Introduction

-

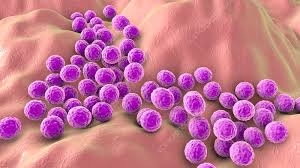

Staphylococci are Gram-positive cocci that typically appear in grape-like clusters due to division in multiple planes.

-

They are non-motile, non-spore-forming, and facultative anaerobes.

-

Staphylococci are widely present in nature and form part of the normal flora of skin, anterior nares, and mucous membranes of humans.

-

They are catalase-positive, which differentiates them from Streptococci (catalase-negative).

-

Based on coagulase production, they are divided into:

-

Coagulase-positive (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus)

-

Coagulase-negative (e.g., S. epidermidis, S. saprophyticus)

-

-

Staphylococci are highly resistant to environmental conditions, surviving drying, heat, and high salt concentrations.

-

They produce multiple virulence factors such as enzymes, toxins, and adhesion molecules, enabling colonization and invasion.

-

Clinically, they are major causes of pyogenic infections, wound infections, abscesses, and device-related infections.

-

Some strains (especially S. aureus) cause toxin-mediated diseases like food poisoning, scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome.

-

Staphylococci are significant hospital-acquired (nosocomial) pathogens, including MRSA strains with antimicrobial resistance.

General Character

- Genus: Staphylococcus

- Family: Staphylococcaceae

- Gram Staining: Staphylococci are Gram-positive, appearing purple under a microscope due to their thick peptidoglycan layer.

- Shape and Arrangement:

- Shape: They are spherical (cocci) in shape.

- Arrangement: Staphylococci are typically found in clusters resembling grapes due to division in multiple planes without separation.

- Oxygen Requirements: Staphylococci are facultative anaerobes. This means they can grow in both the presence and absence of oxygen, allowing them to inhabit diverse environments, including human skin and mucosal surfaces.

Morphology

- Cell Wall Structure:

- Composed of a thick peptidoglycan layer (approximately 30-80% of the cell wall) provides structural integrity and helps resist osmotic pressure.

- It contains teichoic acids that play roles in cell wall maintenance and regulation of cell growth.

- Capsule:

- Some species, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, possess a polysaccharide capsule that helps evade phagocytosis by immune cells.

- Surface Structures:

- Slime Layer: Contributes to biofilm formation, particularly in coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), enhancing adherence to surfaces like catheters and prosthetic devices.

- Flagella: Staphylococci are non-motile, lacking flagella and using other mechanisms for adherence and colonization.

Cultural Characteristics

- Growth Media:

- Blood Agar: Supports the growth of various staphylococcal species and allows for hemolysis observation. S. aureus shows β-hemolysis, while S. epidermidis is usually non-hemolytic.

- Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA): A selective medium for staphylococci. It contains high salt concentration (7.5% NaCl) and mannitol. S. aureus ferments mannitol, resulting in a yellow colour change, while S. epidermidis does not ferment it and remains red.

- Colony Appearance:

- Colonies of S. aureus are typically golden-yellow due to carotenoid pigments, while S. epidermidis colonies are usually white or off-white.

- Temperature and pH Range:

- The optimal growth temperature is around 37°C, but they can grow between 15°C and 45°C.

- They can tolerate a broad pH range, but neutral pH is preferred for optimal growth.

Biochemical Reactions

- Catalase Test: Staphylococci produce the enzyme catalase, which converts hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, resulting in bubbling. This distinguishes them from streptococci, which are catalase-negative.

- Coagulase Test:

- S. aureus: Positive for coagulase, causing plasma to clot.

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS), like S. epidermidis, are usually coagulase-negative.

- Mannitol Fermentation:

- S. aureus: Ferments mannitol, producing acid and causing a colour change in MSA.

- S. epidermidis: Does not ferment mannitol.

- Other Biochemical Tests:

- Oxidase Test: Negative.

- Urease Test: Variable; most strains of S. saprophyticus are urease-positive, while others are typically negative.

- DNase Test: Positive for S. aureus, indicating the ability to degrade DNA. This is a differentiating feature for identifying S. aureus.

Pathogenicity

- Virulence Factors:

- Toxins:

- Enterotoxins: Heat-stable toxins responsible for food poisoning, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin (TSST-1): A superantigen that can cause toxic shock syndrome characterized by fever, rash, and multi-organ failure.

- Alpha-toxin: A pore-forming toxin that disrupts cell membranes, causing tissue damage and necrosis.

- Enzymes:

- Coagulase: Promotes clot formation, helping to shield the bacteria from immune responses.

- Hyaluronidase: Breaks down hyaluronic acid in connective tissue, facilitating tissue invasion.

- Lipase: Allows for colonization of sebaceous glands by breaking down lipids.

