AIM: Determination of Differential Leukocyte Count (DLC)

Principle

- The DLC is based on the microscopic examination of a blood smear stained with specific dyes (typically Wright’s stain or Giemsa stain).

- These stains highlight the morphological differences between the various types of leukocytes, allowing their identification.

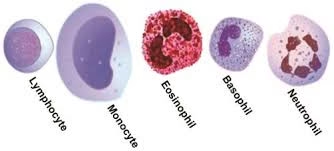

- Each WBC type has distinct features in its nucleus (size, shape, and number of lobes) and cytoplasm (color, texture, and granules), making it possible to classify them into the five major categories:

- The principle of the DLC is that the number of each type of leukocyte is counted and expressed as a percentage of the total white blood cell count.

- A minimum of 100–200 cells are typically counted to ensure an accurate result.

- The DLC result provides insight into the immune system’s state, which is important for diagnosing various diseases and conditions.

Requirements

-

Staining Solutions: Wright’s and Giemsa stains.

-

Glass Slides

-

Pipette

-

Counter or automated system

Procedure

Preparation of Blood Smear

-

A small drop of blood is placed on one end of a clean glass slide.

-

Using another clean slide at a 30–45 degree angle, the blood drop is spread across the slide by moving the angled slide across the blood drop, creating a thin, even layer of blood on the slide.

-

The slide should be spread quickly and evenly to avoid clumping of the cells or making the smear too thick, which could interfere with examination.

Staining the Blood Smear

-

Once the blood smear is prepared and allowed to air dry, it is ready for staining.

-

The smear is placed in Wright’s stain or Giemsa stain for a few minutes. These stains allow the different types of leukocytes to be clearly differentiated by coloring the cytoplasm and nuclei.

-

After staining, the slide is washed gently with water to remove excess stain.

-

The smear is allowed to air dry completely before examination.

Examination Under the Microscope

-

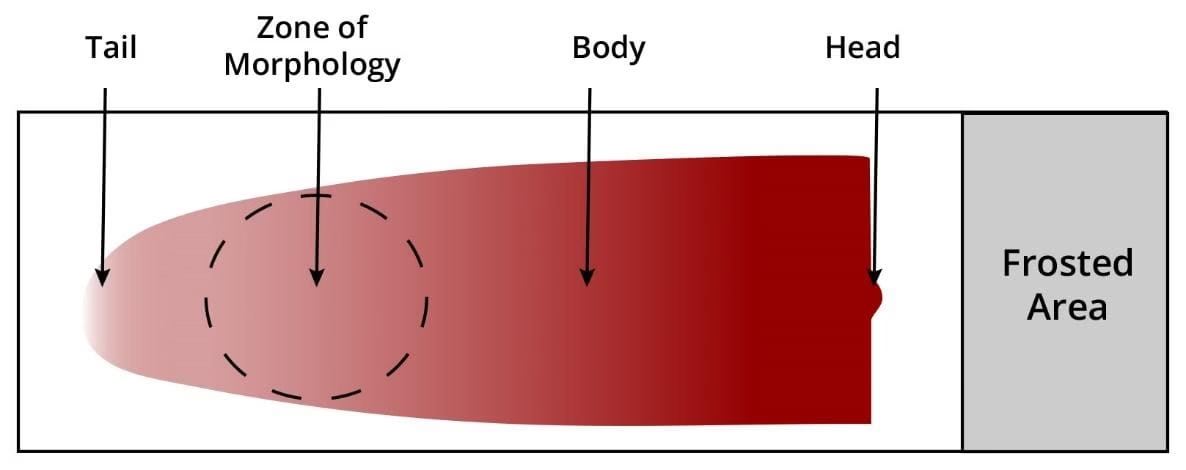

The stained smear is placed on the microscope stage, and the initial scanning is done at low magnification (10x or 40x) to find an area of the smear that has an optimal spread of cells (neither too thick nor too thin).

-

The slide is then examined under oil immersion (100x), where the WBCs can be clearly observed, and their morphological characteristics (e.g., size, shape, staining pattern) can be assessed.

