Diphyllobothrium latum, commonly known as the broad fish tapeworm, is one of the largest tapeworm species infecting humans. It primarily resides in the small intestine of humans and other carnivorous mammals.

Habitat

- Definitive Host: The adult tapeworm resides in the small intestine of the definitive host, which is usually a human or carnivorous mammal (e.g., dogs, cats, bears).

- Intermediate Hosts: The intermediate hosts are typically freshwater fish, such as pike, perch, and salmon, which ingest the larval stages of the parasite. Crustaceans like copepods can also serve as intermediate hosts, particularly during the larval stages.

Epidemiology

- Geographic Distribution:

- D. latum is found worldwide, with high prevalence in areas where raw or undercooked freshwater fish is commonly consumed.

- It is most common in northern Europe, Russia, Asia, and North America, where traditional diets involve the consumption of raw or inadequately cooked fish.

- In some parts of the world, the parasite is also common in South America, particularly in regions where freshwater fish are part of the local diet.

- Transmission:

- Humans become infected by eating raw, undercooked, or pickled freshwater fish containing infected plerocercoid larvae (the infective stage).

- Fish-eating mammals (definitive hosts) release proglottids containing eggs into the water via feces, where they hatch and develop into larvae.

Morphology

- Adult Tapeworm:

- Size: The adult tapeworm is long (up to 10 meters), with a flattened, ribbon-like body.

- Scolex: The scolex (head) has two sucking grooves (bothria) that help it attach to the host’s intestinal wall. This is a distinguishing feature of D. latum compared to other tapeworms.

- Proglottids: The proglottids are large, rectangular, and broader than long. The proglottids contain numerous eggs and are released into the environment via the host’s feces.

- Eggs:

- The eggs are oval, with a lid-like operculum at one end. They measure about 60–75 µm in length and contain a coracidium, a ciliated embryo released into water and infects intermediate hosts.

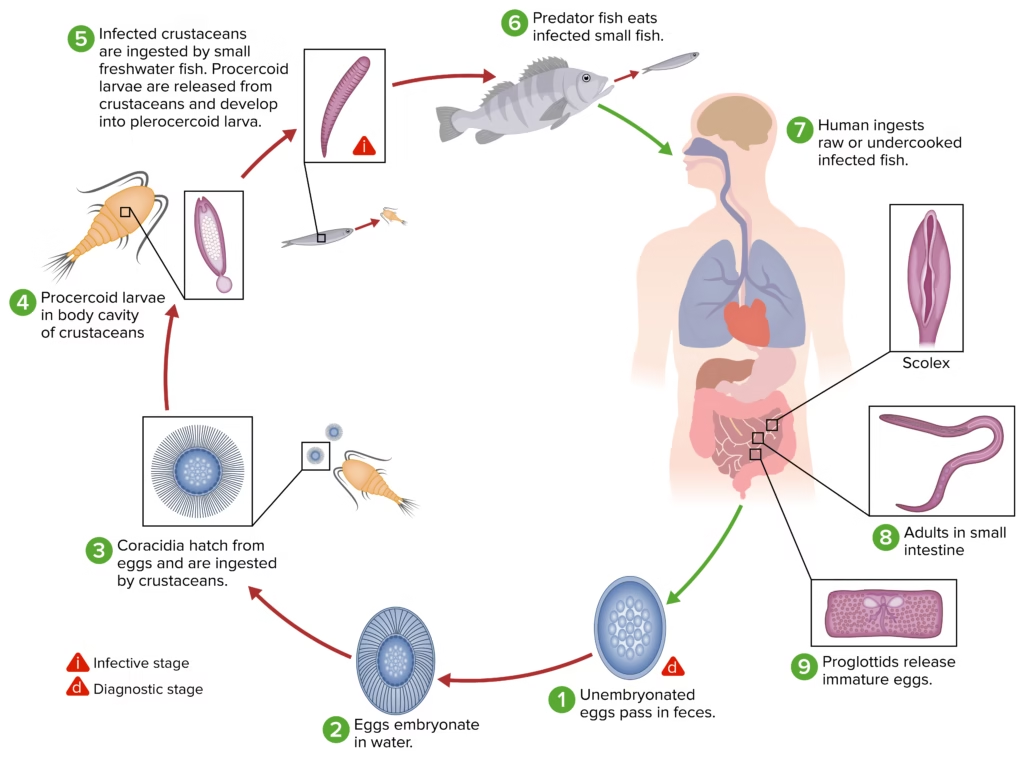

Life Cycle

The life cycle of D. latum involves multiple hosts and stages:

- Eggs in Water:

- The eggs are released from the definitive host (e.g., humans, carnivorous mammals) through feces into the environment, where they hatch in freshwater.

