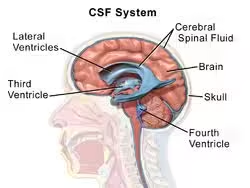

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a crucial medical diagnostic tool, especially for neurological conditions. The analysis of CSF can provide valuable insights into the functioning of the brain, spinal cord, and surrounding structures. Here’s an overview of the key aspects involved in the CSF examination:

Indications for Lumbar Puncture

Lumbar puncture is indicated for various diagnostic and therapeutic reasons, including:

- Diagnosis of infections: Meningitis (bacterial, viral, fungal, or tuberculous).

- Diagnosis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases: Multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- Diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage: CSF analysis can detect blood if a brain CT scan is inconclusive.

- Diagnosis of cancers: To check for cancerous cells in the CSF, particularly in patients with known or suspected metastases to the central nervous system (e.g., leptomeningeal carcinomatosis).

- Measurement of intracranial pressure (ICP): Conditions like idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

- Therapeutic purposes: Deliver medications (e.g., chemotherapy) directly into the CSF or reduce CSF pressure (therapeutic lumbar puncture for idiopathic intracranial hypertension).

Contraindications

Lumbar puncture is generally a safe procedure but has relative contraindications:

- Raised intracranial pressure with mass effect: This includes brain abscess, tumour, or large stroke, as lumbar puncture may result in brain herniation.

- Local skin infections at the puncture site: Risk of introducing infection into the spinal canal.

- Bleeding disorders: Increased risk of bleeding and spinal hematoma (e.g., patients on anticoagulants).

- Spinal deformities: This may make the procedure technically difficult.

Procedure

A. Preparation

- Informed Consent: The risks, benefits, and procedures are explained to the patient. Consent must be obtained before proceeding.

- Positioning:

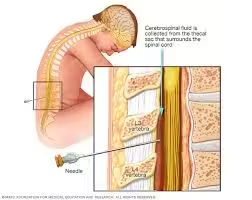

- Lateral decubitus position (most common): The patient lies on their side with knees drawn up to the chest (fetal position). The head is bent forward to increase the space between the lumbar vertebrae.

- Sitting position: This can be used, especially if the lateral decubitus position is difficult or if a higher level of precision is needed.

- Sterilization: The lumbar region is cleaned with an antiseptic solution, and a sterile drape is placed to maintain a sterile field.

B. Locating the Insertion Site

- The needle is usually inserted at the L3-L4 or L4-L5 interspace (below the level of the spinal cord termination, usually at L1-L2 in adults) to avoid injury to the spinal cord.

- A landmark found on this site is the iliac crest. The intersection of an imaginary line drawn between the iliac crests is usually at the L4 vertebra.

C. Anaesthesia

- Local anaesthesia (typically lidocaine) is injected into the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and deeper tissues to numb the area.

D. Insertion of Spinal Needle

- A spinal needle (typically 22- or 25-gauge) with a stylet is carefully inserted into the space between the vertebrae. The needle is advanced slowly until it punctures the dura mater and enters the subarachnoid space.

- The entry into the subarachnoid space is usually confirmed by a slight “pop” sensation, which is felt when the dura is punctured.

- The stylet is removed, and clear CSF should begin to drip from the needle.

E. Measurement of Opening Pressure

- If indicated, the opening pressure of the CSF is measured using a manometer attached to the needle.

- Normal CSF pressure ranges from 6 to 20 cm H₂O in a resting lateral decubitus position.

- Elevated CSF pressure can indicate conditions like meningitis, intracranial haemorrhage, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

F. Collection of CSF

- CSF is collected in sterile tubes (usually four tubes), each with a specific purpose:

- Tube 1: Chemistry (glucose, protein, lactate).

- Tube 2: Microbiology (culture, Gram stain, PCR).

- Tube 3: Cell count and differential (WBCs, RBCs).

- Tube 4: Special tests or repeat cell count (to rule out traumatic tap if the first tube contains RBCs).

G. Removal of the Needle

- Once the required amount of CSF is collected, the needle is carefully withdrawn, and the puncture site is covered with a sterile dressing.

Post-Procedure Care

- Monitor the Patient: The patient is usually observed for 1–2 hours after the procedure, particularly for any signs of complications like headache, bleeding, or neurological changes.

