Introduction

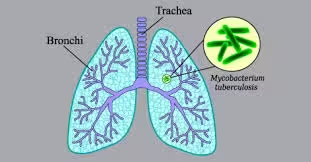

- Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant global health issue, affecting millions of individuals each year.

- The causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is an aerobic bacterium that primarily targets the lungs but can also affect other organs.

- Effective laboratory diagnosis is essential for timely treatment and control of TB transmission.

Clinical Presentation

Common Symptoms

- Pulmonary TB:

- Chronic Cough: Often productive and lasting longer than three weeks.

- Hemoptysis: Coughing up blood or blood-stained sputum.

- Systemic Symptoms: Fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue.

- Extrapulmonary TB:

Symptoms depend on the site of infection:

-

- Lymphatic TB: Swelling of lymph nodes.

- Pleural TB: Chest pain and difficulty breathing.

- Bone TB: Localized pain and swelling.

- Renal TB: Flank pain and hematuria.

Sample Collection

- Sputum Samples

- Importance: Sputum is the primary specimen for diagnosing pulmonary TB.

- Collection Process:

- To minimize contamination, patients should be instructed to produce sputum in the morning, ideally after mouth rinsing.

- Collect three samples on consecutive days for the best yield.

- Other Specimens

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL): This is often used when sputum samples are insufficient or difficult to obtain. During bronchoscopy, fluid is introduced into the lungs and then collected.

- Pleural Fluid: For patients with suspected pleural TB, thoracentesis can be performed to obtain pleural fluid.

- Tissue Biopsies: In cases of extrapulmonary TB, biopsies of affected tissues (e.g., lymph nodes, bones) can provide material for culture and histopathological examination.

- Urine Samples: Useful in cases of renal TB, where urine may be tested for M. tuberculosis.

Laboratory Techniques

Microscopy

A. Acid-Fast Bacilli (AFB) Staining

B. Ziehl-Neelsen Stain:

-

- Sputum smears are stained and examined under a light microscope. AFB will appear bright red against a blue background.

- This method can detect M. tuberculosis but has limitations in sensitivity; not all TB cases will show AFB.

Fluorescent Microscopy

- Auramine-O Staining:

- A more sensitive method than the Ziehl-Neelsen stain, allowing easier identification of AFB using fluorescent microscopy. This technique is faster and can detect lower concentrations of bacteria.

Culture

A. Culture Media

- Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) Medium:

- A solid medium specifically designed for mycobacterial growth. The slants are incubated at 35-37°C and typically require 4-6 weeks to show growth.

- Middlebrook 7H10 and 7H11 Media:

- Liquid media that support faster growth of mycobacteria and can be used for susceptibility testing.

B. Incubation Conditions

- Cultures are incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 35-37°C for several weeks.

- CO₂ Enrichment: Some media are incubated with increased CO₂ levels to optimize the growth of M. tuberculosis.

C. Identification

- Colony Morphology: Characteristic colonies can appear rough, dry, yellowish, or buff.

- Biochemical Tests: Identification can be confirmed using various biochemical tests, such as:

- Niacin Production Test: Positive for M. tuberculosis.

- Catalase Test: Differentiates M. tuberculosis from other mycobacteria.

Molecular Methods

A. Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs)

B. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR):

-

- PCR techniques detect M. tuberculosis DNA in clinical specimens. This method is highly sensitive and can yield results within hours.

C. GeneXpert MTB/RIF

- This automated molecular diagnostic test detects TB and resistance to rifampicin, a key first-line drug.

- Advantages:

- Provides rapid results, typically within two hours.

- Particularly useful for patients with smear-negative TB or those suspected of having multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).

Serological Tests

- Various serological tests have been developed to detect antibodies against M. tuberculosis. However, these tests are not routinely recommended for diagnosing active TB due to variability in sensitivity and specificity. They may have a role in TB screening or risk assessment.

Interpretation of Results

- Microscopy

- Positive AFB Smear: Indicates the presence of M. tuberculosis, although a positive smear alone cannot confirm TB; further tests are needed.

- Negative AFB Smear: Does not exclude TB, especially in cases of extrapulmonary TB or low bacterial load.

- Culture Results

- Positive Culture: Confirmation of TB when M. tuberculosis is isolated from a clinical specimen. Cultures are considered positive when growth occurs, typically after 2-6 weeks.

- Time to Positivity: The duration until colonies are visible can vary. Rapid detection is essential for timely treatment.

- Molecular Tests

- Positive PCR Result: Indicates the presence of M. tuberculosis and can help guide therapy rapidly.

- Negative PCR Result: A negative test does not rule out TB, particularly if the bacterial load is low.

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- Performed on cultured isolates to determine drug resistance patterns. This is crucial for managing treatment, particularly in suspected MDR-TB cases.

- Methods:

- Phenotypic Testing: Involves exposing the organism to antibiotics and observing for growth inhibition.

- Molecular Testing: Can detect specific resistance genes (e.g., rpoB for rifampicin resistance).

Clinical Implications

Treatment

- TB treatment typically involves a combination of antibiotics to prevent resistance. First-line regimens usually include:

- Isoniazid

- Rifampicin

- Pyrazinamide

- Ethambutol

- Treatment duration is generally 6-9 months, depending on the type of TB and patient factors.

Follow-Up

- Patients require regular monitoring for treatment response and potential side effects.

- Follow-up may include repeat sputum examinations and imaging studies (e.g., chest X-rays) to assess the resolution of the infection.

Public Health Considerations

- TB is notifiable; healthcare providers must report cases to public health authorities.

- Effective public health strategies include contact tracing, preventive therapy for high-risk individuals, and vaccination with the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine in certain populations.

Challenges in Diagnosis

- HIV Co-Infection: Individuals with HIV have a higher risk of developing TB, and the diagnosis may be more challenging due to the immune-compromised state.

- Drug Resistance: Increasing rates of drug-resistant TB complicate diagnosis and treatment, necessitating more advanced diagnostic techniques and careful management.

Advances in TB Diagnostics

- New technologies and methodologies are continually being developed to improve the speed and accuracy of TB diagnosis:

- Point-of-Care Tests: Rapid tests that can be performed in clinical settings to provide immediate results.

- Whole Genome Sequencing: An advanced technique that can identify strains and resistance patterns, providing insights into epidemiology and treatment.