Introduction

- Serological and immunological techniques are laboratory-based methods used to detect and measure the presence of specific antigens (substances that provoke an immune response) or antibodies (proteins produced by the immune system in response to an antigen) in a sample.

- These methods are crucial in diagnosing infectious diseases, autoimmune conditions, and other immune-related disorders.

- Techniques such as Gel Diffusion (THFA), Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA), ELISA, and Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) are widely used to identify infections by detecting the interaction between antigens and antibodies.

- These techniques offer distinct advantages regarding sensitivity, specificity, and versatility for diagnosing various diseases.

Gel Diffusion (THFA)

- Gel diffusion is a type of immunodiffusion technique used to detect the presence of antibodies or antigens in a sample.

- This technique involves the movement of antigens and antibodies in a gel medium to create visible precipitates when they meet at optimal concentrations, indicating the presence of specific immune complexes.

- The Thick-Half-Floating Agarose (THFA) method is a type of gel diffusion used for detecting specific antigens or antibodies.

- The method utilizes a gel matrix (typically agarose) and takes advantage of the fact that antigens and antibodies will diffuse through the gel at different rates, creating areas where they react to form precipitates.

Principle

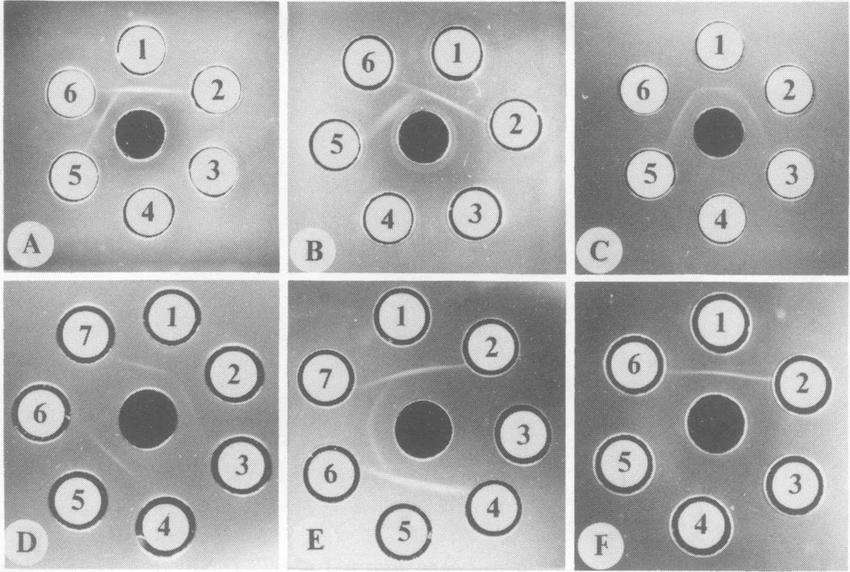

The principle of gel diffusion is based on the diffusion of both antigens and antibodies within an agarose gel. When both meet at an optimal concentration, they form a visible precipitate due to antigen-antibody interaction. This reaction occurs when the antigen and antibody form insoluble immune complexes in the gel, leading to precipitation.

-

Antigen and Antibody Diffusion: The antigen and antibody are placed in separate wells within a gel medium in gel diffusion assays. When the two components diffuse toward each other, they form a visible precipitate where they meet in the gel.

-

Precipitation Zone: The formation of this precipitate is the key indicator of a positive reaction. The precipitate forms when the antigen and antibody combine in a specific ratio to form a stable immune complex.

-

Gel Matrix: The gel serves as a medium through which the antigen and antibody diffuse. The gel is typically made of agarose, a solidifying agent that allows for easy diffusion and the formation of clear precipitates.

-

Conditions for Precipitation: Precipitation occurs at the optimal concentration of antigen and antibody, and the strength of the precipitate is dependent on the amount of antigen-antibody interaction.

Procedure

- Preparation of Agarose Gel:

- An agarose gel is prepared by mixing agarose with a buffer solution to provide the medium for diffusion. The gel is poured into a petri dish or a suitable container, and it is allowed to solidify.

- Wells Formation:

- Once the gel is solidified, wells are made using a punching tool, and the wells are carefully arranged in the gel to place the antigen and antibody solutions.