Identifying the White Blood Cells

-

In the oil immersion lens view, the cytoplasm and nucleus of each WBC are carefully observed and classified based on their distinct characteristics. The classification is as follows:

-

Neutrophils: These are the most abundant WBCs and have a multi-lobed nucleus (typically 2–5 lobes) and pale cytoplasm with fine granules. They are primarily involved in the defense against bacterial infections.

-

Lymphocytes: These cells have a large, round nucleus that occupies most of the cell, with a thin rim of cytoplasm. Lymphocytes are essential in adaptive immunity, including responses to viral infections.

-

Monocytes: The largest of the WBCs, monocytes have a kidney-shaped or horseshoe-shaped nucleus and abundant cytoplasm. They mature into macrophages and play a role in phagocytosis.

-

Eosinophils: These cells have a bi-lobed nucleus and distinct red or orange granules in their cytoplasm. They are involved in allergic reactions and combating parasitic infections.

-

Basophils: These are the least common WBCs and contain large blue or purple granules in the cytoplasm. They are involved in allergic responses and inflammation.

-

Counting and Reporting

-

A minimum of 100–200 white blood cells are counted to obtain an accurate count of the different types of leukocytes.

-

The number of each type of WBC is recorded, and the percentage of each type is calculated based on the total WBC count.

-

In some cases, absolute counts of each type of WBC are calculated by multiplying the percentage of each type by the total WBC count obtained from a hemocytometer or automated counter.

Reporting

-

The result of the DLC is reported in percentages (e.g., Neutrophils: 60%, Lymphocytes: 30%, etc.) and, in some cases, as absolute values.

-

Any deviations from normal ranges are noted, as they can indicate the presence of an underlying medical condition.

Clinical Significance

The DLC provides invaluable diagnostic information regarding a patient’s immune system and can assist in identifying a range of conditions, including infections, inflammatory diseases, allergic reactions, and hematological disorders. Below is an explanation of the clinical significance of each type of WBC:

Neutrophils:

-

Neutrophilia (Increased neutrophils): Neutrophil count may increase in response to bacterial infections, inflammatory conditions, stress, or tissue damage (e.g., burns). A dramatic increase in neutrophils can be seen in conditions like acute bacterial infections, sepsis, or myelogenous leukemia.

-

Neutropenia (Decreased neutrophils): A low neutrophil count may occur due to viral infections (e.g., influenza, HIV), bone marrow disorders, chemotherapy, or autoimmune diseases.

Lymphocytes:

-

Lymphocytosis (Increased lymphocytes): An elevated lymphocyte count is often seen in viral infections (e.g., mononucleosis, hepatitis, or measles), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and whooping cough. It can also be seen in autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis).

-

Lymphopenia (Decreased lymphocytes): A reduced lymphocyte count can indicate immunodeficiency, corticosteroid use, HIV infection, or systemic corticosteroid treatment.

Monocytes:

-

Monocytosis (Increased monocytes): An increase in monocytes is often seen in chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, brucellosis), inflammatory disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), and leukemia (e.g., chronic myelomonocytic leukemia).

-

Monocytopenia (Decreased monocytes): A decrease in monocytes is less common, but it can be seen in bone marrow disorders, corticosteroid use, and certain viral infections.

Eosinophils:

-

Eosinophilia (Increased eosinophils): An elevated eosinophil count is most commonly seen in allergic reactions (e.g., asthma, hay fever), parasitic infections (e.g., hookworm, roundworm), and some autoimmune conditions (e.g., eosinophilic granulomatosis).

-

Eosinopenia (Decreased eosinophils): A low eosinophil count is often associated with stress, acute infection, or corticosteroid therapy.

Basophils:

-

Basophilia (Increased basophils): Basophil levels may increase in conditions such as chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), hypersensitivity reactions, and chronic inflammation.

-

Basopenia (Decreased basophils): A decrease in basophils is generally not of major concern and may occur due to acute infection or stress.