- Coracidium Stage:

- The eggs hatch in the water to release a coracidium, a ciliated larval form.

- This coracidium is ingested by copepods (the first intermediate host) in freshwater.

- Procercoid Stage:

- Inside the copepod, the coracidium develops into the procercoid larva.

- Infection of Fish:

- The infected copepod is eaten by a freshwater fish (second intermediate host), where the procercoid larvae develop into the plerocercoid larval stage in the fish muscles and tissues.

- Infection of Definitive Host:

- A human or other fish-eating carnivores consume the infected fish, ingesting the plerocercoid larvae.

- In the host’s small intestine, the larvae attach to the intestinal wall, mature into adults, and release eggs into the environment through feces, completing the cycle.

Pathogenesis

- Pathophysiology:

- The adult tapeworm lives in the small intestine, which can grow up to several meters long. The scolex (head) of the worm attaches to the intestinal wall, where it absorbs nutrients from the host.

- The parasite does not typically invade host tissues but may cause a range of symptoms due to its size and presence in the intestines.

- Symptoms:

- In many cases, D. latum infections are asymptomatic or cause mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Symptoms may include:

- Abdominal discomfort

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- B12 deficiency (in some cases) can lead to anemia due to the worm’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 from the host.

- Rarely, the infection can cause intestinal obstruction, especially in heavy infestations.

- Complications:

- Vitamin B12 deficiency may lead to megaloblastic anemia in chronic infections.

- Intestinal obstruction may occur in cases of large worm burdens.

- Perforation of the intestine is a rare but severe complication.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Microscopic Examination of Stool:

- Fecal samples are examined under a microscope to detect the characteristic eggs of D. latum.

- The eggs are oval-shaped with an operculated lid and measure 60–75 µm in length.

- Fecal flotation methods using zinc sulfate or other flotation solutions help to concentrate eggs for easier detection.

- Serological Tests:

- ELISA and Western blot assays may detect specific antibodies against D. latum, though these tests are not widely used for routine diagnosis.

- Endoscopy and Imaging:

- In cases of severe infections, endoscopic examination may reveal the presence of adult tapeworms in the small intestine.

- Radiographic imaging may show the characteristic large size of the tapeworm in the intestines in cases of heavy infection.

Summary Table: Diphyllobothrium latum

| Aspect | Description |

| Habitat | The small intestine of humans (definitive host) and carnivorous mammals. Fish and copepods serve as intermediate hosts. |

| Epidemiology | Found in areas with raw or undercooked freshwater fish consumption. Common in northern Europe, Russia, Asia, and North America. |

| Morphology | Adult: Long (up to 10 m), flattened, with a scolex and two sucking grooves (bothria). Eggs: Oval, operculated, with a coracidium. |

| Life Cycle | Eggs hatch into coracidia in water, ingested by copepods and fish. Humans ingest infected fish, where the larvae mature into adults in the small intestine. |

| Pathogenesis | Mostly asymptomatic, but can cause abdominal discomfort, nausea, and B12 deficiency leading to anemia. Heavy infections can lead to intestinal obstruction. |

| Laboratory Diagnosis | Microscopic stool examination for eggs, fecal flotation techniques, PCR for detection of larvae, serology, and endoscopic examination in severe cases. |

Prevention and Control

- Food Safety:

- Avoid consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater fish. Ensure proper cooking or freezing of fish to kill D. latum larvae.

- Sanitation:

- Proper sanitation and hygiene can reduce the risk of contamination from the feces of infected animals.

- Health Education:

- Educating populations in endemic areas about the risks of consuming undercooked fish is essential for prevention.