- Antigen and Antibody Loading:

- In a typical THFA test, an antigen solution (containing the substance that will be tested for antibody presence) is placed in one well, while the patient’s serum (or known antibody solution) is placed in the adjacent well. The wells should be placed at an optimal distance for diffusion.

- Incubation:

- The gel is incubated under appropriate conditions, usually at room temperature or in a controlled environment. During this time, the antigen and antibody will diffuse through the gel and eventually meet at the optimal concentration to form a visible precipitate.

- Precipitate Formation:

- If the antigen in the test sample reacts with the antibody in the well, a visible precipitate forms in the region of the gel where the antigen and antibody meet. The precipitate indicates the presence of a specific immune response in the sample.

- Results Interpretation:

- The appearance of a clear line or zone of precipitation between the wells indicates a positive result. The intensity or thickness of the precipitate can be used to estimate the quantity of the antigen or antibody present in the sample.

Advantages

-

Simplicity:

- Gel diffusion techniques are relatively simple and easy to perform compared to more complex immunoassays like ELISA or PCR. The setup is inexpensive and requires minimal specialized equipment.

-

Cost-Effective:

- This inexpensive method requires minimal reagents and resources, making it suitable for resource-limited settings or laboratories.

-

Direct Visualization:

- The formation of a visible precipitate provides direct visual evidence of an antigen-antibody reaction. This makes the results easy to interpret without the need for specialized equipment.

-

Qualitative Results:

- Gel diffusion is useful for providing qualitative data, especially when there is a need to confirm the presence or absence of a specific antibody or antigen.

-

Suitable for Multiple Samples:

- The agarose gel can accommodate multiple wells, meaning multiple tests can be conducted simultaneously, making it useful for screening large samples.

Disadvantages

-

Slow Results:

- The diffusion process takes time, typically several hours or overnight, to achieve optimal results. This makes it slower than other techniques, such as lateral flow immunoassays or ELISA.

-

Limited Quantification:

- Although gel diffusion can demonstrate the presence of antigen-antibody interactions, it does not provide precise quantification of the antigen or antibody levels. The amount of precipitate may indicate the presence of an immune response but not the exact concentration.

-

Subjectivity in Interpretation:

- The formation of a precipitate depends on the optimal antigen-antibody ratio. Variations in the gel’s composition or well spacing may result in weak or faint precipitates, which can be difficult to interpret, especially in borderline cases.

-

Cross-Reactivity:

- Cross-reactivity is possible, where antibodies in the sample might bind to antigens that are similar but not identical to the target antigen, leading to false positives.

-

Complex Samples:

- The presence of complex mixtures or interfering substances in the sample may make it difficult to interpret results. For example, high concentrations of non-specific proteins or other substances in the serum can affect diffusion.

Limitations

-

Requires Proper Handling:

- The technique requires careful gel handling and proper formation of wells to ensure optimal diffusion conditions. Improper handling may lead to inconsistent results or incomplete diffusion.

-

Inability to Detect Low Concentrations:

- While gel diffusion is good for detecting the presence of antigens or antibodies, it may not be sensitive enough to detect very low concentrations of the target molecules, making it unsuitable for early detection of some diseases.

-

Potential for False Negatives:

- False negatives may occur if the antigen and antibody do not meet at the optimal concentration for precipitation. This could happen due to improper well spacing or low amounts of the antigen or antibody in the sample.

-

Limited to Specific Applications:

- Gel diffusion is not suitable for detecting all types of antigens or antibodies. It is typically used in applications where precipitation is a reliable marker, such as identifying immune complexes, but it may not be as useful for detecting soluble antigens or antibodies in more complex samples.

Applications

-

Infectious Disease Diagnosis:

- Gel diffusion (THFA) is widely used in diagnosing infectious diseases, particularly for detecting the presence of specific antibodies or antigens in the serum. It is commonly used for testing conditions such as:

- Tuberculosis (TB): Detecting antibodies against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Leptospirosis: Identifying antibodies against Leptospira bacteria.

- Brucellosis: Testing for antibodies against Brucella bacteria.

- Gel diffusion (THFA) is widely used in diagnosing infectious diseases, particularly for detecting the presence of specific antibodies or antigens in the serum. It is commonly used for testing conditions such as:

-

Autoimmune Disease Diagnosis:

- Gel diffusion (THFA) can be used to detect autoantibodies in diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

-

Research:

- In research laboratories, gel diffusion is used to study antigen-antibody reactions, understand immune responses, and identify specific antibodies related to infectious agents.

