Hymenolepis nana, commonly known as the dwarf tapeworm, is a parasitic tapeworm that primarily infects humans and is one of the most common tapeworms infecting humans worldwide, especially in areas with poor sanitation.

Habitat

- Definitive Host: Hymenolepis nana inhabits the small intestine of humans and other rodents, living as an adult tapeworm.

- Intermediate Hosts: The larval stage can also infect arthropods, such as beetles and cockroaches, which are accidental intermediate hosts. However, humans can also serve as intermediate hosts in certain cases.

Epidemiology

- Geographic Distribution:

- H. nana is found worldwide but is particularly prevalent in developing countries with poor sanitation and hygiene.

- The disease is common in overcrowded areas where contaminated food or water is consumed.

- It is also frequently observed in children, who are more likely to ingest contaminated food or water.

- Transmission:

- Direct transmission: Humans can become infected by ingesting H. nana eggs directly from contaminated food, water, or surfaces or through self-infection (auto-infection), where the eggs hatch within the intestine and release larvae that reinfect the same host.

- Indirect transmission: The eggs can also be ingested by intermediate hosts (e.g., beetles and cockroaches) that consume contaminated food or feces, and when humans consume these infected hosts, they may acquire the infection.

Morphology

- Adult Tapeworm:

- The adult H. nana is small, measuring about 15–40 mm long and 1–2 mm wide.

- It has a scolex (head) equipped with four suckers and a rostellum (with hooks), which allows it to attach to the wall of the small intestine.

- The tapeworm’s body consists of a short chain of proglottids (segments) containing eggs.

- The gravid proglottids release the eggs into the environment via the host’s feces.

- Eggs:

- The H. nana eggs are spherical and measure 30–47 µm in diameter.

- They have a thick, bile-stained outer shell and contain a hexacanth embryo with six hooks (hence, the name “Hymenolepis”), which can infect the host when ingested.

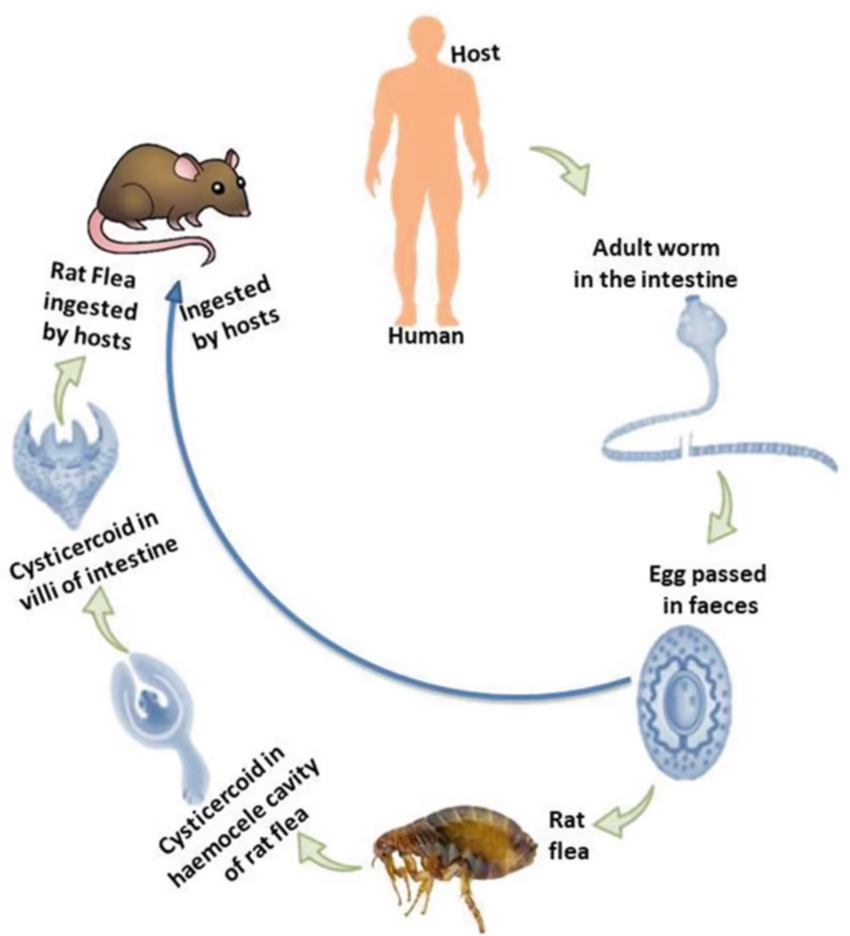

Life Cycle

- Eggs in the Environment:

- The gravid proglottids of the adult tapeworm release eggs into the environment through the feces of the definitive host.

