Introduction

-

Shigella is a Gram-negative, non-motile, non-spore-forming bacillus.

-

It belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae.

-

Shigella is the causative agent of shigellosis (bacillary dysentery).

-

The disease is characterized by bloody diarrhea, mucus in stool, abdominal cramps, and fever.

-

Transmission occurs through the fecal–oral route, mainly via contaminated food, water, and hands.

-

Shigella has a very low infective dose, making person-to-person spread common.

-

Humans are the only natural reservoir of Shigella.

-

The organism primarily invades the colonic mucosa, causing inflammation and ulceration.

-

Certain strains produce Shiga toxin, which contributes to severe intestinal damage.

-

Shigellosis is common in children, overcrowded areas, refugee camps, and regions with poor sanitation.

-

Shigella infection remains a significant public health concern in developing countries.

General Character

-

Genus: Shigella

-

Species:

-

Shigella dysenteriae

-

Shigella flexneri

-

Shigella boydii

-

Shigella sonnei

-

-

Family: Enterobacteriaceae

-

Gram Staining:

-

Shigella is a Gram-negative bacterium

-

Appears pink on Gram staining due to:

-

Thin peptidoglycan layer

-

Presence of an outer lipid membrane

-

-

-

Shape and Arrangement:

-

Shape: Rod-shaped (bacilli)

-

Arrangement: Usually seen as single cells, occasionally in pairs

-

-

Oxygen Requirement:

-

Facultative anaerobe

-

Can grow in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions

-

-

Motility:

-

Non-motile (absence of flagella)

-

-

Spores:

-

Non-spore forming

-

-

Capsule:

-

Non-capsulated

-

-

Habitat and Reservoir:

-

Humans are the only natural reservoir

-

Found in the intestinal tract, especially the colon

-

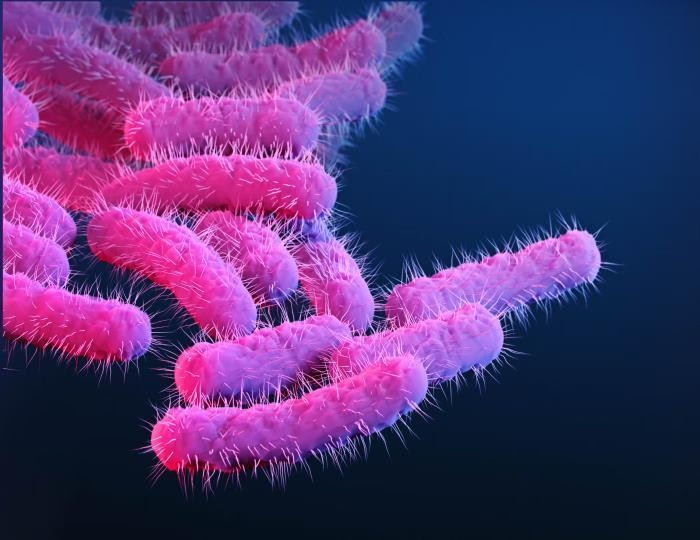

Morphology

- Shigella are small, Gram-negative bacilli.

- They are straight rod-shaped bacteria, measuring approximately 1–3 µm in length.

- Cells are usually seen singly, occasionally in pairs.

- They do not form spores.

- Capsule is absent.

Cell Wall Structure

- The cell wall consists of:

- A thin peptidoglycan layer

- An outer membrane

- The outer membrane contains lipopolysaccharides (LPS).

- LPS acts as an endotoxin and plays an important role in:

- Virulence

- Induction of inflammation

- Systemic toxicity in severe infections

Flagella

- Shigella species are non-motile.

- Flagella are absent, which helps differentiate Shigella from motile enteric bacteria like E. coli.