-

Allergy Testing:

- Gel diffusion can also be used in allergy testing by detecting the presence of IgE antibodies specific to various allergens.

Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) Test

- The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) test is a widely used technique in immunology for detecting specific antibodies in a patient’s serum.

- It is particularly valuable in diagnosing infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, and certain cancers.

- The test uses a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody to detect the binding of a primary antibody to a specific antigen, and it is most commonly employed in detecting antigens in cells or tissues.

Principle

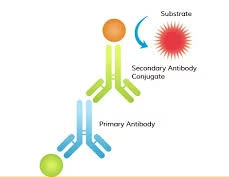

The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) test is based on the antigen-antibody binding reaction. It involves using a fluorescent dye (such as fluorescein isothiocyanate, FITC) conjugated to a secondary antibody, which binds to the primary antibody. The principle can be outlined as follows:

-

Antigen Coating: A target antigen (such as a virus, bacterium, or other disease-related antigen) is immobilized on a slide or a surface. This can be done using infected tissue, cultured cells, or purified proteins. The antigen could be associated with the surface of cells or fixed tissue sections.

-

Primary Antibody Addition: The patient’s serum may contain the specific antibody against the antigen, which is added to the antigen-coated surface. If the patient’s serum contains antibodies specific to the antigen, the antibodies will bind to the antigen.

-

Binding of Secondary Antibody: After washing off unbound serum, a secondary antibody conjugated to a fluorescent dye (such as FITC) is added. This secondary antibody specifically binds to the primary antibody.

-

Fluorescence Detection: The slide is examined under a fluorescence microscope. When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, the secondary antibody emits fluorescence, and the presence and intensity of the fluorescence indicate the presence and amount of primary antibody bound to the antigen.

Procedure

-

Preparation of Antigen: The antigen of interest (e.g., viral particles or bacterial components) is fixed on a glass slide. This may involve preparing infected cells, tissue sections, or purified antigens, which are then immobilized on the surface.

-

Addition of Patient Serum: The patient’s serum is added to the slide. If the serum contains the specific antibody, it will bind to the antigen on the slide. The incubation period for this binding step may range from 30 minutes to an hour.

-

Washing: After incubation, the slide is washed thoroughly to remove any unbound serum proteins or antibodies, leaving only the antibody-antigen complexes.

-

Fluorescently-Labeled Secondary Antibody: The secondary antibody, which is labeled with a fluorescent dye (such as FITC), is applied. This antibody binds specifically to the primary antibody already bound to the antigen.

-

Washing and Drying: Excess secondary antibody is washed off, and the slide is dried.

-

Microscopic Examination: The slide is placed under a fluorescence microscope. When exposed to UV light, the secondary antibody emits fluorescence. The presence and intensity of this fluorescence are used to assess the presence and amount of the target antibody in the sample.

Advantages

-

High Sensitivity: IFA is very sensitive because it uses an indirect method with a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody, which amplifies the signal and detects low antibody concentrations.

-

Specificity: The use of primary and secondary antibodies specific to the antigen and human immunoglobulins ensures that only the correct antibody-antigen interactions are detected.

-

Direct Visualization: The ability to visualize the binding of the antibody to the antigen under a fluorescence microscope allows for qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment.

-

Versatility: IFA can detect various pathogens (viruses, bacteria, fungi) and antibodies in autoimmune diseases. It is also useful for detecting antibodies in the diagnosis of parasitic infections.

-

Research Applications: IFA is widely used in research for studying protein localization within cells or tissues, which helps understand the cellular mechanisms and the interactions between different biological molecules.

Disadvantages

-

Requires Specialized Equipment: The test requires a fluorescence microscope for detecting the fluorescent signal, which may not be available in all laboratories, especially in resource-limited settings.

-

Subjective Interpretation: The results of an IFA test can be somewhat subjective, depending on the operator’s skill and the quality of the fluorescence. Misinterpretation can lead to false-positive or false-negative results.

-

Time-Consuming: The IFA test requires multiple incubation and washing steps, which may take several hours, making it less suitable for rapid testing in emergency situations.

-

Cross-Reactivity: The secondary antibody could bind to other immunoglobulins in the serum, leading to non-specific fluorescence and false-positive results. Cross-reactivity between closely related antigens can also complicate results.