- Post-Lumbar Puncture Headache: A common side effect caused by a leak of CSF through the puncture site. It can typically be managed with bed rest, hydration, caffeine, and analgesics. In severe cases, a blood patch may be needed.

Potential Complications

- Post-Lumbar Puncture Headache: Occurs in about 10-30% of patients.

- Back Pain: Temporary pain at the site of the needle insertion.

- Bleeding: Rare but may occur, particularly in patients with bleeding disorders.

- Infection: Though rare, introducing infection into the spinal canal (meningitis) is a serious concern.

- Brain Herniation: If a patient has elevated intracranial pressure due to a mass lesion, herniation of the brainstem through the foramen magnum can occur.

Interpretation of Findings

- Colour: Normal CSF is clear and colourless.

- CSF Pressure: Elevated in meningitis, haemorrhage, and tumours.

- Glucose and Protein: Abnormal levels indicate infection, inflammation, or malignancy.

- Cell Count: Elevated white blood cells suggest infection or inflammation. Red blood cells may indicate haemorrhage or traumatic tap.

Physical examination

The physical examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) provides initial, valuable insights before performing more detailed biochemical and microbiological analyses. Here’s an in-depth look at the components of CSF physical examination:

Colour and Clarity

- Normal CSF: Clear and colourless, resembling water.

- Abnormal Colors:

- Turbid or cloudy: Indicates an elevated number of cells (pleocytosis), commonly seen in infections such as bacterial meningitis or in cases of a high protein content.

- Xanthochromia (yellowish discolouration): Results from the breakdown of blood in the CSF.

- Pink/red (bloody): Suggests the presence of red blood cells. This can be due to a traumatic tap or a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

- Oily appearance: when fatty substances are present.

Turbidity or Cloudiness

- Normal CSF is crystal clear.

- Turbid CSF suggests the presence of white blood cells, red blood cells, bacteria, or fungi.

- Infections: Bacterial meningitis commonly causes a turbid appearance due to many white blood cells. Tuberculous or fungal meningitis may also cause turbidity, but often to a lesser degree.

- Increased Protein: Conditions like Guillain-Barré syndrome or tumours may cause CSF to appear turbid due to the accumulation of high levels of proteins.

- Lipids: Sometimes seen in cases of increased lipids in the blood or after fat embolism.

Viscosity

- Normal CSF is slightly more viscous than water but flows easily from the needle during a lumbar puncture.

- Increased viscosity is rare but can occur in conditions like metastatic mucinous tumours or rarely in hypoproteinaemia states.

Presence of Coagulum or Clot

- Normal CSF does not clot.

- Abnormal coagulation in the CSF may occur when there is an increased amount of fibrinogen or protein, which can be seen in:

- Tuberculous meningitis: CSF may form a fibrin web or clot when allowed to sit in a test tube. This is highly suggestive of tuberculous or fungal meningitis.

- Traumatic tap: Clotting may occur due to blood contamination from the procedure.

Opening Pressure

- Normal CSF pressure ranges from 6 to 20 cm H₂O (measured with the patient in a lateral decubitus position).

- Increased opening pressure May suggest conditions such as:

- Meningitis (particularly bacterial).

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

- Cerebral oedema.

- Tumors or space-occupying lesions.

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

- Decreased opening pressure May occur in conditions such as:

- CSF leak (post-surgery, trauma, or spontaneous).

- Dehydration.

- CNS hypotension.

- Increased opening pressure May suggest conditions such as:

Chemical Analysis of CSF

Glucose

- Normal Range: Typically, CSF glucose is about 60-80% of the patient’s blood glucose level (approximately 45-80 mg/dL, depending on blood glucose concentration).

- Abnormal Findings:

- Decreased CSF Glucose:

- Bacterial Meningitis: One of the hallmark features of bacterial infections is low CSF glucose levels, typically less than 40 mg/dL (hypoglycorrhachia).

- Fungal and Tuberculous Meningitis: Also associated with low CSF glucose levels, although the reduction may be less dramatic than in bacterial meningitis.

- Carcinomatous Meningitis: Cancer cells in the CSF can cause a reduction in glucose levels.

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Blood in the CSF may also reduce glucose levels.

- Normal or Slightly Reduced Glucose:

- Viral Meningitis: CSF glucose levels are typically normal or slightly decreased in viral infections since viruses do not consume glucose like bacteria do.

