alpha-ketoisocaproic acid) accumulate, which can be toxic, especially to the nervous system.

- Neurological Symptoms:

- Toxic levels of BCAAs and their metabolites can lead to neurological issues, including lethargy, seizures, and developmental delays.

- Urine Characteristics:

- The condition is named for the sweet, maple syrup-like odour of the urine due to the presence of branched-chain keto acids.

Diagnosis

- Newborn Screening:

- MSUD is typically diagnosed through routine newborn screening programs, which test for elevated levels of leucine and other BCAAs in dried blood spots collected shortly after birth.

- Clinical Presentation:

- Symptoms often appear within the first few days of life, including poor feeding, vomiting, lethargy, and irritability.

- Blood Tests:

- Confirmatory blood tests measure the levels of branched-chain amino acids, showing significant elevations of leucine, isoleucine, and valine.

- Urine Analysis:

- Urinalysis may reveal the presence of branched-chain keto acids, which specific chemical tests can detect.

- Genetic Testing:

- Genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis by identifying mutations in the genes associated with the BCKAD complex.

- This testing can also help determine the specific subtype of MSUD, as there are several variants (classic, intermediate, and thiamine-responsive).

Management

- Dietary Management:

- The primary treatment for MSUD involves a strict diet low in branched-chain amino acids, particularly leucine.

- Special medical formulas that provide essential amino acids without BCAAs are essential for growth and development.

- Monitoring:

- Regularly monitoring blood amino acid levels is crucial to prevent toxic accumulation and adjust dietary intake as needed.

- Emergency Protocols:

- In times of illness or stress, rapid intervention may be required to manage acute metabolic crises, which can be life-threatening. This often involves hospitalization and intravenous fluids.

- Potential Therapies:

- Research is ongoing into new treatments, including enzyme replacement therapy, gene therapy, and alternative dietary strategies.

- Support Services:

- Nutritional counselling and family support resources are vital for managing the condition effectively.

Albinism

Albinism is a group of genetic disorders characterized by a deficiency or absence of melanin production in the skin, hair, and eyes. The condition arises from defects in specific enzymes involved in the melanin biosynthesis pathway.

Enzyme Defect

- Common Enzyme Defects:

- Tyrosinase: The most common defect occurs in tyrosinase, which catalyzes the conversion of tyrosine to DOPA (dihydroxyphenylalanine) and then to dopaquinone, a melanin precursor. This is associated with Oculocutaneous Albinism Type 1 (OCA1).

- Other Enzymes: Defects in other enzymes like tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1) and Dopachrome tautomerase (DCT) lead to other forms of albinism.

- Gene Mutations:

- TYR (tyrosinase gene), OCA2 (associated with OCA2), and TYRP1 genes are among the most frequently mutated genes in different types of albinism.

Biochemical Manifestations

- Reduced Melanin Production:

- Affected individuals have significantly reduced or absent melanin levels in the skin, hair, and eyes.

- The lack of melanin leads to lighter pigmentation and can result in white or light-coloured hair and skin.

- Ocular Abnormalities:

Common ocular manifestations include:

-

- Nystagmus: Involuntary eye movements.

- Strabismus: Misalignment of the eyes.

- Photophobia: Sensitivity to bright light.

- Reduced Visual Acuity: Impaired vision due to improper retina development.

3. Increased Sun Sensitivity:

-

- Individuals with albinism are more susceptible to sunburn and skin damage due to the lack of protective melanin.

- They have a higher risk of developing skin cancers, including melanoma.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Evaluation:

- Diagnosis often begins with a clinical examination that reveals characteristic features such as light skin, hair, eye colour, and ocular abnormalities.

- Family History:

- A family history of albinism can support the diagnosis, as many forms are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

- Genetic Testing:

- Molecular genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis by identifying mutations in the relevant genes.

- This testing can also help determine the specific type of albinism.

- Ophthalmologic Examination:

- A detailed eye examination can reveal specific ocular defects associated with albinism, such as foveal hypoplasia (underdevelopment of the fovea) and abnormal retinal structure.

- Skin Biopsy:

- Sometimes, a skin biopsy may be performed to assess melanin production and distribution.

Management

- Sun Protection:

- Individuals with albinism should take strict measures to protect their skin from UV exposure, including high-SPF sunscreen, protective clothing, and sunglasses.

- Vision Support:

- Visual aids and corrective lenses may be necessary to improve visual acuity.

- Regular eye exams are essential for monitoring and addressing ocular issues.

- Educational Support:

- Specialized educational resources may be required to accommodate visual impairments.

- Psychosocial Support:

- Counselling and support groups can help individuals and families cope with the challenges associated with living with albinism, including social stigma and psychological impacts.

Hartnup disorder

Hartnup disorder is a rare genetic condition characterized by the impaired absorption of certain amino acids, primarily neutral ones, in the kidneys and intestines. A defect in a specific transporter protein causes this disorder.