-

False Positives: The presence of non-specific binding or contamination of the sample could lead to false positives. Also, the secondary antibody may bind to other serum proteins, leading to background fluorescence.

Limitations

-

Interpretation Skills Required: Reading and interpreting the results requires a trained eye, as the fluorescence intensity can vary, and distinguishing between background fluorescence and true positive results can be challenging.

-

False Negatives: If the antigen concentration is too low or if the antibody in the serum is present in low titers, the test may not show sufficient fluorescence, leading to a false-negative result.

-

Limited Quantification: While IFA can provide a semi-quantitative result based on fluorescence intensity, it is not as precise or reliable as other methods like ELISA in quantifying antibody levels.

-

False Positives from Cross-Reactivity: Cross-reactivity between antibodies from different pathogens or other substances in the serum can lead to false-positive results, especially in patients with previous infections or vaccinations.

Applications

-

Infectious Disease Diagnosis:

- Viral Infections: IFA is widely used to detect antibodies against viruses such as Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and others.

- Bacterial Infections: It is used to identify antibodies against bacteria like Rickettsia, Chlamydia, and Leptospira.

- Parasitic Infections: IFA detects antibodies against parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium (malaria).

-

Autoimmune Diseases:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): IFA is commonly used to detect antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in diagnosing SLE.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: It can detect rheumatoid factor (RF) and other related autoantibodies.

- Other Autoimmune Conditions: IFA is also used to diagnose conditions like Sjögren’s syndrome, autoimmune thyroiditis, and more.

-

Cancer Diagnosis: IFA is used in some cancers to detect tumour markers and antibodies related to specific cancers.

-

Research Applications: IFA is an essential tool in research to study the localization of antigens and antibodies in cell cultures or tissue samples. It allows researchers to observe antigen distribution within cells or tissues and to investigate the immune response to infections or vaccinations.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is one of the most widely used techniques in immunology and diagnostics for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as proteins, hormones, antibodies, and antigens. It is used in various industries’ clinical diagnostics, research, and quality control.

Principle

The core principle of ELISA is the specific binding of antibodies to antigens. The method relies on an enzyme conjugated to an antibody or antigen, which catalyzes a substrate reaction to produce a detectable signal, typically a colour change. The colour change is proportional to the amount of the target antigen or antibody in the sample.

There are several types of ELISA, including:

- Direct ELISA – The antigen is bound to the plate, and an enzyme-conjugated antibody is added to bind the antigen.

- Indirect ELISA – The antigen is bound to the plate, and a primary antibody is added, followed by a secondary antibody conjugated with an enzyme.

- Sandwich ELISA – The antigen is “sandwiched” between two antibodies, typically a capture antibody and a detection antibody, with an enzyme conjugated to the detection antibody.

- Competitive ELISA – The antigen competes with a labelled antigen for binding sites on the antibody.

Procedure

The general procedure for performing an ELISA test typically involves the following steps:

-

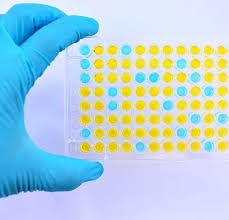

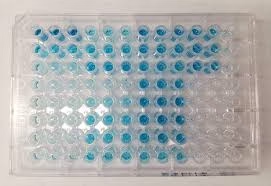

Coating the Plate: The first step is to coat a microplate (usually 96-well) with the antigen or antibody of interest. The plate is coated with an antibody that will capture the antigen from the sample for antigen detection. The plate is coated with the antigen that will bind to the antibodies in the sample for antibody detection.

-

Blocking: After immobilising the antigen or antibody, any remaining uncoated areas on the plate are blocked with a blocking buffer (such as Bovine Serum Albumin or non-fat milk). This step prevents non-specific binding in later steps.

-

Sample Addition: The patient’s sample (which may contain the target antigen or antibody) is added to the wells of the microplate. If the target is present in the sample, it will bind to the immobilized antigen or antibody.

-

Washing: The plate is washed to remove any unbound substances, ensuring that only specifically bound antigen-antibody complexes remain.

-

Addition of Enzyme-Conjugated Antibody: A secondary antibody conjugated to an enzyme (such as horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase) is added after washing. This antibody binds to the antigen-antibody complex formed earlier. In the case of a sandwich ELISA, the detection antibody is used for this purpose.