- The eggs can infect intermediate hosts (like beetles and cockroaches) and humans.

- Infection of Intermediate Hosts:

- The eggs are ingested by arthropods that become intermediate hosts.

- Inside the arthropod, the egg hatches into a larval form called a cysticercoid, which develops within the arthropod.

- Infection of Definitive Host (Human):

- Humans can ingest eggs directly (contaminated food, water, or surfaces) or consume infected intermediate hosts (e.g., beetles).

- Once ingested, the eggs hatch in the small intestine and release oncospheres that penetrate the intestinal wall.

- The oncospheres develop into cysticercoids, which mature into adult tapeworms that attach to the intestinal wall and produce new proglottids.

- Self-Infection:

- The larvae can also cause auto-infection, where oncospheres hatch and develop into adult tapeworms in the same host, leading to continued cycles of infection.

- Release of Eggs:

- The adult tapeworms produce gravid proglottids containing eggs, which are released into the host’s feces, completing the cycle.

Pathogenesis

- Infection with Hymenolepis nana is typically asymptomatic in many cases, but it can lead to mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Pathological Effects:

- Intestinal Inflammation: The adult tapeworm in the small intestine can cause mild inflammation and irritation of the intestinal wall.

- Abdominal Symptoms: Infected individuals may experience abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, or weight loss.

- Auto-infection: In cases of auto-infection, the burden of tapeworms may increase, leading to more severe symptoms such as anemia, intestinal obstruction, or even perforation in extreme cases.

- Immune Response:

- The immune system may mount a response to the tapeworms, but since H. nana is a small tapeworm, it usually does not cause significant immune complications or systemic involvement.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Microscopy:

- Fecal Examination: The primary diagnostic method is the presence of H. nana eggs in fecal samples. The eggs are spherical with a bile-stained outer shell and a hexacanth embryo inside.

- Flotation Techniques: Fecal samples are often processed with floatation solutions (e.g., Zinc sulfate) to concentrate and visualize the eggs.

- Molecular Diagnosis:

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) can identify H. nana DNA in stool samples, providing a more sensitive and specific test, especially in cases of low egg shedding.

- Serological Tests:

- Serologic tests are not routinely used for H. nana due to the localized nature of the infection. However, antibody detection might be used in specific cases to confirm exposure.

- Endoscopic Diagnosis:

- In rare cases, if the tapeworm is large enough, endoscopic examination of the small intestine may reveal the presence of adult tapeworms or proglottids.

Summary Table: Hymenolepis nana

| Aspect | Description |

| Habitat | The small intestine of humans (definitive host); arthropods (intermediate hosts). |

| Epidemiology | Worldwide, especially in developing countries with poor sanitation and hygiene. Transmission through ingestion of eggs or infected arthropods. |

| Morphology | Small adult tapeworm (15–40 mm), with a scolex and suckers. Gravid proglottids contain eggs. Eggs are spherical with a hexacanth embryo. |

| Life Cycle | Eggs ingested by intermediate hosts or directly by humans; larvae develop into adult tapeworms in the small intestine; auto-infection is possible. |

| Pathogenesis | Typically asymptomatic, but can cause gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea). Auto-infection may increase severity. |

| Laboratory Diagnosis | Fecal microscopy for eggs, PCR for DNA detection, serology in some cases, and endoscopic examination in rare cases. |

Prevention and Control

- Good Hygiene: Ensuring clean water access and sanitation practices can reduce transmission.

- Food Safety: Avoid consuming contaminated food or water and washing hands regularly.

- Deworming: Regular deworming of children and people in endemic areas to reduce the spread of eggs.

- Insect Control: Control of arthropod vectors (such as cockroaches and beetles) in homes can prevent intermediate host infection.