Special Morphological Features

- Does not show darting or swarming motility

- Shows no branching or filament formation

- Appears as pink rods on Gram staining

Cultural Characteristics

Growth Media

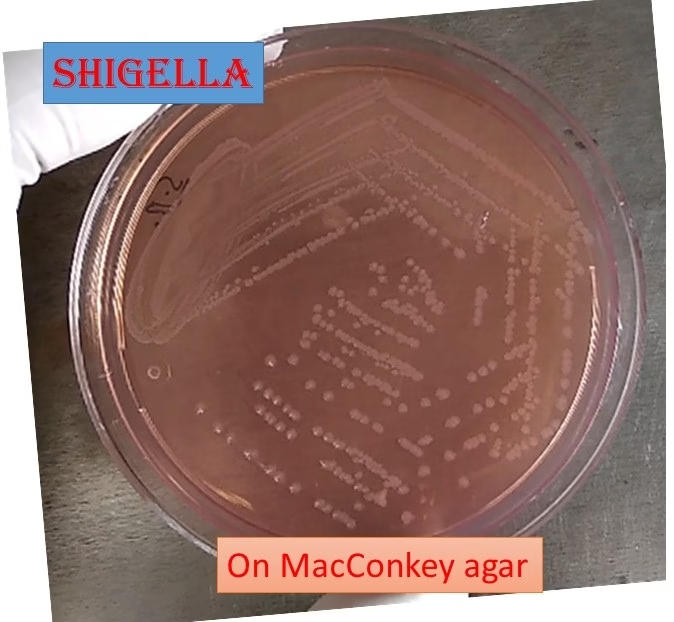

1. MacConkey Agar

-

Selective and differential medium for Gram-negative enteric bacilli

-

Shigella produces colorless (pale) colonies

-

Indicates non-lactose fermentation

-

Helps differentiate Shigella from lactose-fermenting organisms like E. coli

2. XLD Agar (Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate Agar)

-

Useful for differentiation of enteric pathogens

-

Shigella forms red colonies without black centres

-

Does not ferment xylose

-

Absence of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) production distinguishes it from Salmonella

3. Hektoen Enteric Agar

-

Highly selective medium for stool cultures

-

Shigella colonies appear green to colorless

-

Lack of sucrose and lactose fermentation

-

No black precipitate (H₂S negative)

4. Nutrient Agar

-

Growth is moderate

-

Colonies are:

-

Smooth

-

Circular

-

Convex

-

Translucent

-

Colony Appearance (General)

-

Colonies are pale or colorless on selective media

-

Reflects non-lactose fermenting nature

-

Colonies are usually small to medium-sized

-

Surface is smooth and moist

Temperature and pH Range

-

Optimal temperature: ~ 37°C

-

Growth range: 22–44°C

-

Optimal pH: 6.0–7.5

-

Growth is inhibited in highly acidic environments

Oxygen Requirement

-

Facultative anaerobe

-

Grows in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions

Diagnostic Importance

-

Non-lactose fermenting colonies on MacConkey agar raise suspicion of Shigella

-

Combined use of MacConkey, XLD, and Hektoen agar improves isolation accuracy

-

Further confirmation requires biochemical and serological tests

Biochemical Reactions

1. Catalase Test

-

Positive

-

Produces effervescence (oxygen bubbles) when hydrogen peroxide is added

-

Helps differentiate Shigella from catalase-negative organisms

2. Oxidase Test

-

Negative

-

Distinguishes Shigella from oxidase-positive organisms like Vibrio

3. Lactose Fermentation

-

Non-lactose fermenter

-

Produces colorless colonies on MacConkey agar

-

Important for differentiation from E. coli

4. Indole Production

-

Variable reaction

-

Shigella flexneri – Indole positive

-

Shigella dysenteriae – Variable

-

Shigella boydii – Variable

-

Shigella sonnei – Indole negative

-

-

Useful for species differentiation

5. Methyl Red (MR) Test

-

Positive

-

Indicates mixed acid fermentation of glucose

-

Produces stable acidic end products

6. Voges–Proskauer (VP) Test

-

Negative

-

Indicates absence of acetoin production

-

Helps differentiate Shigella from VP-positive enteric bacteria

7. Additional Biochemical Characteristics (Important)

-

Glucose fermentation: Positive (acid only, no gas)

-

Gas production: Absent

-

Urease: Negative

-

Citrate utilization: Negative

-

H₂S production: Negative (no black precipitate on XLD or HE agar)

Pathogenicity

Virulence Factors

-

Invasion Plasmid Antigens (Ipa proteins)

-

Encoded by a large virulence plasmid

-

Help bacteria invade colonic epithelial cells

-

Facilitate cell-to-cell spread

-

-

Type III Secretion System

-

Injects Ipa proteins directly into host cells

-

Enables bacterial entry and intracellular survival

-

-

Shiga Toxin (especially S. dysenteriae type 1)

-

Potent cytotoxin

-

Inhibits protein synthesis by inactivating ribosomes

-

Responsible for severe disease and complications

-

-

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

-

Acts as endotoxin

-

Triggers intense inflammation and fever

-

Mechanism of Pathogenesis

-

Ingestion

-

Infection occurs via fecal–oral route

-

Very low infective dose (10–100 organisms)

-

-

Survival in Stomach

-

Acid-resistant → survives gastric acidity

-

-

Colonization of Colon

-

Reaches large intestine

-

Attaches to M cells of Peyer’s patches

-

-

Cell Invasion

-

Penetrates epithelial cells

-

Escapes phagocytic vacuoles

-

Multiplies intracellularly

-

-

Cell-to-Cell Spread

-

Uses host actin polymerization

-

Causes extensive tissue destruction

-

-

Inflammation and Ulceration

-

Destruction of colonic mucosa

-

Formation of ulcers and exudates

-

-

Toxin Action

-

Shiga toxin causes:

-

Cell death

-

Reduced absorption

-

Increased intestinal permeability

-

-

Clinical Manifestations

-

Fever

-

Abdominal cramps

-

Tenesmus

-

Frequent stools with blood and mucus

-

Dehydration (usually mild compared to cholera)

Complications

-

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (especially with S. dysenteriae)

-

Toxic megacolon

-

Rectal prolapse (children)

-

Seizures (due to neurotoxins or fever)

Laboratory Diagnosis

1. Specimen Collection

-

Fresh stool sample is the specimen of choice

-

If stool is not available → Rectal swab

-

Sample should be collected before antibiotic therapy

-

If delay is expected, transport in Cary–Blair transport medium

2. Direct Microscopy

-

Saline wet mount:

-

Shows pus cells (neutrophils) and RBCs

-

-

Gram staining:

-

Small Gram-negative bacilli

-

-

Microscopy is suggestive but not confirmatory

3. Culture Methods

Primary Plating Media

-

MacConkey agar

-

Shigella forms colorless (non-lactose fermenting) colonies

-

-

XLD agar

-

Red colonies without black centres

-

-

Hektoen Enteric agar

-

Green or colorless colonies

-

No H₂S production

-

Enrichment Media

-

Used when bacterial load is low:

-

Selenite F broth

-

Gram-negative (GN) broth

-

-

Increases chances of isolation

4. Colony Identification

Suspected colonies are:

-

Pale / colorless

-

Small to medium sized

-

Smooth and convex

These colonies are further subjected to biochemical testing.

5. Biochemical Identification

Typical reactions of Shigella:

-

Oxidase: Negative

-

Catalase: Positive

-

Glucose: Fermented (acid only, no gas)

-

Lactose: Not fermented

-

Urease: Negative

-

Citrate: Negative

-

Indole: Variable

-

MR: Positive

-

VP: Negative

-

H₂S: Negative

6. Serological Identification

-

Slide agglutination test

-

Performed using:

-

Polyvalent and monovalent Shigella antisera

-

-

Confirms species and serogroup

-

Important in epidemiological surveillance

7. Molecular Methods

-

PCR-based assays

-

Detect virulence genes (e.g., ipaH)

-

-

High sensitivity and specificity

-

Used mainly in reference and research laboratories

8. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

-

Performed by Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method

-

Essential due to high levels of antimicrobial resistance

-

Guides appropriate treatment

Antibiotic Resistance

-

Shigella species have shown a progressive and alarming emergence of antibiotic resistance, particularly in endemic and outbreak-prone regions.

-

Resistance is more common in areas with:

-

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics

-

Poor sanitation and high transmission rates

-

Inadequate antimicrobial surveillance

-

Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Shigella

-

Multidrug-resistant strains are increasingly reported worldwide.

-

Common resistance patterns include:

-

Ampicillin

-

Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole)

-

Chloramphenicol

-

Nalidixic acid

-

-

MDR strains complicate treatment and increase the risk of treatment failure and prolonged fecal shedding.

Treatment Options in the Era of Resistance

-

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) is essential before initiating definitive therapy.

-

Empirical treatment should be guided by local resistance patterns.

-

Commonly recommended antibiotics for moderate to severe shigellosis include:

-

Azithromycin

-

Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin)

-

Third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone) in severe or pediatric cases

-

-

Rehydration therapy remains a critical component of management and should not be delayed.

Prevention

1. Hygiene Practices

-

Proper handwashing with soap and clean water is the most effective preventive measure.

-

Hands should be washed:

-

After using the toilet

-

After changing diapers

-

Before preparing or eating food

-

-

Maintaining personal and environmental hygiene is crucial.

-

Effective sanitation prevents transmission in:

-

Crowded households

-

Day-care centers

-

Schools and refugee camps

-

2. Sanitation and Safe Water

-

Use of safe and treated drinking water.

-

Proper disposal of human waste.

-

Prevention of open defecation.

-

Regular cleaning and disinfection of toilets and surfaces.

3. Food Safety

-

Consumption of freshly cooked food.

-

Avoidance of raw or undercooked foods.

-

Washing fruits and vegetables with safe water.

-

Proper storage of food to prevent contamination.

-

Maintaining hygiene during food handling and preparation.

4. Control of Person-to-Person Spread

-

Isolation of infected individuals when possible.

-

Proper disposal of contaminated diapers and materials.

-

Health education to caregivers and food handlers.

5. Vaccination

-

No licensed vaccine is currently available for Shigella.

-

Multiple vaccine candidates are under active research and clinical trials.

-

Vaccination remains a future preventive strategy, especially for children in endemic areas.