-

Substrate Addition: A substrate is added after washing off excess secondary antibodies. The enzyme reacts with the substrate to produce a detectable signal, often a colour change. The intensity of the colour change is directly proportional to the amount of target antigen or antibody in the sample.

-

Measurement: The colour change is quantified by measuring the absorbance using a spectrophotometer or plate reader. The absorbance values (optical density, OD) are used to calculate the target concentration in the sample.

Advantages

-

High Sensitivity: ELISA is highly sensitive and capable of detecting low levels of antigens or antibodies, which is useful for early detection of diseases or low-concentration targets.

-

Quantitative Results: Unlike some other immunological assays, ELISA provides quantitative results. The colour change’s optical density (OD) can be directly correlated to the target concentration in the sample.

-

Wide Range of Applications: ELISA can be used for a broad range of applications, including diagnosing infections, measuring hormone levels, detecting allergens, and assessing immune responses.

-

High Throughput: ELISA allows for testing multiple samples at once, making it ideal for large-scale screenings or research studies.

-

Relatively Simple: While it requires specific reagents and equipment, the basic procedure is straightforward and does not require complex instrumentation or highly specialized personnel.

-

Cost-Effective: Compared to more sophisticated techniques like PCR or Western blotting, ELISA is a relatively cost-effective method for diagnostic and research purposes.

Disadvantages

-

Requires Equipment: ELISA requires a plate reader or spectrophotometer to measure absorbance, which adds to the cost and equipment requirements.

-

Time-Consuming: While not as labour-intensive as some methods, ELISA can take several hours due to multiple washing and incubation steps.

-

Cross-Reactivity: Similar substances in the sample may cause cross-reactivity, leading to false positives or inaccurate results. For example, antibodies may cross-react with other antigens, especially in complex samples.

-

False Results due to Interference: Certain components in the sample, such as high levels of lipids or other interfering substances, can affect the accuracy of the assay.

-

Not Ideal for Very Complex Samples: While ELISA is powerful, it is less effective when testing very complex or heterogeneous samples where interference may affect the results.

Limitations

-

Non-Specific Binding: While blocking helps, there is always a potential for non-specific binding of other molecules to the plate, which can lead to false positives or inaccurate measurements.

-

Dependence on Good Antibodies: The accuracy and sensitivity of ELISA heavily depend on the antibodies’ quality. Poor-quality antibodies can result in weak or non-specific binding.

-

Quantification Limitations: While ELISA provides quantitative results, it is generally not as precise as other techniques like mass spectrometry when exact quantification of a molecule is required.

-

Interference from Sample Matrix: Some biological samples, such as serum, plasma, or urine, contain substances that can interfere with the assay. For example, high protein concentrations can affect enzyme activity or the ability of the substrate to react, leading to inaccurate results.

-

Antigen Availability: In some cases, obtaining or preparing pure and stable antigens to coat the plate may be challenging, especially for pathogens or rare proteins.

Applications

ELISA is used extensively across various fields for both research and diagnostic purposes:

-

Infectious Disease Diagnostics:

- HIV/AIDS: Detects antibodies against the HIV virus.

- Hepatitis B and C: Identifies antibodies or antigens for these viruses.

- COVID-19: Used to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in response to infection or vaccination.

-

Hormone and Protein Quantification: ELISA can measure levels of hormones (such as insulin, cortisol, and thyroid hormones) and other proteins (e.g., cytokines and growth factors) in the blood.

-

Allergen Testing: ELISA tests for specific antibodies against common allergens, such as dust mites, pollen, or food proteins.

-

Autoimmune Disease Diagnosis: ELISA can detect autoantibodies, such as those in lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or autoimmune thyroid diseases.

-

Cancer Biomarkers: ELISA is used to detect and quantify cancer-related biomarkers (e.g., prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer).

-

Drug Testing: In the pharmaceutical and clinical settings, ELISA can test for drugs or metabolites in urine, blood, or serum.

-

Veterinary Medicine: ELISA is also applied in animal diagnostics to detect infections, antibodies, or animal antigens.

Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) Test

The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) test is a sensitive and widely used technique in immunology for detecting antibodies against specific antigens in a patient’s sample (such as serum). It is particularly useful for diagnosing infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites, and autoimmune conditions.