- Adhesins: Surface proteins that promote binding to host tissues, critical for colonization and infection.

- Toxins:

- Clinical Infections:

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: Commonly cause boils, abscesses, impetigo, and cellulitis.

- Invasive Infections: This can lead to more severe conditions like endocarditis (infection of the heart valves), osteomyelitis (bone infection), and septic arthritis.

- Respiratory Infections: S. aureus can cause pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised individuals or those with chronic lung disease.

- Food Poisoning: Resulting from ingestion of food contaminated with enterotoxins, leading to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

- Opportunistic Pathogen:

- S. epidermidis: Often associated with infections related to medical devices (e.g., catheters, prosthetic joints) due to biofilm formation.

- S. saprophyticus: A common cause of urinary tract infections, particularly in young women.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Specimen Collection: Obtaining samples from infected sites (e.g., skin lesions, abscesses, blood, urine). The choice of specimen depends on the clinical presentation.

- Microscopic Examination:

- A Gram stain of the specimen reveals Gram-positive cocci in clusters.

- This initial finding guides further testing and identification.

- Culture Techniques:

- Inoculation: Samples are inoculated on blood agar and MSA to promote growth and identify species.

- Incubation: Cultures are typically incubated at 35-37°C for 24-48 hours.

- Colony Morphology Examination: Observing colony colour and morphology aids in preliminary identification.

- Biochemical Testing:

- Catalase Test: Distinguishes staphylococci from streptococci.

- Coagulase Test: Essential for differentiating S. aureus from CoNS.

- Mannitol Fermentation Test: Further identifies S. aureus based on mannitol fermentation.

- Additional tests may include the DNase and urease tests, depending on the suspected species.

- Molecular Methods:

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other nucleic acid amplification techniques can provide rapid and specific identification of staphylococci and detection of antibiotic resistance genes.

- These methods are especially useful in outbreaks or cases of severe infections.

Antibiotic Resistance

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): A significant public health concern due to its resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. MRSA strains are often associated with severe infections and are prevalent in both hospital and community settings.

- Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA): The emergence of strains resistant to vancomycin complicates treatment options.

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococci: Increasingly recognized for their resistance to multiple antibiotics, posing challenges in treating infections associated with implanted medical devices.

MCQs

1. Staphylococci appear microscopically as:

A. Gram-negative rods

B. Gram-positive cocci in chains

C. Gram-positive cocci in clusters

D. Gram-negative cocci

2. The word “staphyle” means:

A. Chain

B. Grape

C. Spiral

D. Rod

3. Staphylococci are:

A. Motile

B. Non-motile

C. Spore forming

D. Acid-fast

4. Staphylococci are:

A. Obligate anaerobes

B. Facultative anaerobes

C. Strict aerobes

D. Microaerophilic

5. Staphylococci are differentiated from Streptococci by:

A. Oxidase test

B. Catalase test

C. Coagulase test

D. Urease test

6. The most pathogenic species of Staphylococcus is:

A. S. epidermidis

B. S. aureus

C. S. saprophyticus

D. S. hominis

7. Staphylococcus aureus colonies typically appear:

A. White

B. Golden yellow

C. Red

D. Green

8. The enzyme that differentiates S. aureus from other staphylococci is:

A. Catalase

B. Oxidase

C. Coagulase

D. Urease

9. Majority of Staphylococci on skin are:

A. Coagulase-positive

B. Coagulase-negative

C. Acid-fast

D. Motile

10. Catalase-positive organisms include:

A. Streptococcus

B. Staphylococcus

C. Enterococcus

D. Pneumococcus

11. Hemolysis pattern of S. aureus on blood agar is:

A. Alpha

B. Beta

C. Gamma

D. None

12. S. aureus ferments mannitol to produce:

A. Red colonies

B. Yellow colonies

C. Black colonies

D. White colonies

13. Mannitol Salt Agar selects for Staphylococci due to:

A. High sugar

B. High NaCl concentration

C. Low pH

D. Antibiotics

14. S. epidermidis is best known for:

A. Food poisoning

B. Toxic shock syndrome

C. Biofilm formation

D. Skin peeling toxin

15. S. saprophyticus commonly causes:

A. Pneumonia

B. UTI in young women

C. Meningitis

D. Osteomyelitis

16. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci include:

A. S. aureus

B. S. epidermidis

C. S. pyogenes

D. E. coli

17. The major virulence factor of S. aureus that binds IgG is:

A. Exotoxin A

B. Protein A

C. Hemolysin

D. Coagulase

18. Staphylococcal enterotoxin causes:

A. Diarrhea after 6–12 hours

B. Rapid food poisoning within hours

C. Jaundice

D. Meningitis

19. Toxic Shock Syndrome is caused by:

A. TSST-1

B. Coagulase

C. Beta toxin

D. Alpha hemolysin

20. MRSA carries which gene?

A. blaZ

B. mecA

C. vanA

D. tetM

21. mecA gene encodes:

A. Beta-lactamase

B. Altered PBP2a

C. Protein A

D. Coagulase

22. First-line drug for serious MRSA infection is:

A. Penicillin

B. Vancomycin

C. Gentamicin

D. Tetracycline

23. Common colonization site for S. aureus is:

A. Rectum

B. Nasal cavity

C. Mouth

D. Stomach

24. Staphylococci divide along:

A. One plane

B. Multiple planes

C. Spiral axis

D. Horizontal axis

25. S. aureus possesses:

A. Capsule

B. Flagella

C. Spores

D. Fimbriae

26. Staphylococcal alpha toxin causes:

A. Protein synthesis inhibition

B. Membrane pore formation

C. DNA damage

D. Neurotoxicity

27. Enterotoxins of S. aureus are:

A. Heat-labile

B. Heat-stable

C. Inactivated by cooking

D. Antibiotic sensitive

28. A common hospital-acquired infection caused by S. aureus is:

A. Malaria

B. Surgical wound infection

C. Liver abscess

D. Typhoid

29. S. epidermidis infections commonly involve:

A. Catheters and implants

B. Lungs

C. GI tract

D. Kidneys

30. Coagulase test positive means:

A. No clot formation

B. Clot formation

C. Color change only

D. Rapid hemolysis

31. Staphylococci tolerate:

A. 1% NaCl

B. 7.5% NaCl

C. No salt

D. Only low-salt medium

32. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is due to:

A. TSST-1

B. Exfoliative toxin

C. Enterotoxin

D. Hemolysin

33. Food poisoning by S. aureus is due to:

A. Infection

B. Preformed toxin

C. Endotoxin

D. Coagulase

34. Staphylococci are part of normal flora of:

A. Skin

B. Blood

C. CSF

D. Bone marrow

35. Novobiocin resistance helps differentiate:

A. S. aureus

B. S. saprophyticus

C. S. epidermidis

D. S. hominis

36. Biofilm formation is a key virulence factor of:

A. S. aureus

B. S. epidermidis

C. S. saprophyticus

D. S. lugdunensis

37. On Gram stain, Staphylococci appear:

A. Pink rods

B. Purple cocci

C. Pink cocci

D. Purple rods

38. S. aureus is commonly associated with:

A. Impetigo

B. Pneumonia

C. Osteomyelitis

D. All of the above

39. Beta-lactamase in S. aureus causes resistance to:

A. Methicillin

B. Penicillin

C. Vancomycin

D. Linezolid

40. The most common coagulase-negative Staphylococcus causing device infections is:

A. S. aureus

B. S. epidermidis

C. S. saprophyticus

D. S. hominis

41. Staphylococci grow best at:

A. 20°C

B. 25°C

C. 35–37°C

D. 50°C

42. Staphylococcal toxic shock involves:

A. Superantigen activity

B. Endotoxin action

C. Viral mimicry

D. Hemolysis only

43. Staphylococci are:

A. Acid-fast

B. Non–acid-fast

C. Weakly acid-fast

D. Obligate acid-fast

44. Cell wall of Staphylococci contains:

A. Mycolic acid

B. Teichoic acid

C. Lipopolysaccharide

D. Capsule only

45. S. aureus beta hemolysis results from:

A. Protein A

B. Hemolysins

C. Coagulase

D. Capsule

46. The enzyme catalase breaks down:

A. H₂O₂ → H₂O + O₂

B. H₂O → H⁺ + OH⁻

C. CO₂ → CO + O₂

D. Lipids → fatty acids

47. Staphylococci are best cultured on:

A. MacConkey agar

B. Mannitol salt agar

C. SS agar

D. Thiosulfate agar

48. The structure allowing S. epidermidis to stick to surfaces is:

A. Flagella

B. Biofilm

C. Pili

D. Fimbriae

49. Exfoliative toxin causes:

A. Peeling of skin

B. Food poisoning

C. Fever only

D. Kidney injury

50. S. aureus pneumonia is often seen following:

A. Viral influenza

B. COVID-19 only

C. Asthma

D. Common cold

✅ Answer Key

1-C

2-B

3-B

4-B

5-B

6-B

7-B

8-C

9-B

10-B

11-B

12-B

13-B

14-C

15-B

16-B

17-B

18-B

19-A

20-B

21-B

22-B

23-B

24-B

25-A

26-B

27-B

28-B

29-A

30-B

31-B

32-B

33-B

34-A

35-B

36-B

37-B

38-D

39-B

40-B

41-C

42-A

43-B

44-B

45-B

46-A

47-B

48-B

49-A

50-A