6. Public Health Measures

-

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment reduce transmission.

-

Surveillance and outbreak monitoring.

-

Health education programs focusing on hygiene and sanitation.

MCQs

1. Shigella belongs to which family?

A. Vibrionaceae

B. Enterobacteriaceae

C. Pseudomonadaceae

D. Neisseriaceae

2. Shigella is classified as:

A. Gram-positive cocci

B. Gram-negative bacilli

C. Acid-fast bacilli

D. Spirochetes

3. Which disease is caused by Shigella?

A. Cholera

B. Typhoid fever

C. Bacillary dysentery

D. Amoebiasis

4. The natural reservoir of Shigella is:

A. Animals

B. Soil

C. Humans

D. Water

5. Shigella species are:

A. Motile

B. Non-motile

C. Spore-forming

D. Acid-fast

6. The shape of Shigella is:

A. Cocci

B. Spiral

C. Rod-shaped

D. Comma-shaped

7. Shigella is a:

A. Obligate anaerobe

B. Obligate aerobe

C. Facultative anaerobe

D. Microaerophile

8. Which species produces Shiga toxin most commonly?

A. Shigella sonnei

B. Shigella flexneri

C. Shigella boydii

D. Shigella dysenteriae

9. Shigella primarily affects which part of intestine?

A. Duodenum

B. Jejunum

C. Ileum

D. Colon

10. The infective dose of Shigella is:

A. Very high

B. Moderate

C. Very low

D. Unknown

11. On MacConkey agar, Shigella forms:

A. Pink colonies

B. Yellow colonies

C. Colorless colonies

D. Mucoid colonies

12. Shigella on XLD agar produces:

A. Yellow colonies

B. Red colonies without black centre

C. Black colonies

D. Green colonies with black centre

13. Hektoen Enteric agar shows Shigella colonies as:

A. Orange

B. Black

C. Green or colorless

D. Yellow

14. Shigella ferments glucose with:

A. Acid and gas

B. Gas only

C. Acid only

D. No fermentation

15. Lactose fermentation by Shigella is:

A. Positive

B. Late positive

C. Negative

D. Variable

16. Catalase test for Shigella is:

A. Negative

B. Weakly positive

C. Positive

D. Variable

17. Oxidase test for Shigella is:

A. Positive

B. Negative

C. Variable

D. Delayed positive

18. Indole test in Shigella is:

A. Always positive

B. Always negative

C. Variable

D. Strongly positive

19. Methyl Red test for Shigella is:

A. Negative

B. Positive

C. Variable

D. Delayed

20. Voges–Proskauer test for Shigella is:

A. Positive

B. Weakly positive

C. Negative

D. Variable

21. H₂S production by Shigella is:

A. Positive

B. Strongly positive

C. Weak

D. Negative

22. Major virulence mechanism of Shigella is:

A. Enterotoxin production

B. Capsule formation

C. Invasion of colonic epithelium

D. Spore formation

23. Shigella spreads mainly by:

A. Airborne route

B. Vector bite

C. Fecal–oral route

D. Sexual transmission

24. Stool in shigellosis typically contains:

A. Only water

B. Blood and mucus

C. Fat droplets

D. Parasites

25. Specimen of choice for diagnosis is:

A. Blood

B. Urine

C. Stool

D. CSF

26. Transport medium used for stool samples is:

A. Stuart medium

B. Cary–Blair medium

C. Alkaline peptone water

D. Robertson medium

27. Definitive diagnosis of Shigella is by:

A. Microscopy

B. Culture

C. Serology only

D. Clinical features

28. Slide agglutination test is used for:

A. Antibiotic testing

B. Species identification

C. Serotyping

D. Motility detection

29. Shigella is resistant increasingly to:

A. Penicillin only

B. Ampicillin and cotrimoxazole

C. Vancomycin

D. Amphotericin B

30. Multidrug-resistant Shigella strains are:

A. Rare

B. Not reported

C. Increasing globally

D. Only laboratory artifacts

31. Drug commonly used in severe shigellosis is:

A. Penicillin

B. Azithromycin

C. Vancomycin

D. Metronidazole

32. Antibiotic susceptibility testing is:

A. Optional

B. Not required

C. Essential

D. Only for research

33. Most effective preventive measure is:

A. Vaccination

B. Antibiotic prophylaxis

C. Hand hygiene

D. Bed rest

34. Vaccine against Shigella is:

A. Widely available

B. Live attenuated

C. Under research

D. Compulsory

35. Shigella is:

A. Spore forming

B. Acid fast

C. Non-spore forming

D. Encapsulated

Answer Key

-

B

-

B

-

C

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

C

-

D

-

D

-

C

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

C

-

C

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

D

-

C

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

B

-

B

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

B

-

C

-

C

-

C

-

C