Principle

The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) test is based on the principle of antigen-antibody binding, which is detected using a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody. This method involves the following key components:

- Antigen Immobilization: The specific antigen (such as viral or bacterial proteins) is immobilized on a slide or a surface.

- Primary Antibody Binding: The patient’s serum (which may contain the target antibody) is added to the antigen-coated slide. If the patient’s serum contains specific antibodies to the antigen, these antibodies will bind to the immobilized antigen.

- Fluorescently Labeled Secondary Antibody: A secondary antibody conjugated to a fluorescent dye (commonly fluorescein or rhodamine) is added. This secondary antibody specifically binds to the primary antibody in the patient’s serum.

- Fluorescence Detection: The slide is examined under a fluorescence microscope after washing off excess secondary antibodies. If the primary antibody has bound to the antigen, the secondary antibody will emit fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. This fluorescence is the key indicator of a positive reaction.

Procedure

- Preparation of Antigen: The antigen (from a pathogen or target protein) is prepared and fixed onto a glass slide. The antigen may be derived from infected tissue, cultured cells, or recombinant proteins.

- Incubation with Patient Serum: The patient’s serum is applied to the antigen-coated slide. If the serum contains antibodies that recognize the antigen, they will bind to it during incubation.

- Washing: The slide is thoroughly washed to remove unbound serum proteins or antibodies.

- Addition of Secondary Fluorescently Labeled Antibody: A secondary antibody conjugated with a fluorescent dye (such as fluorescein or rhodamine) is added. This antibody binds to the patient’s primary antibody.

- Final Washing: Excess secondary antibodies are removed through washing.

- Examination under Fluorescence Microscope: The slide is examined under a fluorescence microscope. If the primary antibody is bound to the antigen, the secondary antibody will emit fluorescence. The fluorescence’s presence and intensity indicate the antibody’s presence in the patient’s serum.

Advantages

- High Sensitivity: The indirect approach of using a fluorescent secondary antibody amplifies the signal, making the IFA highly sensitive. It can detect even low concentrations of antibodies.

- Specificity: IFA is highly specific, as it relies on binding the primary antibody to the target antigen, and using a secondary antibody specific to human immunoglobulins further enhances this specificity.

- Visual Detection: The test allows for direct visualization of the antigen-antibody interaction under the microscope, which can help determine the antigen’s localisation within tissues or cells.

- Versatility: It can detect antibodies against various pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, and is also employed in diagnosing autoimmune diseases.

Disadvantages

- Specialized Equipment: IFA requires a fluorescence microscope to detect the fluorescent signal, which can be expensive and unavailable in all laboratories.

- Subjective Interpretation: Interpretation of results requires expertise in fluorescence microscopy. The intensity of the fluorescence may be subtle and can sometimes lead to false positives or negatives.

- Time-Consuming: The procedure involves multiple incubation and washing steps, which can make the process relatively slow.

- Cross-Reactivity: The secondary antibody can sometimes bind to other immunoglobulins, leading to non-specific fluorescence and potential false-positive results.

- Cost: Fluorescent reagents and specialized equipment contribute to this test’s higher cost than simpler techniques.

Limitations

- Requires Expertise: The procedure and result interpretation require highly trained personnel to identify and assess fluorescence correctly. Poor handling or misinterpretation can lead to erroneous conclusions.

- Limited by Antigen Availability: In some cases, obtaining or preparing a pure and stable antigen for coating on slides may be difficult, limiting the use of the test for certain pathogens or conditions.

- False Positives from Cross-Reactivity: The fluorescent secondary antibody may sometimes bind to other antibodies in the serum, causing cross-reactivity and potentially leading to false-positive results.

- Quantification Challenges: Although IFA can provide semi-quantitative results by comparing the fluorescence intensity, it is not as precise as other methods, such as ELISA, when exact quantification of antibodies is required.

Applications

- Infectious Disease Diagnosis: IFA is widely used to detect antibodies against pathogens such as:

- Viruses: Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and others.

- Bacteria: Leptospira, Rickettsia, Chlamydia, and others.

- Parasites: Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium (malaria), and others.

- Autoimmune Disease Diagnosis: IFA is also used to detect autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases such as:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Graves’ disease

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- Research: In research, IFA is employed to study protein localization within cells, tissues, or whole organisms, especially in cases where the antigen of interest can be easily detected with a specific antibody.