- Decreased CSF Glucose:

- Significance: Hypoglycorrhachia is a critical indicator of bacterial or fungal infections, making CSF glucose one of the most important initial markers in diagnosing CNS infections.

Protein

- Normal Range: 15-45 mg/dL for adults (higher in infants and the elderly).

- Abnormal Findings:

- Increased Protein (Hyperproteinorachia):

- Bacterial Meningitis: Markedly elevated protein levels (>100 mg/dL) are often seen due to the inflammatory response and increased blood-brain barrier permeability.

- Viral Meningitis: Protein levels are typically elevated but to a lesser degree than in bacterial meningitis (50-100 mg/dL).

- Fungal and Tuberculous Meningitis: Moderate to high protein levels are common.

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Can cause very high CSF protein levels (up to 1000 mg/dL) without an increase in white blood cells.

- Subarachnoid Haemorrhage: Elevated protein due to the presence of blood and breakdown of cells in the CSF.

- Tumors, Abscesses, and Inflammatory Disorders: Tumors, CNS abscesses, or diseases like multiple sclerosis can also elevate protein levels.

- Decreased Protein:

- It is not commonly seen but can occur in situations like a CSF leak due to the dilution of CSF.

- Increased Protein (Hyperproteinorachia):

- Significance: Protein elevation provides clues about the presence of infection, inflammation, or other disruptions in the blood-brain barrier, and very high levels can indicate severe pathology.

Lactate

- Normal Range: 1.2-2.1 mmol/L.

- Abnormal Findings:

- Increased Lactate:

- Bacterial Meningitis: High levels of lactate (>3.5 mmol/L) indicate bacterial infection due to the anaerobic metabolism of the invading organisms and impaired oxygenation in the inflamed tissues.

- Fungal and Tuberculous Meningitis: Moderate increases in lactate can be seen.

- Stroke: Elevated lactate may indicate areas of ischemia or reduced oxygen supply to the brain.

- Normal or Slightly Increased Lactate:

- Viral Meningitis: Lactate levels are usually normal or only slightly elevated in viral infections.

- Increased Lactate:

- Significance: Lactate is particularly useful in distinguishing between bacterial and viral meningitis. High levels strongly suggest a bacterial cause, which requires more aggressive treatment.

Chloride

- Normal Range: 110-130 mEq/L.

- Abnormal Findings:

- Decreased Chloride:

- Tuberculous Meningitis: Chloride levels are often reduced in TB meningitis.

- Other Infections: Prolonged bacterial or fungal infections may also lower CSF chloride, though it is not a commonly measured parameter today.

- Decreased Chloride:

- Significance: Chloride levels are rarely used as a primary diagnostic tool in modern practice, as more specific and sensitive markers (such as glucose and lactate) are preferred.

Cellular Examination (Cytology)

- Cell Count: Normal CSF contains very few cells (0–5 white blood cells/µL). Increased white blood cell count (pleocytosis) indicates infection, inflammation, or malignancy.

- Neutrophils: High in bacterial meningitis.

- Lymphocytes: Predominant in viral, fungal, or tuberculous meningitis and autoimmune conditions.

- Red Blood Cells (RBCs): RBCs can indicate bleeding (e.g., subarachnoid haemorrhage) or trauma during a lumbar puncture.

Microbiological Examination

- Gram Stain and Culture: Used to identify bacterial organisms in suspected meningitis cases.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Helps detect viral pathogens like herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and enteroviruses.

- India Ink Stain: Used for detecting Cryptococcus in fungal meningitis.

- Acid-Fast Staining: Important for diagnosing tuberculous meningitis.

Serological and Immunological Tests

- Antibody Detection: Useful for diagnosing neurosyphilis or autoimmune diseases.

- Antigen Detection: Helpful in diagnosing specific pathogens (e.g., Cryptococcal antigen in fungal meningitis).

Other Special Tests

- Beta-2 transferrin: A specific marker for CSF, useful in diagnosing CSF leaks.

- Tau Protein and Amyloid Beta: Used to diagnose neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Clinical Significance:

- Infections: Bacterial, viral, fungal, and tuberculous meningitis, encephalitis.

- Haemorrhage: Subarachnoid haemorrhage (xanthochromia, RBCs in the fluid).

- Autoimmune Diseases: Multiple sclerosis (oligoclonal bands, myelin basic protein).

- Malignancy: Detection of cancer cells, leptomeningeal disease.

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer’s disease (biomarker analysis).