Enzyme Defect

- Transporter Defect: The primary defect in Hartnup disorder is in the gene, which encodes a sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter.

- Affected Transport: This transporter reabsorbs neutral amino acids (such as tryptophan, leucine, isoleucine, and phenylalanine) in the renal tubules and the intestines.

Biochemical Manifestations

- Amino Aciduria:

- Due to the defective transporter, neutral amino acids are not effectively reabsorbed, leading to excessive urine loss (aminoaciduria).

- This results in low blood levels of these amino acids (hypoaminoacidemia).

- Tryptophan Deficiency:

- The loss of tryptophan can lead to decreased serotonin and niacin (vitamin B3) synthesis, as tryptophan is a precursor for both.

- Niacin deficiency can result in symptoms similar to pellagra, including diarrhoea, dermatitis, and dementia.

- Neurological Symptoms:

- Some individuals may experience neurological issues due to low levels of neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin) derived from tryptophan. Symptoms can include ataxia, psychiatric disturbances, and mood changes.

- Skin Manifestations:

- Some patients may develop photosensitivity and skin rashes, especially when exposed to sunlight, due to the effects of tryptophan deficiency and niacin deficiency.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Evaluation:

- Diagnosis often begins with a clinical assessment of photosensitivity, ataxia, and neurological manifestations.

- Family history may provide additional context, as Hartnup disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

- Urine Analysis:

- A 24-hour urine collection can reveal elevated levels of neutral amino acids, particularly tryptophan, leucine, and isoleucine.

- Blood Tests:

- Blood tests may show low levels of neutral amino acids, especially tryptophan.

- Genetic Testing:

- Molecular genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis by identifying mutations in the SLC6A19

- Genetic counselling may be recommended for affected individuals and their families.

- Response to Niacin Supplementation:

- Sometimes, a trial of niacin supplementation can help assess the impact of the deficiency on symptoms and provide supportive evidence for the diagnosis.

Management

- Dietary Management:

- A balanced diet rich in proteins and potentially supplemented with essential amino acids may help manage symptoms.

- Some individuals may benefit from a niacin-rich diet or supplementation to prevent deficiency.

- Symptomatic Treatment:

- Addressing specific symptoms, such as skin rashes or neurological issues, may require additional treatment and support.

- Sun Protection:

- Patients may need to avoid excessive sun exposure and use sunscreen to manage photosensitivity.

- Regular Monitoring:

- Regular follow-ups with healthcare providers are important to monitor amino acid levels and overall health.

MCQs

1. The first step in dietary protein digestion begins in the:

A. Mouth

B. Stomach

C. Duodenum

D. Ileum

2. The major proteolytic enzyme of the stomach is:

A. Trypsin

B. Pepsin

C. Chymotrypsin

D. Elastase

3. Pepsinogen is activated to pepsin by:

A. Trypsin

B. HCl

C. Secretin

D. Bicarbonate

4. Enteropeptidase converts:

A. Trypsin to trypsinogen

B. Trypsinogen to trypsin

C. Pepsinogen to pepsin

D. Proelastase to elastase

5. The major site of amino acid absorption is:

A. Stomach

B. Duodenum

C. Jejunum

D. Colon

6. Amino acids are absorbed by:

A. Primary active transport

B. Secondary active transport

C. Diffusion

D. Facilitated diffusion

7. Transamination requires which coenzyme?

A. NAD⁺

B. PLP (Vitamin B6)

C. Biotin

D. THF

8. The major enzyme for removing the amino group from glutamate is:

A. ALT

B. AST

C. Glutamate dehydrogenase

D. Transaminase

9. Glutamate dehydrogenase uses which cofactors?

A. NAD⁺ or NADP⁺

B. FAD

C. THF

D. PLP

10. Urea cycle occurs primarily in the:

A. Brain

B. Kidney

C. Liver

D. Intestine

11. The first amino acid used in urea cycle is:

A. Glycine

B. Glutamine

C. Arginine

D. Ammonia

12. Carbamoyl phosphate synthase I is located in:

A. Cytosol

B. Mitochondria

C. ER

D. Nucleus

13. The rate-limiting enzyme of urea cycle is:

A. Arginase

B. CPS-I

C. ASS

D. ASL

14. CPS-I requires which activator?

A. Glutamate

B. Aspartate

C. N-Acetylglutamate

D. Fumarate

15. Ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency leads to:

A. Hyperglycinemia

B. Hyperammonemia

C. Maple syrup urine disease

D. Hartnup disease

16. In the liver, ammonia is converted to:

A. Uric acid

B. Creatinine

C. Urea

D. Glucose

17. During prolonged fasting, major gluconeogenic amino acid is:

A. Phenylalanine

B. Leucine

C. Alanine

D. Tryptophan

18. Glucogenic amino acids produce:

A. Acetoacetate

B. Acetyl-CoA

C. TCA cycle intermediates

D. Fatty acids

19. Ketogenic amino acids include:

A. Leucine & Lysine

B. Alanine & Glycine

C. Valine & Proline

D. Histidine & Arginine

20. Which amino acid forms serotonin?

A. Tyrosine

B. Tryptophan

C. Phenylalanine

D. Histidine

21. Phenylalanine hydroxylase requires:

A. Biotin

B. THF

C. BH4

D. PLP

22. Transamination of alanine produces:

A. Acetyl-CoA

B. Pyruvate

C. Oxaloacetate

D. α-Ketoglutarate

23. Glutamine serves as a major carrier of:

A. Hydrogen ions

B. CO₂

C. Ammonia

D. Uric acid

24. Cystinuria is caused by defective transport of:

A. Neutral amino acids

B. Acidic amino acids

C. Basic amino acids & cystine

D. Aromatic amino acids

25. Maple syrup urine disease involves defect in metabolism of:

A. Aromatic amino acids

B. Sulfur-containing amino acids

C. Branched-chain amino acids

D. Acidic amino acids

26. Alkaptonuria is due to defect in:

A. Phenylalanine hydroxylase

B. Homogentisate oxidase

C. Tyrosinase

D. DOPA decarboxylase

27. Phenylketonuria results from deficiency of:

A. BH2

B. CPS-I

C. Phenylalanine hydroxylase

D. Tryptophan hydroxylase

28. Carbamoyl phosphate is formed from:

A. CO₂ + NH₃ + ATP

B. CO₂ + H₂O + ATP

C. Glutamine + ATP

D. Urea + ATP

29. The step in urea cycle that releases urea is catalyzed by:

A. ASS

B. ASL

C. CPS-I

D. Arginase

30. Fumarate formed in urea cycle enters:

A. Glycolysis

B. TCA cycle

C. PPP

D. FA synthesis

31. Nitrogen balance is positive in:

A. Illness

B. Fasting

C. Growth & pregnancy

D. Burns

32. Kwashiorkor is characterized by:

A. Edema

B. Muscle wasting only

C. No fatty liver

D. Low insulin

33. Marasmus is characterized by:

A. Edema

B. Severe wasting

C. Fatty liver

D. Hypoalbuminemia only

34. During starvation, muscle releases:

A. Leucine and lysine

B. Alanine and glutamine

C. Phenylalanine and tyrosine

D. Methionine and cysteine

35. The major amino acid for ammonium trapping in the kidney is:

A. Alanine

B. Glycine

C. Glutamine

D. Serine

36. Essential amino acids are:

A. Alanine, glycine, serine

B. Leucine, valine, lysine

C. Tyrosine, cysteine

D. Proline, arginine in adults

37. Tyrosine is synthesized from:

A. Leucine

B. Glycine

C. Phenylalanine

D. Valine

38. Dopa decarboxylase requires:

A. PLP

B. THF

C. Biotin

D. FAD

39. Amino acids important for one-carbon metabolism include:

A. Glycine & serine

B. Leucine & tryptophan

C. Tyrosine & phenylalanine

D. Arginine & lysine

40. Homocysteine is formed from:

A. Serine

B. Methionine

C. Lysine

D. Glycine

41. SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) is:

A. Methyl donor

B. Biotin carrier

C. Antioxidant

D. Precursor of urea

42. Creatine is synthesized from:

A. Glycine + Arginine

B. Glycine + Lysine

C. Methionine + Tyrosine

D. Alanine + Glutamine

43. Major amino acid in collagen is:

A. Valine

B. Serine

C. Glycine

D. Glutamate

44. Hydroxylation of proline requires:

A. Vit B6

B. Vit C

C. Vit K

D. FAD

45. Nitric oxide is formed from:

A. Glycine

B. Arginine

C. Proline

D. Serine

46. GABA is synthesized from:

A. Tyrosine

B. Serine

C. Glutamate

D. Glycine

47. Which amino acid is purely ketogenic?

A. Isoleucine

B. Phenylalanine

C. Tyrosine

D. Leucine

48. Glucose-alanine cycle transfers:

A. CO₂

B. Ammonia to liver

C. Ketones

D. Fatty acids

49. Which amino acid forms histamine?

A. Histidine

B. Arginine

C. Tryptophan

D. Tyrosine

50. Rate of protein turnover is highest in:

A. Bone

B. Skin

C. Intestinal mucosa

D. Muscle

✅ ANSWER KEY

1-B

2-B

3-B

4-B

5-C

6-B

7-B

8-C

9-A

10-C

11-D

12-B

13-B

14-C

15-B

16-C

17-C

18-C

19-A

20-B

21-C

22-B

23-C

24-C

25-C

26-B

27-C

28-A

29-D

30-B

31-C

32-A

33-B

34-B

35-C

36-B

37-C

38-A

39-A

40-B

41-A

42-A

43-C

44-B

45-B

46-C

47-D

48-B

49-A

50-C